“Malka and Shlomo in the Secret Shtetl” was inspired by a story which circulated within dissidents circles when I was a student in Moscow in the early 1980s: several villages in Siberia were so remote and cut off from the world, I was told, that their inhabitants did not know that there had been a revolution in 1917 and still believed Russia lived under Czarist rule. Needless to say, the Regime’s henchmen had been actively scouring Siberia for decades in order to discover those villages and enlighten the unfortunate villagers about Vladimir Ilyich (minus the pox) and the gulag right down the road. Let me reassure my tender-hearted readers immediately: they were never found.

Of course, my liberal friends in the West scoffed at that story. It was a well-known fact, they said, that Soviet dissidents were fascists and complete idiots, especially those who were academicians or Nobel Prize winners, at a time when a Nobel Prize was still hard to win. Liberals have no idea of the immensity, extreme weather and emptiness of Siberia. They would never travel to a God-forsaken place where the shortage of tofu is dire!

Even though I was a liberal at the time, I thought the story was likely to be true. I had been shown hilarious Pravda articles from the Seventies in which the writers expressed genuine pity for the Siberian villagers and hoped that, for their own good, they would soon be found, the dissidents who had told it to me were people I loved and admired and, never having liked tofu, I had actually travelled to Siberia. I knew what it felt like to look out of a train window and not see a trace of human life for eight hours or more.

Now that life in the Wagnerian Onion under the psychotic leadership of Adolfa Garbitsch is slightly less free than that in Russia in the 1980s, those Siberian villages keep coming back to me. What if, I ask myself, there were and had always been places granted special protection from predatory regimes? I am not religious, but most of my dissident friends were. In those days, many brave Russians were put under house arrest for the crime of going to church or the synagogue. They believed that God played no small part in keeping the Siberian villagers safe from the crooked wonders of communism and were not ashamed to confess that they envied their blissful ignorance.

I suspect the Politburo, if it still existed, would also envy (and possibly copy) the absurdity of Wagnerian Onion laws and regulations. Two years ago, they broke my dentist’s heart when she retired. In 1974, she had bought her surgery, a tiny standalone house in Paris with its own garden, from an elderly dentist who had worked there since 1937, and had always hoped that after she retired she could in her turn let or sell it to a young dentist. Unfortunately, Wagnerian Onion dentist surgeries regulations demanded that she spend 11,000 Euros on stupid and useless “improvements” which would have not only disfigured the little house, but also ruined my dentist, a widow with three children and seven grandchildren. As a result, a dentist surgery in continuous operation for eighty years is now a luvvie restaurant which serves such delights as quinoa bake and carrot smoothie.

My friend P. who is ghey and extremely conservative was yet another victim of the Wagnerian Onion. His warm and friendly traditional French restaurant, the last one in the quarter, offered no fewer than twenty sorts of omelettes. One day, he received a letter from Wagnerian Onion health inspectors ordering him to use egg powder from now on, fresh eggs being apparently unhygienic and a health hazard. If he did not comply, he would be fined and his restaurant closed down. Later, when the smoking ban came into force, P. lost two-thirds of his regulars. Then one evening at 6 o’clock, an enricher he did not know from Adam walked into his restaurant and enriched him so generously with a knife that P. had to spend four weeks in hospital and take early retirement. The enricher, who lived here illegally, was given a suspended prison sentence and a fine which he was under no obligation to pay since he had never worked. Strange as it may sound, deporting that generous ghey lover was never considered. Thanks to the Wagnerian Onion, the last traditional French restaurant in the quarter is now a ghastly vegan canteen run by strangers to soap, one of whom threatened to set fire to the local supermarket two weeks ago because they had run out of sweet potatoes.

Dear readers, I have wound you up long enough. Although the second part of my story is true, the first part is not. The Siberian villages were found. They were found by the right people. Friends of mine, now dead, who were political prisoners in the early Fifties were sent out to cut timber on March 4, 1953. Caught in a snow storm, they stumbled upon a group of hamlets. The villagers listened attentively to what they had to say, then treated them to a feast. After the political prisoners had returned to the camp, the Siberian villagers made sure they would never be found again.

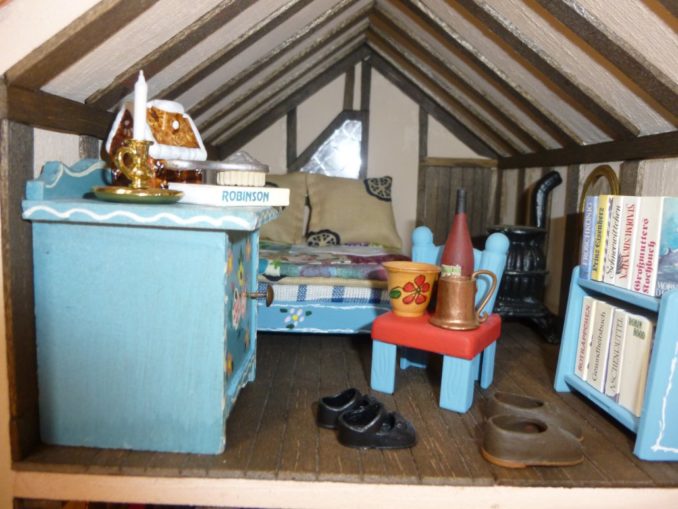

© text & pictures Doxie 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file