© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2019

Tangled up in the Vizconce massacre investigation and having just escaped from a Filipino jail, I’m now on the run and heading south to lie low long enough to be forgotten about. I have a letter of introduction for a distant and remote contact living in a distant and remote población in a province that I’ve never heard of and which, I suspect, has troubled neither map nor atlas. So much the better. For a while God, the Pope, the Queen, England and ninety-nine point nine recurring percent of the population of the Philippines will have to manage as best they can without me.

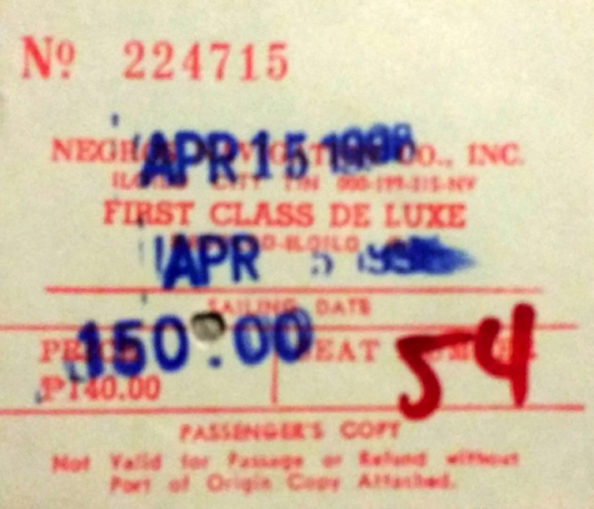

Any fool can be uncomfortable, especially on a South East Asian ferry during the typhoon season. Stowage and cabin classes are basic and crowded so I’m in Premier Delux, laughingly incognito by being the only passenger there, the only white man on board, and the only one of the thousands on the ferry dressed in silk, cotton, panama hat and monogrammed crocodile skin shoes. All my worldly goods, including both of my passports, are safely stowed in my blue Berghaus pack. Just to put the suspicion-o-meter in the red zone, I’m travelling on black market ID that makes me out to be a Caloocan City donkey breeder licensed to drive, Filipino style, anything capable of movement.

Which is no great achievement, given that local road conditions include children too small to reach the pedals operating them by having wooden blocks attached to their feet. Tyres lack rubber (let alone tread) and, speedometers being a pointless optional extra, dashboards are a blank sheet of metal, bereft of dials. One almost feels safer on this ancient, listing Star Ferry pointed towards a typhoon.

With an almost admirable resolution, the Santa Anna Navigation & Steam Packet Company Limited play the same safety video in Premier Delux class, no matter what. Passengers have been known to be praying to their ancestors, the vessel pitching perilously close to the vertical, the swell threatening to touch the sky, while a pretty girl (fortunately for herself, land and studio bound) announces from a grainy TV screen,

‘Welcome to the Santa Anna Navigation, the weather is good and the crossing is calm.’

I doze through the lifebelt drill. Regular readers will recall that there are never enough lifebelts or spaces in the lifeboats. Slightly older travelling gentlemen have the lowest priority (rightly) behind women, children, younger men and men with families. If anything terrible happens during the passage, I am certain to die, either by drowning or by being eaten by sharks.

At least I am alone, in relative luxury, and have nothing to do but sit (I mistakenly assume). It was the local custom to play violent videos, for the relaxation and peace of mind of valued customers, during journeys. The more violent the better. Extra intersessions were granted by St Christopher himself (as the patron saint of travellers) if they involved transport catastrophes such as ferry sinkings, hijackings or piracy.

Again, I mistakenly thought I was getting off lightly by sitting through an English Language French film dubbed into the local national language. A tale of a professional gentleman living in the big city and a touching relationship with his twelve-year old daughter. Unfortunately, his profession was hitman and the twelve-year old wasn’t his daughter. Very French. There unfolded a story of rage filled murder and revenge, with a professional gunman hunting one who’d escaped the law. Tempted to ask the captain to stop this minute, so I can throw myself back into the comfort and safety of the nearest Filipino jail, I am disturbed by a steward.

‘Excuse me sir, you are wanted on deck.’

‘Really?’

