The screaming started shortly after daybreak; the women and children had spent the night in the schoolhouse for the children of the Pilsudski Settlers. Throughout the night the women had taken it in turns to look out of the window overlooking the underground vegetable cellar into which the “Polish Kulaks” had been pushed by the NKVD and their “White Russian” collaborators.

Shortly after dawn three NKVD soldiers had arrived with a small table, stools and bottles of vodka. They were accompanied by six local White Russians wearing armbands, two of them carried rifles and another carried an axe.

One by one the Polish farmers were dragged from the bunker and killed with the axe. Throughout this the cries and screams from the schoolhouse rose in intensity only to be replaced by a constant weeping once all the farmers were dead. An hour later the NKVD and their collaborators had finished the vodka and marched the women and children out of the schoolhouse some 20 kilometres to a rail line where cattle cars were waiting.

Bob was born in a wooden shack in the “lands beyond” in October 1925 to Anton and Monika. Anton had fought in WW1 and also in the Polish-Soviet war that finished in 1920. The “lands beyond” were also known as the Kresy and after the Polish-Soviet war, Polish soldiers who had fought the Soviets were awarded farmsteads in the Kresy by Marshall Pilsudski the President of Poland; those receiving farmsteads were therefore known as Pilsudski Settlers. In reality the farmsteads were just a plot of land, no more no less. No building materials or equipment were provided and just like in the Wild West, these settlers of the wild east had to provide these from their own resources.

The settlers built their homesteads from scratch on a plot of about 20 hectares. The idea was that having armed ex-soldier settlers on the border facing a potential enemy like the Soviets would provide a buffer if the enemy rose again. The Kresy or “lands beyond” consisted of territory gained by Poland at the Treaty of Brest Litovsk. It comprised of parts of Belarus, Russia and Lithuania. It was a curious place as the territories also contained Russians who could have returned to the Soviet area of control but chose not to. The Polish Settlers tolerated them and called them “White Russians” as they were clearly not as “Red” as their Soviet brethren but relations between the various ethnic groups would never be easy.

The Settler plot awarded to Anton was about 40km from the now Lithuanian capital of Vilnius. Today it is about 2km inside the Belarus border and nestles on a bend in the river. There was nothing there, Anton and the other Settlers built their plots from nothing; felling trees to establish farmsteads that would support them and their families.

Anton worked hard and in time the family occupied a wooden cabin, later some outbuildings were erected and a farmstead with some cows and horses was established. However, it was still primitive, Bob would recall how on a winter morning he would have to break the ice on the water trough and warm the icy water in his mouth in order to take a wash. Throughout this time of development and betterment, relations with the White Russians did not improve who envied the industriousness of the Poles. Over time Anton and Monika had six children, two of whom were to die early from disease, there were no hospitals in the lands beyond.

The eastern area of the Kresy where Bob was raised was perhaps the poorest of all of the lands beyond, a picture of Bob at eight years old taken at the cabin that served as the Polish schoolhouse shows all the pupils in ragged clothes with only two of the twenty-five children having shoes, Bob was not one of those with shoes.

In October 1939 following the Soviet/Nazi conquest of Poland in line with the Molotov/Ribbentrop Pact the Soviets arrived in the Kresy. This unnerved both the Settlers and the White Russians neither of whom had a liking or allegiance to the Red Russians, but things were quiet. The Soviets moved into the nearby cities and started to liquidate nationalists’, teachers and priests and other potentially traitorous elements in order to build their Socialist paradise and the rural countryside was largely untouched by the NKVD presence although some teachers and priests disappeared.

It was not until late Spring and early summer of 1940 that the Soviets turned their attention to the Kresy Settlers, at first NKVD officers and soldiers appeared with local White Russian helpers who were wearing armbands and who assisted the NKVD to identify the settlers. Inventories were taken of animals, stores and equipment and the NKVD left. The NKVD were in no hurry they regarded the White Russians as traitors to the motherland but for the moment the need to deal with the Polish Kulak Settlers was more pressing; there would be plenty of time to deal with the White Russian traitors once the Poles were gone.

