Within weeks of the start of the Second World War, a residence survey was taken across the country with the information it provided used to issue identity cards and distribute ration books. On it, we find 18-year-old Meredith still living with her parents in the tightly packed terraced streets of an industrial area in Carlisle. She is described as a factory typist. Her father is a factory warehouseman, her mother undertakes unpaid domestic duties. Her sweetheart, John (my father’s cousin), can’t be found in the survey. As members of the armed forces weren’t registered unless home on leave, we must assume he had been early to volunteer and was elsewhere on military duties.

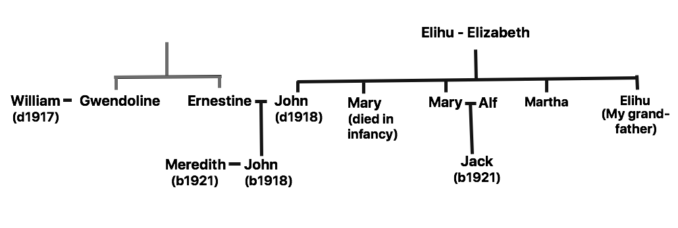

Not surprising as his own father had died through sickness as a result of wounds in the First World War and an uncle, on the other side of the family, had been killed at Ypres in August 1917, only 22 months after marrying. As a measure of the mixed fortunes of war, a cousin of the bereaved sisters was war hero William Burnell May who was awarded the Military Cross and invited to Buckingham Palace to meet the King.

A photo postcard of John in plain badgeless uniform survives in our family deed box. It’s held within a faded envelope embossed ‘W.Craig, The Studio, Thetford.’ The Norfolk town was, and still is, a military training area. Its sand dunes and low lying ground were used to practice tank manoeuvers during the First World War. In the Second War, the area available to the military was expanded, resulting in the evacuation of the nearby villages of Buckenham Tofts, Langford, Stanford, Sturston, Tottington and West Tofts.

Another similar photo shows John every inch the soldier and much padded out compared with the scrawnier youth we saw with his arm around Meredith in a previous episode. He proudly wears the distinctive cap badge of the Royal Army Service Corps.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

Up until the end of the previous century, civilian camp followers carried out the duties of the RASC. These included transport, administration, supplies and even fire fighting. In 1888 various units were consolidated into one single corps, the Army Service Corps which was awarded the Royal prefix in 1918. A despatch from Captain Slugwash reminds us RASC servicemen, it being a large and many-headed multi-tasked hydra, are more difficult to track than those of infantry regiments. Therefore there is a gap in the story, a gap punctuated by a very happy event in the spring of 1941.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

To their left, the happy couple is flanked by the best man, a 19-year-old cousin confusingly also called John (and known as Jack). Born in 1921, Jack was possibly named after John Snr who was also known as Jack. Jack’s father, Alf, husband of my great uncle and my grandfather’s sister Mary had also been in the First War. We shall return to his interesting service in a future episode.

© Always Worth Saying 2022, Going Postal

We take up the story the following year, in November 1942. Operation Torch saw the invasion of French North Africa which at the time consisted of colonies aligned to Vichy France and Germany. Torch would allow a pincer attack on Romel’s Afrika Korps in Tunisia with Montgomery and the 8th Army already advancing from Lybia to the east.

Operation Torch – North Africa 8 November 1942,

US Federal Government – Public domain

My investigation catches up with John in Algeria, east of the initial landings, only 200 miles from Tunis. Royal Navy Lieutenant Geoffrey Harold Yeldman takes up the story via a handwritten account passed to the BBC’s People’s War archive. Lt Yeldman had struck out from the Clyde on 7th/8th November 1942 on the troopship Staffordshire as part of a convoy heading to the Med. He writes,

“One night there was great excitement onboard – everyone on deck as we sailed close to Tangier, the promenade a blaze of lights, a sight we had not seen for months in the UK. Tangier, of course, was neutral territory. Soon we were off Algiers, a magnificent sight in the sunshine, the white buildings contrasting with the brown foothills of the Atlas Mountains in the distance. There had been a little firing from the French when the first party arrived but we were alongside in peace and quiet — and very hot in our ordinary naval uniform.”

In Algiers, Yeldman experienced a German air raid and a change of ships. Continuing eastwards along the coast on a converted ferry, en route the vessel came under an ineffectual attack from 2 Caproni torpedo planes before arriving at its destination.

“Early evening we were approaching Bône, the coast absolutely magnificent and the town topped by a beautiful modern church; a solitary “Spitfire” circled overhead amidst cheers from below! As we neared the berthing quay there was an eerie silence on board as everyone realised that the dockside appeared empty, hardly enough Army and Naval personnel to berth the ship. Later on, when we were in our commandeered hotel and darkness had fallen, we realised only too well why the area appeared so empty — the locals spent their nights away in the hills!”

