Ah Cricket – the wonderful sound of leather on willow followed by a cucumber sandwich and cup of tea. Rather coldly defined on Wikipedia as “a bat and ball game played between two teams of eleven players on a field at the centre of which is a 22-yard pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two bails balance on three stumps” that pretty much sums up the intent in cold words. Although it’s suggested that cricket originated as a medieval children’s game played in south-eastern counties of England, it was named as a gambling sport within the 1664 Gambling Act.

But my musing isn’t about the origins of the game. My ruminations are on not just the role of fielders in the game, but more importantly, recognition of those who make innings-ending catches.

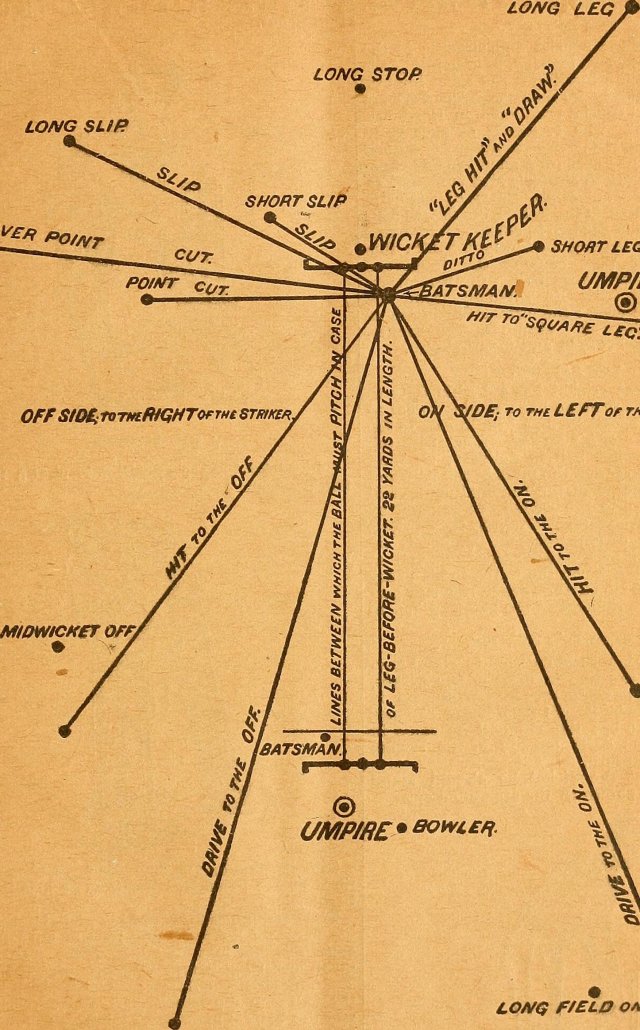

A quick look at the laws tells us (Law 28) that the fielder “is any of the eleven cricketers from the bowling side. Fielders are positioned to field the ball, to stop runs and boundaries, and to get batsmen out by catching or running them out.” Fielders are of course highly skilled players – quick reactions, high levels of concentration, fleet of foot – not to mention the courage needed to step in front of a speeding ball and leap into the air to make a match-winning catch.

It strikes me that the catch-taking fielders are missing out on an opportunity for their own bit of statistical analysis and leader boards. Just a quick look at a scorecard for any match will show us fall of wickets (with the named bowler), bowling economy, strike rates, batting averages and so on. But evidently nothing for the fielders – those who have taken a splendid catch to put paid to a top batsman reaching a match-winning double century!

I was intrigued which I came across the Association of Statisticians and Historians – a global association for cricketing enthusiasts established in 1973. Aha – perhaps an opportunity to show statistics relating to the fielders rather than just the batsman or bowlers. However, the statistics still seem to be limited – and not particularly analytical (unlike bowling averages and strike rates). The Association has tables to show the most catches in an innings or in a match; for Test Matches, they go as far as catches per match over a full career – the table being led by Indian all-rounder ED Solkar (1969/70 – 191976/77) with an average of 1.96 wickets per match. But surely we can do more with all of this rich data available?

Over the summer we have at last been able to watch “The Hundred”. Developed out of the T20 tournament, The Hundred was put forward as a more straightforward game which would engage new audiences. Essentially a form of limited overs cricket, the eight men’s and eight women’s teams face 100 balls in their single innings. These balls are bowled by a bowler in a sequence of 5 or 10 consecutive balls.

So, using The Hundred, I set about exploring whether there was anything else that could be done to interpret this fielding data from the point of view of the catchers rather than bowlers. Taking only the men’s fixtures, I analysed the “catching” data for each of the eight teams – who made the catch and the batsman’s score when the catch was made.

Over the duration there were a total of 253 catches made during the tournament (including caught and bowled) with the catches made by 96 fielders. 4,239 runs were made before these catches with an average of 16.8 runs per catch.

But what about looking at this on a player by player basis. Which fielders would you pick to have in your team?

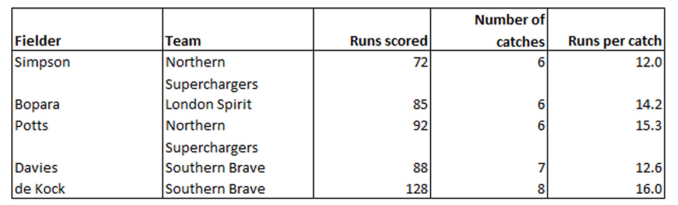

Looking at the fielders who amassed the greatest number of catches over the tournament we have wicket keeper South African International Quinton de Kock taking 8 catches for 128 runs – 16.0 runs per catch. He and Davies – 12.6 runs per catch average for his 7 catches – were both evidently pivotal in Southern Brave winning the tournament.

It could be argued thought that giving away 128 runs is quite costly. What about the fielders who made their catches at the expense of fewer runs?

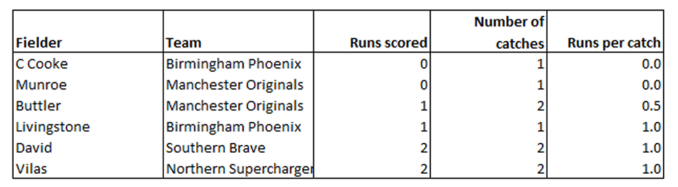

This time the table is led by wicket keeper South African Chris Cooke playing for the tournament runners up Birmingham Phoenix. He made one catch during the tournament (Malan b Pennington c C Cooke being the first wicket of the match).

So my conclusion from all of this data is that getting a batsman out is a team effort – it’s not just the bowler who should get all of the data analysis! The fielder who steps up to curtail the batsman’s innings should also get some numbers to put to their names.

© Mrs Hamster Wheel 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player