In 1955, at the height of the Mau Mau Rebellion, my uncle John Alldridge produced a series of reports from Kenya for the Birmingham Mail and the Manchester Evening News – Jerry F

Fort Hall, Central Province

My new friend, John Pinney, is that almost legendary character, a District Commissioner. At 34 he is the Law and the Prophets to a population nearly as big as Bristol concentrated in a district about the size of his native Dorset.

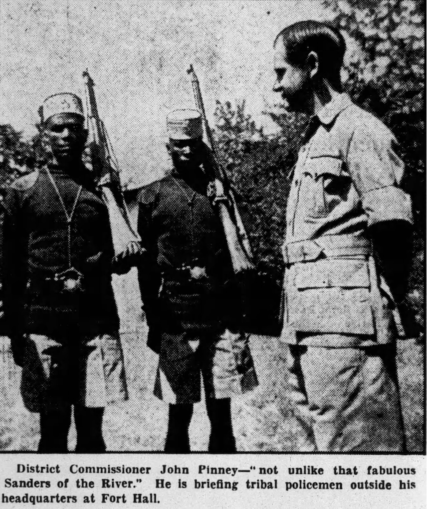

District Commissioner John Pinney,

Unknown photographer – © 2024 Newspapers.com, reproduced with permission

He wears a beret and sunglasses instead of a white pith helmet. And he gets around his 500 square miles of Kikuyu reserve in a Land Rover instead of a stern-wheel gunboat. But otherwise he is not unlike that fabulous Sanders of the River.

To 300,000 sulky, penitent Kikuyu he represents the Queen’s Peace. He has just proved, after as bloody a test as was ever faced by a Roman proconsul, that the Queen’s Peace is not to be trifled with.

This is a smiling, primitive country where until a few months ago to turn away from an African could mean a panga in your back. Now Mr. Commissioner Pinney can take the Governor’s lady for an alfresco picnic within bow-shot of the forest where roving bands of Mau Mau terrorists still lurk — as he did, in fact, the other afternoon. I know, because I was of that party.

He has made this possible by sheer courage and force of character in a part of the world where a man is still judged by what he does, not what he says. And one of the few good things which have come out of this miserable business, which the Kenya Government timidly calls an Emergency and more blunt-spoken observers a bloody civil war, is the speed with which keen and efficient young administrators, soldiers and policemen have come to the top.

When John Pinney took over at Fort Hall at the beginning of 1953 his whole territory was in a state of anarchy. Law and order had completely broken down. In his own words: “You could reckon on a murder a night. Ninety-five per cent had taken the Mau Mau oath in one form or another, and the loyal five per cent were scared out of their wits.”

On the face of it this seems incredible. For on paper these vast Kikuyu reserves were administered on model lines. The policy was to let the African govern himself through democratically elected District Councils. The white Administrator only appeared in an advisory capacity, sitting-in tactfully on innumerable committees.

The inevitable result of this was that the over-worked, under-staffed D.C. became more and more a civil servant, forced to spend the all-important hours wrestling with paperwork in his office when — as he painfully realised — he should have been out there on the Reserve.

And out there, among the hill-top shambas, among the neat plots of maize and wattle-trees, things were going from bad to worse. The subversive poison spread by the teachers of independent schools was turning out a generation of dead-end kids, sulky, dissatisfied without knowing why, ripe for mischief. Old tribal customs, some of them admittedly barbaric, but most based on shrewd common-sense, were flouted. Barefaced graft and corruption made the simplest legal transaction a mockery. Worst of all, the traditional leaders — the chiefs and headmen — had lost face before their own people, underpaid and unsupported as they were by the Government which had appointed them.

Mercifully there were still a few loyal communities led by lion-hearted chiefs who refused to be intimidated. I met one of these the other day: I sat in his simple stone hut and drank his ceremonial tea. He is Senior Chief Mini, 83 years old and proud possessor of an M.B.E., three Coronation medals and 47 wives.

When the Mau Mau hung a dead cat outside his hut and warned him his days were numbered Chief Mini nailed a Union Jack to the village flag-pole and sent back the defiant message: “Come and take it down and see how men can die.”

It was to these isolated villages that Pinney moved resolutely. He turned them into islands of resistance, each secure behind a curtain-wall of bamboo and a moat planted with wicked stakes. Within those walls he recruited his local Home Guard, unpaid volunteers, armed at the beginning with pangas (a local reaping-hook, which when sharpened on both edges becomes a formidable weapon) and spears.

John Pinney, a quietly-sardonic type, who doesn’t pay tributes lightly, has nothing but praise for these Kikuyu Home Guard. “The Kikuyu are an unmilitary tribe, content to get what they want by more subtle methods,” he will tell you. “Yet it was these untrained, untested Home Guard who took the brunt of the fighting.”