Beside the deck railings, outside the entrance to DeLux, stood a diminutive lady and a young but taller girl. They have a heavy case each. The girl looks gangly and weak. In patches her flesh is raw, exposed by hanging, dead skin. The lady introduces herself. She says that she knows me. Presumably in the broadest sense, of realising me to be a travelling foreigner. She has a relative in Chiswick, West London, and another in Golborne, Lancashire. Quite.

© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2019

She has prayed to God and I am His answer. A web of necessities dictates that the lady and young girl must separate. The girl must have a companion and, owing to a medical condition, would benefit from a charitable upgrade to DeLux class.

I look to the steward for advice,

‘Your choice sir.’

The girl is called Joanna. We sit together, in the otherwise deserted DeLux lounge, watching the blood and guts on the little screen.

The next time we were disturbed was after the ferry had come to an unscheduled halt, in a secluded bay, apparently because of ‘mechanical problema’. If my journey was urgent it was suggested I might consider continuing by land. Myself, Joanna and about two dozen other impatient passengers are disembarked. Joanna makes no complaints, despite being in obvious pain because of the moist, salty sea air about her poorly skin.

A larger ferry was also approaching, decrepit and listing, packed with tiny faces along the gunnels. I felt uncomfortably hot. Then a remarkable thing happened, the locals took a dislike to us and started pelting us with shells. Not the artillery type, but sea shells, some of them as big as your fist, one or two as big as a lobster. As usual, I stood there like an idiot, doing nothing, pretending to be invisible, until Joanna squeezed my arm.

© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2019

We knocked on the side of a tin hut and offered a startled barangayeno a hundred Peso to use the toilet. They didn’t have one but, for twenty Pesos, would introduce us to a neighbour who did. We snook next door and, after a comfort break, slipped out of the back way by removing part of a corrugated metal wall. Not only were we refreshed but we were armed with directions to a row of parked busses. Decrepit. Rusting. Lurching on their springs, ideal for this terrain.

Joanna exchanged words in the local dialect and we were pointed to a coach whose aircon consisted of broken windows crisscrossed with metal bars. The conductor promised that we would be comfortable. The afternoon would cool as the super cyclone approached.

‘Super cyclone?’

‘Why do you think the ferries are coming in? You don’t think anyone ever comes here do you, Joe?’

The roof being already full, we stowed our luggage underneath the coach. We headed south, just before the super cyclone’s front. Ahead, the sky was bight and blue, behind grey and darkness chased us. Occasionally, the first rainclouds would splatter the tin roof’s luggage, but never for long. The driver always pulled ahead, deeper into a vista of a world disappearing.

Beside us were paddies and patches of scruffy land. In the near distance, hills were covered in a canopy of palm and hardwood trees, with only an occasional scratched clearing. Passing through small hap hazard barangays and one street poblacións, children and emaciated dogs watched from the edges of badly made up roads. Away from the towns, little cemeteries of above ground concrete casks, stood guard on the road side. The dead protected by carvings of angels and saints, the living protected from the restless dead by cloves of garlic pinned about the holy statues. Ominously, a water buffalo hauled at a wooden yoke pulley, hoisting a mobile phone mast onto a rough concrete base.

Unfortunately, I was viewing the panorama from the back seat, to avoid a child sat at the front throwing fits. We bounced our way south. I ached all over and was beginning to feel as though I’d run a marathon, after a game of rugby, for the Celtic XV during a particularly bad-tempered match (away at the Rangers XV). The other passengers laughed as my head hit the ceiling, Joanna laughed the loudest.

Consumer advice. This sounds ridiculous but, somehow, find a structural engineer (or three) to survey the bus, and it’s route, before you commit to travel. You have no idea how uncomfortable it can be. At the very least promise me that you’ll sit on a middle bench. Deal?

Beyond the laughter, Joanna was shy, her English not great. She whispered that her ambition was to be a nurse, or maybe even a doctor (if God willed it), perhaps a nun. In whatever case, presumably because of her own condition, she would like to spend her life making a better world by helping the sick.

‘Perhaps, one day, I might help make utopia?’