In June 1940 the NKVD again appeared at the farmstead. This time they had an agenda, Anton was taken away on a cart; the rest of the family including Bob were given 15 minutes to pack a small bag and they were then taken to the nearby schoolhouse. Bob was convinced his horse was crying as he was taken away. At the schoolhouse Bob, his mother, his two sisters and his brother were locked up along with the wives and children of the other Polish farmers.

In the meantime, Anton and 11 other Settler farmers were pushed into an underground vegetable cellar about 50 yards from the schoolhouse by the White Russian helpers who were by now very keen to establish their solidarity with both the Soviets and the NKVD. The killings occurred the following morning.

The bodies of the Settler Farmers were thrown into an unmarked pit at the edge of the village and the Settler farmsteads were looted by the White Russians. Some years latter a White Russian who was present at the killings was to tell the Polish Commission who investigated the killings of the bravery of the Settler soldiers mentioning that they demonstrated typical Polish stubbornness and that not even one had begged for his life. Perhaps this had something to do with the exclamation shouted by Anton. He was the first to be taken and as the White Russians took him out, he shouted, “Be brave boys if you believe in God you have nothing to fear.” If anything, this angered the White Russians who were fawningly obsequious towards their new Soviet masters and who perhaps at the back of their minds realised that the fate that awaited them within a few months would be little different to the one they were dealing out to the Polish Settlers.

After reaching the rail line Bob and his family were loaded onto the train which departed on its long journey with Bob, his mother and his siblings settled into a cattle car courtesy of the NKVD. Whilst the train was being loaded the White Russians smelled the opportunity for looting the farms and also the opportunity to demonstrate their allegiance to the Soviet Motherland. What remained of the Settler families now faced a six-week journey to the Gulag.

The train would occasionally stop and those that had died were thrown out and a pail of bread, another of rotten vegetables and one of water would be placed inside by NKVD guards. The cars were not overcrowded but in Central Europe summer temperatures would easily reach 30 degrees centigrade and for those inside the locked cars the temperature was much higher. At this time Bob did not know that he was only one of one to two million Poles deported from Polish territories by the Soviets; many of these Poles would never see Poland again.

The train finally reached the railhead in Kazakhstan and Bob, his mother, his sisters and his brother were taken into the Gulag. It was not a Gulag of the type you might see on the TV, it was a “family” Gulag, at first Bob and his family were housed in a bell tent with the sides set into the earth, later they were to share a single room in a wooden cabin with 6 other Settler families with the room being divided by curtains. As a 15-year-old “man” Bob was required to work each day and he had to walk up to 10km to various worksites where he was required to work for 12 hours before returning to the Gulag.

Work was hard; the worksites paid the NKVD for the labour provided; therefore, Bob felled trees and did whatever was asked. As winter arrived temperatures fell and having no winter clothes Bob had to improvise by binding spare bits of cloth to his arms, feet and legs in order to try and keep warm. If Bob did not work or if he failed to meet his work quota the family went hungry as the NKVD would withhold food rations, not that these had much nutritional value anyway as they were mostly rotting vegetables. The NKVD traded any prisoner-allocated meat for vodka and also traded better quality prisoner bread with the locals for sawdust bread (and more vodka for themselves) to give to the Polish prisoners. Every day when Bob returned to the Gulag there would be some corpses laid out for inclusion in the roll call and who would possibly hear the warm thanks that the prisoners were required to shout to Marshall Stalin for his generosity in removing them from their decadent and bourgeois existence. This continued for 18 months until early 1942 when Stalin suddenly declared the Polish prisoners were to be released.

There then started an exodus from the Soviet Gulags to Persia, some of the Poles imprisoned in the north of Russia or Siberia had to travel 1,000s of km without assistance. The lucky ones who were near to sources of transport did what they could but many walked the entire distance with countless numbers dying en route. In Persia the Poles were assembled in camps by the British Army. Bob and his family reached Persia some three months after leaving the Gulag, having walked, travelled on lorries and trains to get there.

