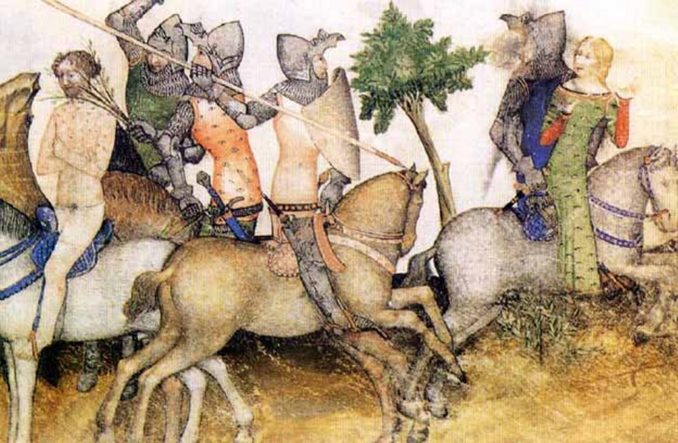

public domain

It has been too long since I offered up to the folk of this parish a ‘deep dive’ of my literary musings. I’ve a scattering of unfinished articles but something somewhat meatier was needed to make up for the delay.

Therefore, I present below an extract of the Prologue to the Canterbury Tales. It’s a biggie, a toughie. It is as unfamiliar as it is familiar. The words themselves speak though over the centuries and hark back to almost-untouchable time: they wrap us up in a cloak of comfortable excitement in their familiar unfamiliarity, in no small part owing to the perfectly executed meter and couplets raining pearlescent on our ears after nearly 700 years.

The following, for context, I have taken from the Introduction in my Everyman’s Library copy by D. Pearsall (1992):

Chaucer is presumed to have begun the Canterbury Tales around 1387, when his busy career as a professional civil servant and office-holder [Controller of the Wool Customs in the Port of London] was temporarily in abeyance and he was living … in Kent. It marks a new phase in his poetic career. All his major poems up to this point…had some connection with the court and court audiences and took as their ostensible themes the preoccupations of courtly society…

The familiarity it has acquired in centuries of readers’ experience disguises its innovativeness… When Chaucer died, the work was still in progress, and existed in the form of a series of fragments, some of them in differing sates, bearing the marks of ongoing revision. There is no ‘authoritative’ manuscript…, nor any manuscript which suggests that Chaucer, during his lifetime, prepared the work for ‘publication’.

The lines below are the first 42 of the Prologue from Fragment I (Group A). They describe to the reader how in spring the narrator lay in the Tabard Inn in Southwark, ready to embark on his pilgrimage to Canterbury, he falls in with a group of wel nyne and twenty other pilgrims whom he joins for his pilgrimage. The prologue continues to outline who is in the company with a little background to each.

Chaucer’s masterful taletelling is crystal clear; there is no waffle or loose lines. It’s highly efficient and, most importantly, it’s engaging. Within these first forty two lines we understand who the narrator is, where he is, why he’s there and his intentions. The narration itself is poetic without being flamboyant; it’s mostly grounded (save referencing Zephirus), pastoral and rural. It doesn’t speak down to the reader: it speaks to him. It reminds us of Shakespeare’s Chorus in the opening of Henry V: the metre sets an upbeat pace and each line flows fluidly to the next.

A couple of notes before you delve. Read the lines aloud in an accent: Black Country or Geordie if possible (for reasons I hope to outline in an article one day). There are rarely silent letters. On the whole, try to suppress your modern English and pronounce as spelled. Generally, should a word end in an e, pronounce it as an extra syllable.

The iambic pentameter is perfectly executed and you should therefore be able to feel when you get the stresses and syllables correct (there are a few variations throughout for some linguistic purpose but nothing too troublesome).

I have not provided a direct translation to modern English. That would be no fun and there is a joy to be had in seeking out the meaning of the line yourself. I have, however, added some prompts in a lighter text colour and notes where understanding is unlikely.

Finally, it can be of great assistance in hearing the text read out aloud in (what we believe to be) original pronunciation. The youtube link here should assist in this. It also provides a phonetic text of pronunciation:

HERE BYGYNNETH THE BOOK OF THE TALES OF CAUNTERBURY

Whan that Aprill with his shoures soote

showers sweet

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote,

drought pierced

And bathed every veyne in swich licour

Of which vertu engendered is the flour;

By virtue of which the flower is produced;

When Zephirus eek with his sweete breeth

Also breath

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne

tender crops young sun

Hath in the Ram his half course yronne, 1

And smale foweles maken melodye,

That slepen al the nyght with open ye

eyes

(So priketh hem nature in hir corages);

Incites hearts

Than longen folk to goon on pilgramages,

go on

And palmeres for the seken straunge strondes,

seek shores

To ferne halwes kowthe in sondry londes;

to distant shrines, well known in different lands (e.g: “all and sundry”)

And specially from every shires ende

Of Engelond to Caunterbury they wende,

go

The hooly blisful martir for to seke,

seek

That hem hath holpen whan that they were seeke. 2

helped sick

Bifil that in that seson on a day,

It happened

In Southwerk at the Tabard as I lay 3

Redy to wenden on my pilgrimage

To Caunterbury with ful devout corage

heart, spirit

At nyght was come into that hostelrye

Well nyn and twenty in a compaignye

company, group

On sondry folk, by adventure yfalle

assorted fallen in to by chance

In felaweship, and pilgrims were they alle,

all

That toward Caunterbury wolden ryde.

would ride

The chambres and the stables weren wyde

spacious

And wel we were esed atte best.

eased

And shortly, whan the sonne was to reste,

So hadde I spoken with hem everichon

everyone

That I was of hir felawshipe anon,

immediately

And made forward erly for to ryse,

early to rise

To take our wey ther as I yow devyse,

tell

But nathelees, whil I have tyme and space,

Er that I ferther in this tale pace,

Before I proceed further in this tale

Me thynketh it acordaunt to resoun

reason

To tell yow al the condicioun

Of ech of hem, as as it semed me,

each

And whiche they weren, and of what degree,

And eek in what array they they were inne;

also

And a knyght than wol I first bigynne.

will I first begin

<Proceeds to outline the pilgrims of the Felaweshipe>

Notes

- The young sun (i.e.: the sunn at the beginning of its annual journey) has completed the second half of its course in the Ram. (The sun had left the zodiacal sign Aries, which is did in Charcer’s time on 11th April. We know from the Intro to the Man of Law’s Tale that the first or second day of the pilgrimage was 18th April) [Cawley, 1992]

- I.e.: St. Thomas Becket

- https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryMagazine/DestinationsUK/The-Tabard-Inn-Southwark/

© Cromwell’s Codpiece 2023