I reciprocated, telling her that, as her previous companion had noticed, I was an English travelling gentleman engaged in derring-do. I confided that the new technology was catching us out. We were being replaced and had less and less to do. Joanna looked bored. However, one or two in my section, including her humble chaperone, were wizzes with the IT, keeping ourselves relevant for a bit longer. She‘d gone glassy eyed. But we were under-employed and were used as dog’s bodies in-between assignments.

I’d been seconded from Hong Kong to be ‘about the place’ during the Philippine elections and then ‘set something up on the business and money side of things’, as Honkers was being handed over to the Chinese, Taiwan was controversial and Guam and Singapore were a bit distant. She was fast asleep, her sore skin resting on the back of the rusty bench in front of us.

Colleagues were all self-employed contractors, were paid too much and allowed a few little investments on the side, which is why the Embassy and anybody in a uniform with a Union Jack on it hated us. But we didn’t get proper pensions, which was an issue. I was beginning to bore myself. People sat nearby were making excuses and squeezing in beside the fit throwing child.

I had my own perfume range. No matter what it said on the bottle, it was called ‘Keeping in Touch’. My contact details were on the bottom of each bottle, on a sticky label. She must remind me; I would give her the best one from my pack.

© Always Worth Saying, Going Postal 2019

It was getting dark by the time the weather caught up with us and overcast cloud with sheets of rain spoiled our view. The day ended too quickly. There was a sudden warning-less dusk and then pitch black. Somehow, the driver continued to negotiate the road, going faster rather than slower. There were no stars, never mind a moon. Scattered lights outside congealed, other vehicles surrounded us. We had arrived in a city, my stop and Joanna’s destination. Alighting, I couldn’t stand up. The firm ground caused me to stumble. I linked arms with Joanna, while we looked along the bottom of the bus for our sodden, muddied luggage.

There we had to part as I must hurry to the docks from where I had to take another, overnight, ferry. Joanna asked me for a blessing. I pressed the back of my hand to her forehead, in the local manner, and whispered a prayer,

‘Lord, bless Joanna, and allow me to ask her a favour.’

By the time the sun had risen again, I was already on the wide concrete roads of a neighbouring island following a flat, cane filled fringe between far inaccessible mountains and turquoise sea. Giant Hino trucks thundered past, loaded with sugar cane. Boys sat on top of, or strode, the shifting loads. Out in the fields there were rows of croppers and little narrow-gauge engines, on temporary rails, puffing black smoke to the sky as they pulled trolleys of harvest.

Further south, where cliffs suddenly surprised the mountains to the sea, progress was slower. Our FX had to zig-zag around both big potholes and even bigger potholes. The driver couldn’t keep ahead of the rains and had to contend with gulley torrents of water cascading down the road. At one bend, we had to stop and, for a few Pesos, take shelter in a native’s nippa hut. A respite in the weather encouraged us to set off again, this time dropping towards quarries. The roads were soaked in a pale, lime yellow, paddy killing flood.

The driver announced he must stop for the night at the next settlement. Fortuitously this was my destination. About half an hour later, the bedraggled passengers traipsed under the canopy and into the shop at ‘Christie’s Corner Property’, beside Rizal Square, nicely in the middle of nowhere, the address on my letter of introduction.

I invited myself upstairs, waving the letter, to a loud and raucous welcome from a kitchen full of aunties. The one with thick-thick glasses prepared fish for supper. The jungle drums had been beating, the shortwave cackling, I wasn’t unexpected. A reputation proceeded me, not because of any derring-do, but because of my disgusting and inexplicable habit of throwing fish’s heads to the cat and just eating the body. Yuk.

Another aunt, the head of the family in this place, sat me down with some rice and a spoon, directly under a faded pencil drawing on the wall. Above me, eight brothers were depicted in a line, in order of age not honour, looking out over the family that they had established generations ago. They were introduced to me as Dong, Fong, Long, Tong, Bong, Hong, Gerald and Mark, which I took to be some kind of a joke, but at least it made them easy to remember.

Part of the property was a migrant worker’s hostel and, after supper, there was a bunk for me there. Settling to sleep, purely out of self-interest, I begged God for a safe journey for Joanna and pleaded that He should insist my asked for favour upon her.

To be Continued…..

© Always Worth Saying 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player