At first the refugees lived in family camps and Polish schools were established, Bob went to school again and started to learn English along with other Settler children. Professional Polish soldiers that had survived the Soviet camps or teenagers of Army age were offered the chance to enlist in the 8th Army.

© Novak and Goode 2023, Going Postal

Bob went to Polish school for a couple of weeks but decided it was not for him. Soon he found himself with some of his newfound friends standing in front of a British Army recruiting officer. Bob could not understand the British officer and the officer could not understand Bob; translation was provided by a Polish interpreter who answered “correctly” any question asked by the British officer. After lying about his age Bob was now officially a soldier in Polski 2 Korpus (Corps) and part of the 8th Army. The NCOs of 2 Corps made sure those that had lied about their age were placed outside of the infantry and Bob found himself as a gunner on 7.2-inch field guns; the “younger” Poles were often allocated to the guns as given the range of the weapon it was usually the case; they were situated some way behind the front line and it was judged to be safer than being in the infantry.

Bob had only been in uniform for a couple of weeks when he was taken ill, soon his condition rapidly deteriorated and he was hospitalised. Bob had contracted typhus which was prevalent in the Gulags. He was sent to a British Army field hospital but a few of his comrades insisted on going with him. They did not trust the British medics who did not speak Polish and they had seen more typhus in the Russian camps than the British would ever see. For seven days they stayed by his side talking to him in his delirium in Polish and bringing him water until his illness had passed, Slowly Bob recovered and returned to 2 Corps. In the meantime, his mother and siblings were shipped to a British camp in India where they were to spend the duration of the war; Bob was never to see his younger brother again.

The first action that Bob was to see was at El Alamein, he would later recount that the British barrage was so intense and enduring that night became day. After this battle, Bob and 2 Corps followed the 8th Army through North Africa until the campaign concluded.

Before leaving North Africa, 2 Corps took part in the victory parade in Tunis. Bob was to gain a liking for the warm sunshine of the Mediterranean that was to stay with him throughout his life. After Africa, 2 Corps next took part in the landings at Anzio in Italy although, by being in the heavy artillery Bob was not with the first assault wave, he came ashore a couple of days later. I recall watching an episode of the World at War series with Bob that covered the Italian campaign and during the programme some footage of a crashed Spitfire on the Anzio shoreline was shown; Bob became excited, “I saw that,” he said; he went onto recount that after they started to move inland they saw a twin boomed aircraft overhead, they paid little attention as they thought it was an American P38 Lockheed Lightning, it was however a German Focke Wulf FW189 which returned to bomb and strafe the column.

The next action that Bob took part in was in the foothills of a mountain with a monastery atop. They bombarded the monastery throughout the period from February to May 1944 and he witnessed several ferocious airstrikes before troops tried to take the hill and then complete destruction by Allied bombers of the town of Cassino below. There were three separate attacks made in this period by both British and New Zealand troops as they tried to dislodge the German defenders of Monte Casino. Each attack failed and the fourth assault was made by troops from Polski 2 Corp, The Polish attack was successful and the by now demolished monastery site was captured allowing the Allied advance to continue. Bob did not take part in the assault other than as a gunner and his unit hurled an enormous amount of shells against the Monastery and the hillside. One thing that struck all the Allied units was how few German prisoners the Poles brought back from their successful assault. It was also during this time that Bob was to meet with a more irregular recruit to 2 Corps named Wojtek, you can read the story of Wojtek here.

© Novak and Goode 2023, Going Postal

After Monte Casino, 2 Corps went with the Allies up to the top of Italy and the Austrian border. There the majority of them were halted although a few Polish units did see action in France. Bob would always say they were halted as the Allies were worried that the, by now, sizeable Polish Army (some 100k strong) might continue fighting all the way back to Poland. The Poles were dispersed to camps which they ran with great efficiency, establishing postal services with other camps. In this time Bob found a Harley Davidson 45 in a ditch. The bike did not work and Bob took it back to the camp, there with help from the motor pool he got the bike running and used it to travel outside of the camp.

