In 1965 Yulian Semyonov wrote an espionage thriller, No Passport Required. It received good reviews and millions of readers. More importantly, in 1968, it came to the attention of Yuri Andropov, the recently appointed Chairman of the KGB, who suggested a meeting. By this time, Semyonov had already published the second in the series with Vsevolod Vladimirov, the young Cheka officer, as the main character. Andropov was extremely attracted to the genre and the character, envisioning a KGB that portrayed itself as dependent more on wit, intellect and a moral and philosophical purity of purpose than cold-blooded assassinations or ruthless political purges in Soviet satellites—which aligned well with Vladimirov’s character (Andropov’s romantic visions were obviously somewhat detached from the reality of KGB operations on the ground, but let’s not digress…).

I don’t want to give the plot away, so I will discuss what I picked up from the episode and why it’s still resonant.

Introduction

Seventeen Moments of Spring is often filed away as a Cold War artifact, but it rewards a very different kind of attention: not as a story to be recounted, but as an experience of craft and psychology to be observed. What struck me on watching the first episode was not the plot—but the extraordinary subtlety of its craft: the deliberate pacing, the quiet confidence of its direction, and the way it exposes the psychological architecture of a system built on power, fear, and performance.

The series unfolds in an environment where propaganda stops being a tool and becomes the organising principle of reality itself. Military objectives exist not to win a war but to sustain the illusion of coherence; strategy bends to narrative, not the other way around. The result is a world where truth is provisional, and the institutions enforcing that ‘truth’ appear increasingly fragile—an edifice creaking under its own weight.

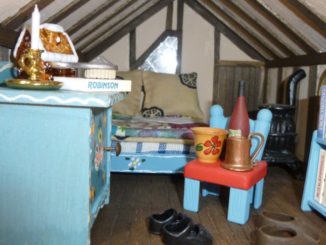

Within this landscape, questions of identity and control become central. Every character is performing a role—sometimes willingly, often not—and the tension lies in how thin the line is between the mask and the self. Stirlitz’s life, built on layers of constructed identity, is revealed in small domestic details: his remark that his maid enjoys ‘the luxury of not needing to know the exact time’ captures the strain of perpetual vigilance, the difference between a life that can flow and a life that must be measured. In such moments, the series shows how power and performance colonise even the most ordinary experiences.

Opening Scene

We are introduced to a handsome man in his mid-30s in a forest clearing somewhere near Potsdam, in company with an older lady; an attractive sedan is parked in the background on a small road. The conversation is slow, trivial and punctuated by long silences. The music is gentle and incidental, no theme emerges and no hint of what you are getting into. The angle of shot is not intimate but not distant; you are encouraged to observe without being observed. It pricks the curiosity without grabbing attention.

Interrogations: When the State Cannot Control What It Cannot Comprehend

What stayed with me long after the first episode was not the espionage mechanics but the interrogations—those uncanny, airless rooms where two worlds meet but cannot understand one another. The scientist and the pastor are not imprisoned for their actions; they are held because the system cannot classify the ideas they represent. Their motivations are rooted in forms of purpose that lie outside the regime’s logic: curiosity for truth, service to others, belief shaped by community and conscience. These are relational, inwardly grounded impulses, not the fear‑and‑reward calculus by which the state expects all behaviour to be governed.

This is why the interrogators appear both confident and unsettled. They ask the same questions in different configurations—Who directed you? Who funded you? What did you hope to gain?—because they only possess questions shaped by suspicion, hierarchy, and material incentives. When faced with people who act from convictions that cannot be bought, threatened, or repurposed, the machinery of power stalls. The threat is not disobedience but unclassifiable meaning.

The series captures this with restraint. There are no dramatics—just the quiet tension of two incompatible worldviews. The interrogators are bureaucrats trying to force the intangible into paperwork. The prisoners have done nothing except exist in a way that makes no sense inside a paranoiac framework. The result is a distilled portrait of authoritarian anxiety: a regime that fears not actions but inner life.

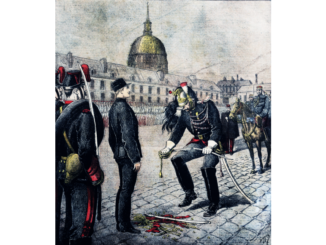

A Country Is Its People: The Futility of Sacrifice in a War Already Lost

Another theme lands with stark clarity: the dying of the young and the old in a war that can no longer be won. If a country is its people—its living inheritance of culture, memory, and possibility—what does it mean when those people are sacrificed for objectives that no longer have meaning?

This is more than an anti‑war sentiment; it is a question of identity and purpose. A nation is not its borders or its slogans; it is the shared life of its citizens—their language, their ordinary days. When the state continues to demand lives after victory or meaning has evaporated, the war becomes a form of self‑harm. Military objectives no longer serve the nation; the nation serves the objectives, even when those objectives are hollow.

This is the crumbling edifice at the heart of propaganda‑driven systems. When narratives no longer align with reality, the first casualties are often the most irreplaceable: the people who constitute the country’s very meaning. The series invites us to ask—quietly, insistently—what any state is fighting for if the cost is the erosion of the human community it claims to defend.

Conclusion

Taken together, these threads—surveillance of the self, interrogations that expose the limits of power, and the tragic arithmetic of sacrifice—reveal Seventeen Moments of Spring as a meditation on systems and selves rather than a tale of intrigue. It shows us how propaganda tries to harden into reality, how identity thins under the pressure of performance, and how control falters when it meets ideas that do not grow in the soil of fear or reward. And it poses the most human question of all: what remains of a country when its people are gone?

As Mikhail Bulgakov reminds us, ‘Manuscripts don’t burn.’ Ideas, memories, and conscience outlast the apparatus that seeks to control them. In the end, that may be the quiet hope the series offers: that the meanings we live by are more durable than the systems that try to contain them.

© Roger Mellie 2026