Out of the 300 killed in those desperate pitched battles — and they included three British District Officers — 238 were Kikuyu Guard. He believes their stubborn bravery has begun a tradition which more than anything else will shape the future of the Kikuyu. It has given them new respect in themselves and an unexpected affection for, and confidence in, the white men who trained and trusted them.

Certainly their example was an inspiration during the dark days. With the Guard protecting his rear and flanks Pinney, his District Officers, a handful of tribal police and a battalion of the King’s African Rifles was able to take the offensive. He went at it with a drastic vigour that would have warmed the heart of Mr. Commissioner Sanders.

Since the Kikuyu do not take kindly to village life, preferring to live, a few families together, in isolated “shambas” (farms), they could be “chopped” at will by Mau Mau pangamen raiding from the forest at night.

Pinney altered all that by herding them into fortified villages where, 3,000 at a time, they could be comparatively safe behind a high stockade, a moat, and a well-armed guard post. To prevent “collaborators” passing food to their relations in the Mau Mau ranks he slapped the villagers’ reserve of food under lock and key.

Altogether he has built 150 of these new villages in his district. He has driven 500 miles of new red dust roads up hill and down dale. He has planted 15 police stations at strategic points and — the final deterrent — once the Mau Mau began to spend more and more time in the forest he cut them off from the settlements with a more formidable defensive wall — a “bamboo curtain” 25 miles long and never less than eight feet high, with watch-towers covering danger-spots.

And he will tell you, with a certain grim relish, that all this work was done by the “bad lads” of the village, pressed into forced labour gangs.

For one of the remarkable features about the Kiktiyu rising has been that never once has the Administration failed to identify its enemies. As soon as it seemed obvious that the tide was turning and the defenders could take the offensive at will, Pinney and the other D.C.s in the affected areas introduced an ingenious system of public confessionals by which penitents have voluntarily admitted their wrong-doing and — more important still — the names of their associates.

Now this process of turning a man into a “stool-pigeon” may seem repugnant to Western minds but this is not Birmingham. This is Africa, where — as I am continually being told — the law by which men live is still very much the law of nature.

For nine months there has been comparative peace in the reserve. The slow work of reconstruction is going on. As usual, it is the young and innocent who have suffered most. And one of the most heartening things I have seen on this tour is the sight of Miss Marjorie Houghton of the British Red Cross driving her “milk cart” 100 miles a day, five days a week, to bring free milk and medical attention to under-nourished Kikuyu children.

There is a brand new hospital at Port Hall; and while I was here they began a helicopter-ambulance service which can fly the dangerously sick over the hills from hut to hospital in a few minutes.

A more grim reminder — there is also a new Repatriation Camp, where Kikuyu, drifting back to the Reserve from all over Kenya, can be “screened” before picking up their lives again.

It would seem that a weak, badly-frightened administration has learned its lessons in time.

Before the “emergency” Fort Hall had one District Commissioner and one District Officer. Now it is divided into four divisions each under its own District Officer. Each division is sub-divided into an average of five locations, each in turn cared for by a District Officer (Kikuyu Guard). And at headquarters is District Commissioner Pinney and a headquarters staff of three D.O.s. In addition it is intended that each divisional D.O. will be helped by an Administrative Assistant, preferably an African, who will look after the paperwork while the D.O. gets around the “parish.”

Loyal headmen and chiefs are gaining new prestige: they have had a handsome increase in salary. And that, in the eyes of the money-loving Kikuyu, means a very great deal.

But these are only superficial details. The roots go much deeper. John Pinney, who has just won a mighty close-fought war, has now to win the peace.

“Our whole future policy must rest on the loyal chaps who stood by us when things looked hopeless,” he will tell you. “They must have preference now. If we forget them and let them down — and war heroes are tragically soon forgotten — then what we have been through is only a foretaste of what will come.

“You see, the poison is still there. If we are going to drain it off we must restore to the African on the Reserve something comparable to his traditional way of life which we have, in all sincerity helped to destroy. We must do something about this generation of “dead-end kids.” The young Kikuyu is hungry for education. We must see it is the right kind.

“For whichever way you look at it, the East African is going to be our responsibility for a long, long time. He is still awfully immature; from my experience it will be several decades before he is ready to run his own affairs wholly on his own.

“For that reason we must have a strong administration that knows its own mind. We must stop squabbling among ourselves. To the African mind, that only spells weakness and indecision. And weakness in the long run can only mean disaster.”

Reproduced with permission

© 2024 Newspapers.com

Note: Sanders of the River is a 1935 British film directed by Zoltán Korda, based on the stories of Edgar Wallace. It is set in Colonial Nigeria. – Wikipedia

Jerry F 2024