Apologies for last week’s Railway Review, which was far too populist. An article on a mineral railway in Northern Brazil is exactly the type of thing you might read about in a 1960s edition of National Geographic while in the waiting room of a West Country dentist. Nowhere near niche enough for the discerning and well-travelled Puffin.

I have tried harder this time. Still in South America, we shall strike out in search of the street cars of Paramaribo, in another, no doubt fruitless, attempt to find somewhere that no Puffin (other than staff) has ever been to. I’m afraid I can’t find my photos. Did I lend them to the Voorschoten Ladies’ Branch of the Dr W.J. van Blommestein Appreciation Society all those years ago and never get them back?

With no intention of ever returning, we shall rely upon Street View. Or rather, we won’t, as, in a good sign for those in search of the remote, the Google car has ventured that far not. Firstly, where is Paramaribo? Eagle-eared readers will recall Hazel Irvine having three attempts at the pronunciation (and still getting it wrong) while commentating on the Paris Olympic parade of nations along the Seine during the opening ceremony of last year’s Games.

I amazed family and stunned friends by correcting her first time. Pronounced Pa-ram-ah-ree-bo, this is the capital of Suriname. The smallest country in South America sits at the head of the Suriname River as it meets the Caribbean, 400 miles north-northwest of last week’s starting point of Serra do Navio.

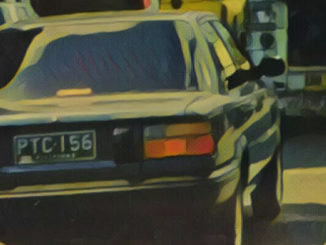

Unfortunately, the railway lines thereabouts have been closed for decades and blitzed by an ever-expanding city — now with a population touching a quarter of a million. However, I happen to have an old street map dated 1916–1917 which contains sufficient surviving landmarks to match with aerial photography from Google Earth to allow for the following effort:

© Google Maps 2025, Google licence

The yellow line leads to the northern terminal of the 173 km long Paramaribo to Dam am Sara Creek railway. According to an old timetable, the terminus was at Villantsplein. A low line speed and a relatively short wheelbase on the carriages allowed for a tight curve to the dockside. Close inspection shows that the place name survives, but the original station is gone. Back in the day, it looked like this:

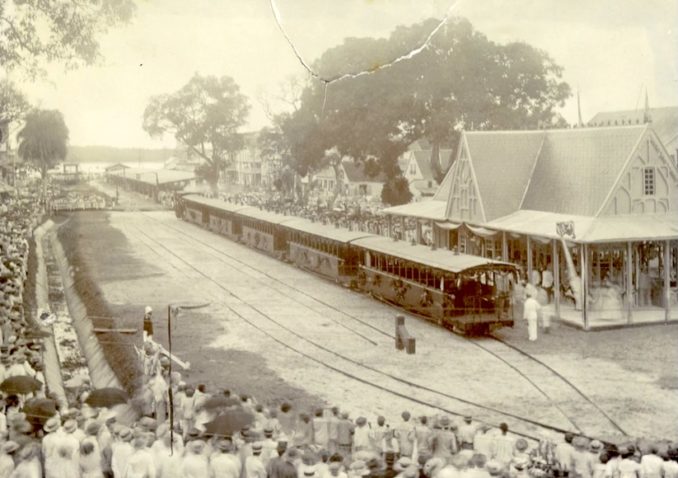

Gezicht op treinstel,

Eugen Klein – Public domain

The above shows a view of a train, station building and a large crowd at Vaillantsplein for the Lawaspoorweg opening. The day being March 28, 1905, the date of the first ride of the train. No need for platforms! Yes, all is in Dutch, as Suriname was formerly the Netherlands’ colony of Dutch Guiana, sandwiched between the French and British Guianas on the north coast of South America.

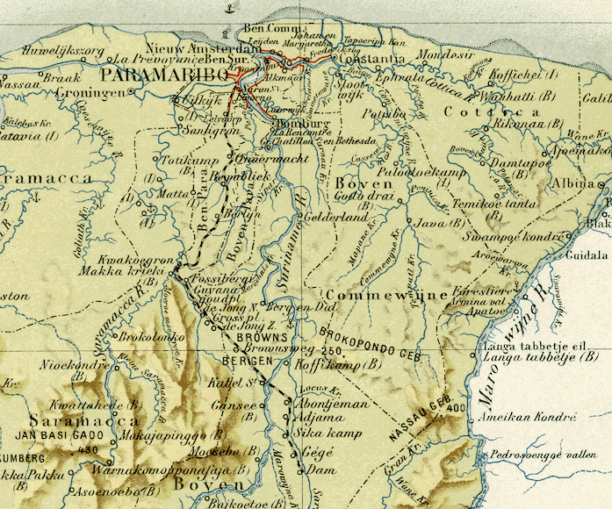

As every Puffin knows, spoor means ‘track’ and weg means ‘way’, but why was the new railway called the Lawa Trackway rather than the Paramaribo to Dam? Because the intended destination was the Lawa River, which provides a border between the Dutch and French Guianas and which was hoped to be rich in deposits of gold.

