© Colin Cross, Going Postal 2025

It’s the waiting that gets to you. I’d arrived, as requested, at 7am and was escorted to a curtained cubicle. The people looking after me, although my needs were minimal at this time, were all very professional and went about their business in an efficient manner. It boded well, at least to my mind, for what was to follow. I had my BP taken, gave some blood for testing and had an iodine swab (for possible reaction) and answered some a few questions, more than once, before having a large blue arrow painted on my left thigh, pointing upwards towards my groin. This, I was told by the bubbly young lady that did it, was to make sure “they” didn’t “do the wrong one”. By 10.30 the time was starting to drag and it was clear that, although I was third on the list, things weren’t going quite to plan. There’d been a bad accident on the M6 and the knock on was to directly impact me. Once you’re behind the curtain, unless you’re needed for something specific, you become invisible to those on the other side, but you can still hear them gossiping about their colleagues, who said what about who, who didn’t want be on shift with a particular person just and how bad their particular lot is. Very British!

© Colin Cross, Going Postal 2025

In the week where we learn that the NHS has spent IRO £1.4billion to mitigate “klimate khange” within the organisation, without having any positive effect whatsoever (if such a thing were to be possible), it’s comforting to know that this window at the hospital, first photographed by me in January 2025, remains in much the same state as it did ten months ago. Maybe the maintenance budget got diverted to the klimate budget? I know a man who could sort this out in a couple of days and it wouldn’t cost them the earth. Priorities, eh?

© Colin Cross, Going Postal 2025

I eventually “went down” six and a half hours after I arrived at the hospital. It’d been a long morning. I had an epidural and some sedation, both the anesthetist and the senior theatre nurse assisting him were very professional and managed to allay whatever concerns I had. I have to admit that the long wait had stretched my nerves a bit. With my vitals checked again I was wheeled into the large operating theatre, not really knowing what to expect. I was totally numb from the waist down and very drowsy.

© Colin Cross, Going Postal 2025

I was woken by the sound of hammering. I couldn’t feel a thing, although I was aware that the hammering had something to do with me. High as a kite, I attempted to remove my oxygen mask, but both the anesthetist and senior nurse were there to quietly, if firmly, keep me calm. I amused myself by looking at the monitors and noticing (by touch) that a certain part of mt body was swollen to a size I would have considered impossible if I’d been told about it. Needless to say, that particular “side effect” was very short live and by 3.30 pm I was sewn and stapled back together and in recovery. Everything, or so I was told, had gone swimmingly well and all concerned were happy with both the outcome and the time it had taken.

© Colin Cross, Going Postal 2025

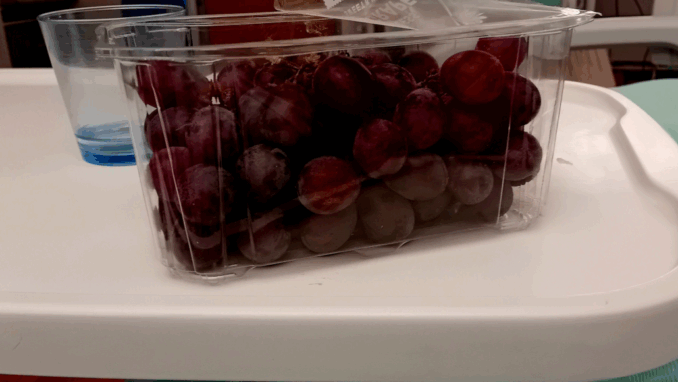

Up on the ward by 5pm and the first of my meals arrived. For those of you ensconced below the line that runs from south of the wash to the Bristol Channel, a bowl of lukewarm soup (edible enough) followed by a plateful of gravy smothered veg accompanying a piece of brick like chicken breast is just what Northern folk need to build them up following hip replacement surgery. I ate the soup, a bite of the chicken and some of the oven finished sliced potatoes, which were very nice. The apple sponge and custard, another northern classic, which followed went back to where it came from, less the apple, which I thought might make up for one of my five a day. My request for a glass of beetroot juice or a mug of nettle tea was met with blank stares and eye rolling. I remembered, as high as I still was (oramorph had been taken by this time) that my “self help” diet had me marked down, in NHS circles as “one of them”. The grapes, thoughtfully provided by my eldest daughter were very welcome. I was still numb from the waist down so the planned physio session was shelved for the day and I steeled myself for what I expected to be a night of pain, discomfort, opioid induced somnolence and urinating into cardboard bottles. I’d made myself a promise that, no matter what, a catheter wasn’t happening.