The end of the war came but the fate of the Poles had been agreed at Yalta, they were supposed to be returned to the Russians. The Poles had experienced their fill of Soviet Communist “hospitality” and knew what it was likely to entail. A small group were desperate to return to Poland and left, they were taken to the border with the Russians in Austria by British troops and handed over; they were never heard from again. The British were reluctant to force the Poles to return (unlike the Cossacks who were forcibly returned by armed British troops who reported they could hear the gunshots as the Soviets executed those who had just been handed over) because the Poles (unlike the Cossacks) had fought loyally for the 8th Army. In dribs and drabs they were brought to the UK from camps in Italy and in early 1946 Bob found himself in Scotland, still in uniform but working on the railways to relay and renew track in work groups comprised of Poles. Like all the other free Poles, Bob wondered why the Poles had not been brought to the UK sooner and also wondered why no Polish troops were allowed to take part in the VE Day victory parade. It was to later be established they were excluded as the UK Government did not wish to upset the Russians through the inclusion of the Free Poles.

© Novak and Goode 2023, Going Postal

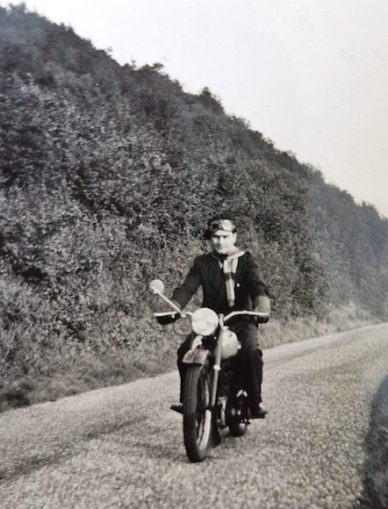

In mid-1946 Bob was demobbed and moved to Birmingham where he found a job at Cadburys. His English was improving and he was part of a community of Polski 2 Corps men who had been placed within various industrial enterprises within the city. It was at Cadburys that Bob actually became Bob as his Polish name was too difficult for the English to pronounce. In time Bob saved enough money to buy himself a BSA B33 500cc motorbike. He worked hard and later saved enough for a deposit on a small terraced house in Aston, he rented out rooms to other 2 Corp soldiers one of whom was called Ted. Ted was a professional soldier, a sargeant major in his early 50s, he had fought in the First World War; the Polish-Soviet War and from the very start of WW2, fighting the Soviets who invaded the eastern half of Poland whilst the Nazis invaded the western half. Ted was lucky he had only been sent to a Gulag whereas many of his comrades had ended up at Katyn or one of the other murder sites utilised by the NKVD for killing Polish officers and NCOs, like Bob he had joined 2 Corps after release from the Gulag.

© Novak and Goode 2023, Going Postal

Life in Birmingham was good for Bob and for Ted, both worked hard and Bob got a job at a garage as a mechanic. Their life was very much within the Polish community in Birmingham and in the early 1950s the Polish community raised enough money to buy a building in Digbeth that became a Polish Centre/Social Club. One day in the late 1950s Ted showed Bob a photograph of a young lady, “What do you think?” asked Ted smiling. “She is pretty,” said Bob “are you thinking of marrying her?” Ted replied, “Don’t be a fool it is you that should be thinking of marriage, she is my daughter!” The lady in question was called Martha, the problem was that she still lived in Poland, after much wrangling Bob and Ted were able to get a visa for Martha and her mother to come to the UK and Bob got married. Over time he had managed to save enough money to move to a much larger 1920s semi in Handsworth which at the time was a quite salubrious area and over the next few years he was able to raise a family of four daughters.