Encyclopaedie van Nederlandsch West-Indië. Suriname,

Herman Benjamins – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

The country’s first railway was built in the late 1890s on the other side of the Suriname River to Paramaribo and served the sugar cane industry around Marienburg. The first public railway opened in 1903 and ran from Paramaribo Vaillantsplein to Lelydorp at kilometre post 13. By 1905 the line had been extended to Republiek, at 41 km, hence the grand opening pictured above.

In 1912 the line reached its furthest extent at SaraKreek, 137 km by rail from the capital. Plans for a further 213 km of track to the Lawa River were abandoned when gold prospecting in the area yielded disappointing results. Not to worry, there were other gold deposits along the route as well as an abundance of bauxite, which is used in the production of aluminium.

An early timetable describes one weekly passenger service in each direction, named as the Goldfields Train, in the down direction this left Villantsplein at 7 a.m. and after 14 timetabled intermediate stops (not including request stops) it terminated at Dam 10 hours and 35 minutes later. A stately average of 16 km an hour (10 mph). However, as we shall see, there is a reason.

Rounding the tight corner leading from the Paramaribo terminus takes us to the waterfront of the Suriname River, where work is pictured being done on the construction of the railway.

Stadsgezicht in Suriname met spooraanleg,

Wesenhagen Family – Public domain

According to my street map, we look towards the main police station. Behind us lie the Pump Station of the Fire Department, the Ice Plant and the Gas Plant. In the modern day, just off-screen to the top right of our aerial photo, is an oil terminal. Since heavily modernised, on the old map it is called the Gov Petroleum Cracking Plant.

After that is the container, which sits on top of what was the Beekhuizen railroad depot and workshops of the Lawa Railway (a nearby creek on the old street map gives away the location). From there, the line took a sharp turn to the west and headed inland and away, for the time being, from the river.

According to what I can see from the satellite imagery, there is nothing left of the tracks. We resume the search at the 30 km mark at a place called Onverwacht. This had its own station, but then so did just about everywhere else. Altogether, counting the advertised timetabled stops, minor stops, stations, halts and request points, there were 48 stops in 173 km, some of them on-demand halts without a name — just a km number.

I’m indebted to a Mr Mark Ahsmann who informs us that the Onverwacht part of the line went out of use in the 1980s. Many of the buildings and much of the rolling stock remained in place but had become derelict by the time he visited and took the following photos.

Building at Onverwacht train station.,

Mark Ahsmann – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Train at abandoned station of the town “Onverwacht,

Mark Ahsmann – Licence CC BY-SA 3.0

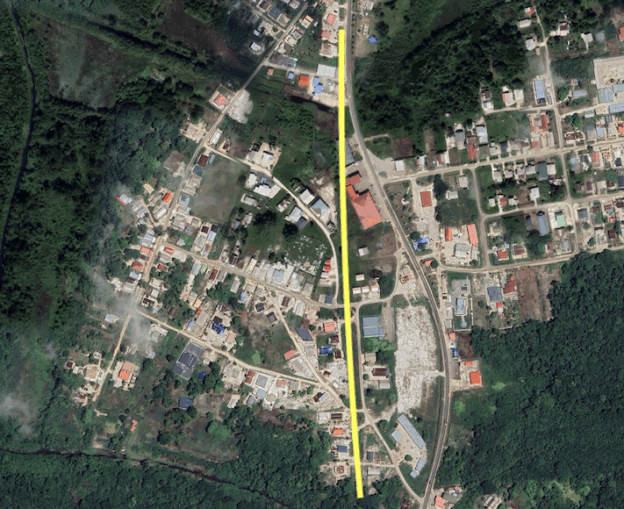

Judging from the aerial photographs, since his visit it would appear the site has been cleared. By matching landmarks (particularly creeks) with a 1930s map of the area’s plantations, I would say the route of the line was as per the yellow line below, with the red shed at the top and to the right — now a Para Fuel service station — being where the station and workshops were.

© Google Maps 2025, Google licence

It is not only myself and Mr Ahsmann who have taken an interest in the steel wheel upon steel rail in these parts. In 1955, Queen Juliana of the Netherlands and her husband, Prince Bernhard, made a royal tour of the Dutch colonies in the Caribbean.