The night was interesting, liberal doses of codeine and paracetamol were administered at 6pm, with oral morphine at 8 and this continued regularly throughout the night. The banter with the staff was, for the most part, quite excellent. One of my fellow patients, (all three of them had had a new knee fitted) claimed to be in perpetual agony. The pain medication wasn’t working for him and he moaned most of the night, only easing his complaining down when the morphine came round. Sleep, as you can imagine, was at a premium. One of the other fellows had insisted on a catheter being fitted, as he couldn’t “perform” into a bottle, but he was having problems with it and his regularly delivered staccato “ouches” made a not unpleasant (to my drug addled brain) counterpoint to the more guttural groans emanating from the other side of the room. Before dawn, after I’d exchanged some further pleasantries with the lovely duty nursing aid as she’d waited for me to use a “bottle” the “moaner” said “you fancy yourself a bit of a ladies man, don’t you”? Indeed I do, I replied. The genuine laughter from the nursing aid, who I like to think had appreciated a little bit of light hearted joshing as she’d toiled through her shift was enough to forestall any further conversation on the subject. The porridge was nice and the banana (a fruit which I generally have something of an aversion to) was a necessary evil.

Day two began, the night shift changed to the day shift and the two lead nurses who took over were equally as efficient as the previous team, although the nursing assistant was a little less receptive to my “flarching”, I guess she’d seen it all before. Both the “ouching” & the moaning continued apace, with the fellow opposite now calling for assistance every few minutes, or so it seemed. I got the impression that he quite liked being a patient and he was certainly making noises about not wanting to be discharged, but I suppose it’s understandable. I listened to music, insisted I be allowed to walk to the toilet (I’d had enough of bottles) and began to learn how to use my crutches with the aid of a physiotherapist who seemed as keen to get me out of bed as I was to get moving. The place bustled and it wasn’t, apart from the fact that I was in hospital, at all unpleasant. The rest of the day passed almost uneventfully, I continued to force myself to move and the staff were more than happy to help me to do so. I was beginning to understand what “patient led” recovery was all about.

© Colin Cross, Going Postal 2025

The staff, although mostly British and “northern” were a mixed bunch racially. This made not a jot of difference to me, folk are folk is my mantra, but a fellow patient took what I though was a bit of a different tack. I wasn’t the only one who noticed, either. Whenever one of the local staff spoke to him, he replied as any person would, but when any of the female staff from other parts of the world (there were Indian, African, Filipino and East Asians on the ward) spoke to him, he always asked them to repeat what they’d said, implying that he hadn’t understood them, when it was clear to everyone else that what they’d said was perfectly intelligible. I found this disappointing, rude and (maybe) even a bit racist. We all know that the NHS is badly managed and has a great many problems, BUT the staff on the ground (at least to my mind) and from my experience (this time around) couldn’t have been more helpful, patient and understanding of all of us. To be honest, it left a bit of a bitter taste in my mouth and I didn’t speak to him much after that. I won’t bore my loyal reader with night two (much the same as night one) and day three, which saw me out of bed, dressed and being taught to negotiate a set of stairs by a jolly, long serving physiotherapist lead who’d clearly seen and done it all and who was taking no nonsense from any of us, especially the moaner, the “oucher” and the “Scouser” with the hearing problem. I was first to be discharged, but not before my canula was removed resulting in my bleeding like a stuck pig, probably due to the blood thinners, which caused a mild if short lived panic and I was glad to leave. I’d had a couple of visits from my daughter and we’d discussed the interactions I’d had. “Know what dad”? she said to me as she escorted my wheelchair down to the lobby, “you’re right, there really is nowt so queer as folk.”

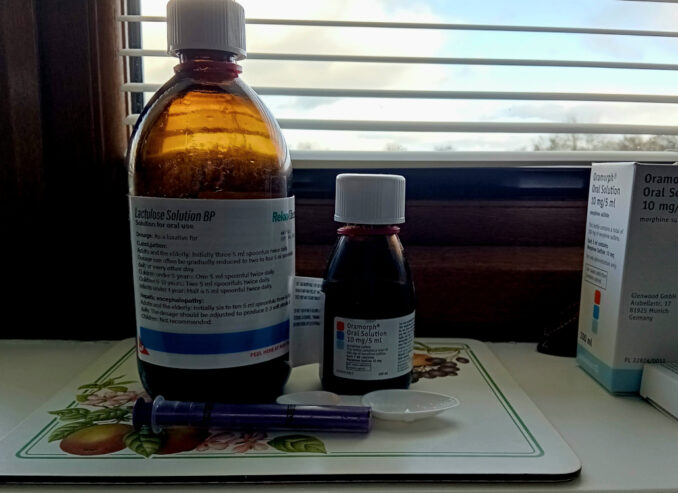

The big bottle of laxative and it’s smaller cousin, the Oramorph? Let’s just say that both were needed over the days following my discharge, the laxative a great deal more than the morphine. The relief, after six days of increasing discomfort was palpable, which is probably more information than needs to be imparted, but I’m glad that bit’s over and we can start moving forwards towards happier, less painful green-housing and, who knows, maybe even the odd fell walk or two.

© Colin Cross 2025