The church in the distance still stands and will have been St Augustine’s Basilica. Bône is the French colonial name for the ancient city of Hippo, in classical times a Roman settlement and the birthplace of St Augustine.

The reason locals spent their nights in the hills was because of regular German air raids coming in from Sicily only 270 miles distant. Yeldham describes Bône as being a place of about 60,000 souls, complete with an Italian consulate containing a free public cinema showing Nazi propaganda films.

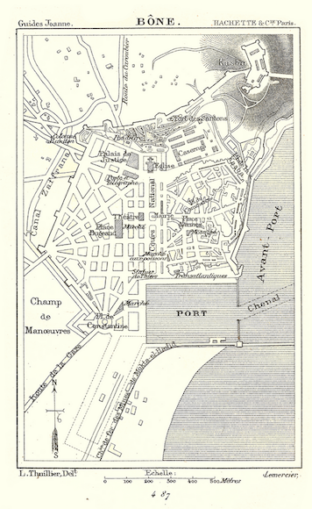

Carte de la ville de Bône en Algerie,

Louis Piesse – Public domain

Reference to the map above shows an Arab quarter tucked into the bay complete with its own mosque. Up on the hillside behind sits a fortress cum kasbah. Further inland, wide boulevards defined French colonial arrondissements and to the south can be seen a man-made harbour complete with dredged channel usefully running well out to sea. A connecting rail spur is also shown.

Annaba Bône rue Gambetta,

Unknown photographer – Public domain

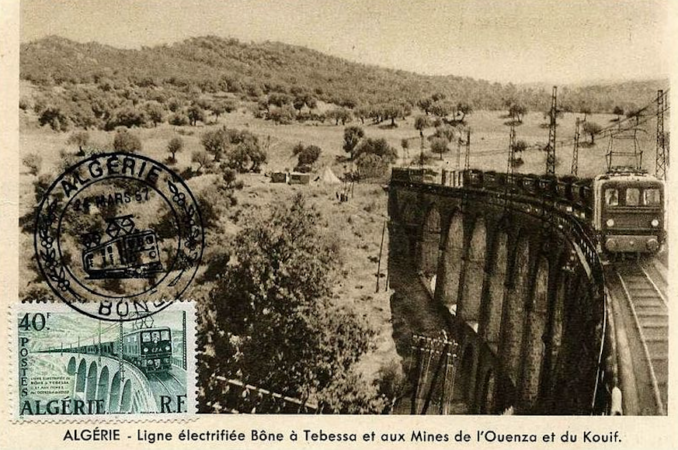

The raison d’être for the docks and railway was the iron ore deposits inland. As early as 1871 these were exploited via the Bône to Ouenza line which, even before the war, was electrified.

Bône-Ouenza line in Algeria,

Unknown photographer – Public domain

Besides the road, rails and port, John and the RASC will have been busy about the airport which lies 6 miles south of the harbour. Built on former salt flats and opened by the French in 1939, it was used by the Germans until captured by the 3rd Batallion The Parachute Regiment during the November landings. Beyond the transit facilities at Bône lay a difficult supply line heading to the front. Passing through the Atlas mountains, convoys were harried by both Axis attacks and pilfering Arabs.

Although Tunis fell to the Allies on the 13th May 1943, the grind of war continued in anticipation of the invasion of Sicily. Air raids carried on as before along with U-boat activity off the coast. Allied casualties were not to fizzle out until well into 1944.

***

In the modern-day, Bône is known as Annaba and lies within an independent Algeria fiercely achieved through yet more bloodshed. The population of the city has grown from 60,000 to half a million with another half million living in the metropolitan district.

The docks are much extended. The iron ore industry continues with the biggest steelworks in Africa, Arcelor Mittal’s El Hadjar, located just south of the city. Something of the fine Gallic boulevards survives, peeping out between garish signs and steel shutters, but they are swamped by endless concrete city blocks. Many of the outlying residential areas are reminiscent of the former colonial power’s troublesome banlieue.

A war poet might struggle. The earth is not rich, it is sand and dust. The sun is not blest but scorching. The river does not wash, it crawls through a man-made trench as if exhausted by the mountains and dreading the sea. The heavens above will remind no one of our green and temperate homeland but, inland, beyond the Route Sidi Achour and before the first twisty road rising between hardy hillside bushes, there lies a corner of a foreign field that is forever England.

According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, Bône War Cemetery contains 868 Second World War Commonwealth burials. In addition, there are 14 non-war graves, mostly of merchant seamen whose deaths were not due to war service. There is also one First World War burial transferred from Bone Communal Cemetery.

John lies close to the Cross of Remembrance. He died on 11th October 1943. After the German and Italian surrender, and entered on a casualty list as ‘died’ rather than killed or killed in action, we must assume he was lost to illness or accident. He was 25. Like his own father and so many others, he volunteered, married his sweetheart in wartime and gave his life for his country in a faraway land.

We remember them.

© Always Worth Saying 2022