© Novak and Goode 2023, Going Postal

In the early 1960s Bob had a quite reasonable win on the pools and found he had enough to buy a brand-new car. He bought a Ford Consul and after much thought decided he would travel back to Poland to visit his mother who had ended up there following time in a Polish camp in India. It was not to be an easy visit from the time he arrived he was followed by the Polish Security Services who had no difficulty keeping tabs on what was probably the only brand-new Ford Consul in Poland. After a few days Bob knew his visit was making things difficult for those that he went to see and so he drove back to the UK.

Back in Birmingham Bob continued as a mechanic at the garage, his new house had a large double garage and he would often spend the evening working on friends’ cars so that he could support the three generations of family who lived in the house. Over the next 30 years he watched the area decline, because the houses in the road where he lived were large four or five-bedroom properties; one by one the houses were bought up by the “new” British who would immediately build the biggest possible extensions and turn the garage into another room or two. Bob was astonished as to how they could do this, especially as it seemed none of these new neighbours had jobs or went to work.

Bob retired at 65 and it had been on his mind for some time to go back to Poland to visit what remained of his family following Polish independence. His mother had died some years before but he still had sisters. In 1993 he arranged with an old 2 Corps tank driver companion that they would drive there; his friend had a Ford Fiesta and it took them three days to reach the Polish border driving continuously in shifts. Bob stayed with his older sister in Masuria (part of N.E Poland) from there he visited remaining family members and also decided to go to Belarus if he could, to try and visit the farmstead in the Kresy.

Relations between Poland and Belarus were “informal” at the time and for $30 Bob was able to buy a 24-hour pass at the border to enter Belarus. Bob and his sister went straight to the site of the farm but there was nothing to see. Back in the village the schoolhouse was still standing and the village had grown little. The locals were suspicious, “Why was he there?”, “What did he want?” Bob explained and the locals started to think he had come back to find his property that they had stolen and they started to drift away. One older man remained, he explained that he was “thirsty” and if they had some small money for a drink his memory might improve. From the boot of the Fiesta Bob produced half a litre of Koshena vodka and gave it to the man. The man asked Bob to take him on a short drive; as they drove to the edge of village the man went to great pains to say he could only tell them what he had heard about the fate of the Settlers and that of course, he was in no way involved in their fate, as Bob drove the man started swigging the vodka. After a few minutes he told Bob to stop the car, there by the side of the road was a crude concrete cross about two metres high.

They all got out to take a look, the old man said the cross had been erected after the war by the Polish War Crimes Commission, there had been a plaque at the base of the cross but some “bad people” had taken it some years before. The cross marked the pit into which the bodies of the Polish farmers had been thrown. As Bob took some photographs the man continued to swig the vodka which had the effect of loosening his tongue. Eventually they got back in the car and drove the old man back to where they had met him. As they talked with him it seemed he knew more about the killings than he had suggested, some of the things he said made Bob think he had been at the killings as they were details that were more likely to have been seen than heard about. They dropped the man off and with a heavy heart Bob crossed back over the border into Poland. Within a couple of weeks, he had seen all the relatives who were still alive and he came home, Bob never again returned to Poland.

He continued from time to time to fix cars for his friends although the work was becoming harder and harder. He loved nothing more than sitting in the garden on sunny days and said the hot weather reminded him of his time in Italy. His love of the garden was blighted enormously when his “new” British neighbours built a giant two-storey extension along the fence line that seemed to take up most of their garden. Every now and then at night he would be woken by what sounded like gunshots and one day a neighbour across the road was murdered. It was nothing like the area it was when Bob had moved there.

One morning Bob woke up, he got out of bed but did not feel well, he was complaining to Martha that he was cold when he collapsed. Martha had trained as a nurse in Poland but was unable to revive him, Bob had suffered a massive heart attack; the typhus he had caught in North Africa had damaged his heart and it now finally caught up with him.

You might be wondering dear reader how I know so much about Bob, well some 34 years ago I married one of his lovely daughters.

© Novak and Goode 2023