Flying on an October day from Amsterdam, the royal couple were welcomed in the evening at Puerto Rico Airport by the local Governor and other officials before driving to his palace for a short visit. Later, they rendezvoused with the Dutch cruiser De Reyter for a three-week tour of Suriname and the six islands that formed the Netherlands Antilles.

When in Suriname, the newspapers reported a 20-hour trip through the jungle, much of it by canoe. Rowed down the Suriname River by bush natives to visit the interior, when shooting rapids the Queen disembarked and the Prince stayed aboard. Part of this trip was by rail and visited the very interesting Kablestation, which sat at km post 133. Here, the line rejoined and then crossed the Suriname River. Below, the Queen disembarks on an unrepeatable visit to the local hospital named in her honour.

The royal company arrives at Kabelstation,

Willem van der Poll – Public domain

I wonder if that is the same rail car that sits derelict at Onverwacht? It might well be. In 1954, the West German company Linke-Hofmann-Busch/Büssing provided ‘several’ such vehicles for the Lawa.

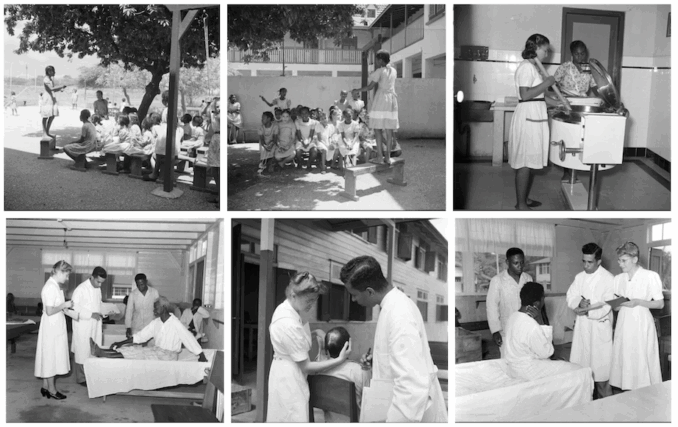

The photographer was Willem van de Poll, who learned his craft between the wars in Vienna, where he became an assistant to film legend Alexander Korda. In 1944, van de Poll was appointed to head the photographic service of the Dutch military forces and rose to become the royal house’s photographer. Eight years prior to the royal visit, he toured the same territory documenting jungle communities. His photographs include the Princess Juliana Hospital at Kabelstation (Juliana became Queen the following year), where he captured the work of Doctor Duurvoort and his staff. Doesn’t it look idyllic.

Sister Agate and Doctor-Duurvoort-in-the-hospital-Princess-Juliana,

Willem van de Poll – Public domain

Too wide for a bridge, at the time of the Queen’s visit, connecting rail services on opposite banks were joined by a ferry. But this wasn’t always the case. If you thought the Paramaribo Ice Plant and the Onverwacht Para Fuel Service Station were interesting, wait till you hear this. Besides all the stops, there was another reason for a ten-hour-plus 173 km trip.

Originally, and hence the name, the two sides of the river were connected by cables running from giant towers standing at Kabelstation Nord and Kabelstation Sud. I’m indebted to the Wesenhagen family, who donated an album of contemporary photographs to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, which is available to the public.

Kabelstation Nord,

Wesenhagen Family – Public domain

Cage in which passengers are transferred with cable,

Wesenhagen Family – Public domain

A trip across the Suriname River,

Wesenhagen Family – Public domain

Cable bridge over the Suriname River,

Wesenhagen Family – Public domain

Kabeltoren Zuid,

Wesenhagen Family – Public domain

Not sure I fancy it! Unrepeatable, not least because the railway line and hospital are now underwater. For after Bronsweg, at km 115, the land is flooded on account of a dam across the Suriname River at nearby Afobaka.

The purpose of the dam is to generate hydroelectric power. As such, it supports a 180 MW power station. In 1958, Suriname Aluminium Company LLC, a subsidiary of Alcoa, the Aluminium Corporation of America, gained an agreement with the Suriname government to build the dam to power a smelter to turn alumina extracted from local bauxite into aluminium.

Construction began in 1961 and was completed in 1964. About 75% of the power generated is used for processing aluminium; the rest is used downstream in Paramaribo. The station began operating in 1965, with the 600 square mile reservoir behind being filled by 1971.

This is named the W. J. van Blommestein Meer after the Surakarta-born Dutch hydrological engineer Professor Doctor Ingenieur W. J. van Blommestein, who presumably had a hand in its development.

In a rare Street View lapse, you can look out over the meer here while contemplating lost railways, jungles, gold prospecting, royal visits, smiling happy and healthy natives, and a gondola crossing of a mighty river in a better world now long gone.

What an interesting place!

© Always Worth Saying 2025