In 1969, my uncle, John Alldridge visited New Guinea to “observe the attempt to weld a primitive people to a modern society”. This is the third of his reports for the Vancouver Sun. – Jerry F

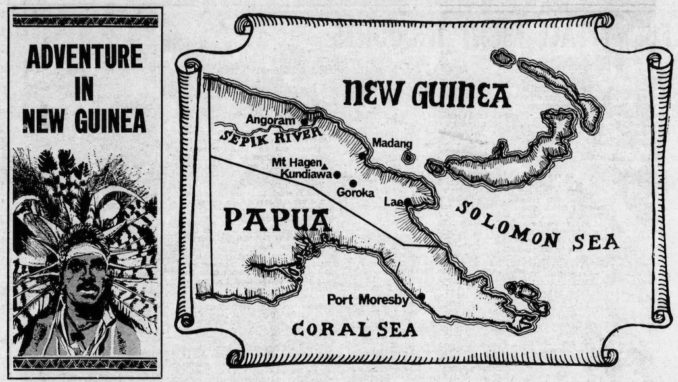

Adventure in New Guinea,

Vancouver Sun – © 2022 Newspapers.com, reproduced with permission

“This is the last of the real ones,” said the Patrol Officer sadly. “They will never be quite the same again.”

We had met at the Mount Hagen Show, where he was doing reluctant duty in the press box. We had sneaked away to the bar to lay the dust kicked up by 15,000 pairs of naked stamping feet and get away from the smell of rancid pigs’ fat mixed with charcoal.

It had been a thrilling show. All those thousands of glistening warriors in their war-paint. All those incredible headdresses that would have sent a Mayfair hairdresser berserk. All that shouting and keening as tribe rivalled tribe in fifty different dialects. A unique spectacle. Probably nothing quite like it to be seen anywhere else in the world.

Altogether a remarkable achievement. In a country where neighbour is by nature suspicious of neighbour — where Papuans despise New Guineans, the Bukos hate the Tolais, the Tolais hate the Sepiks, and the Hanuabans hate everybody — this annual get-together does seem to be helping to bring a polyglot nation toward being something like a family of peoples.

But I could see what the Patrol Officer meant about the show never being quite the same again.

When the first show was held in 1961, so naive were the performers, so untouched by civilization, that one violent little warrior had to be restrained by the police when he wanted to drive an arrow through a photographer. Today they were posing for their photographs with all the blasé complacency of film stars. By next year, no doubt, they will have worked out a union rate for the job.

Sophistication is catching up fast on these last of the Stone Age people.

At today’s performance there were umbrellas — the latest spring button model from Japan — slung with the spears and tomahawks.

Many wristwatches were in evidence, sometimes one to each sinewy wrist. At least one noble savage was wearing a natty tartan waistcoat with his feathers and bark skirt.

And the moment the show was over riot police moved quietly in to patrol the bars in Mount Hagen.

With the possibility of 30,000 primitives who have acquired a taste for liquor going on the rampage there could be a hot time in the old town tonight.

Small things in themselves, perhaps. But they worry the Patrol Officer, who, like all the rest of his kind, loves these simple but highly volatile people and has given the better part of his life to them.

The New Guinea Service is a glamorous but demanding life. To be a success in it a man has to be half Canadian Mountie, half Sanders of the River.

Because it offers an adventurous career where there is always a chance of danger it has attracted a very special kind of recruit; a breed of men difficult to assess by ordinary standards.

Men as different as the legendary Jack Hides and the even more legendary Errol Flynn — who was not a success as a Patrol Officer, to put it mildly.

Flynn is still remembered around Port Moresby as a dashing tennis player who cut a swathe among the wives of planters and officials while their husbands were up-country.

Oddly enough, Errol Flynn and Jack Hides were close friends; the streak of flamboyance in Hides appealing to the more experienced Flynn.

Jack Hides — Jack-a-Hide as he was known and loved by the native people of Papua and New Guinea — packed more living into his 32 years than most men can manage in a lifetime.

He was an assistant resident magistrate not yet 30 when, in 1935, he made history by discovering a Papuan Shangri-la where the Tarifuroro and Wagafuri lived in valleys until then undisturbed.

On the sterner side it was Jack Hides’ boast that he had arrested 150 murderers with the loss of only one life.

In Hides’ day a Patrol Officer’s prime duty was discreetly described as “pacification.”

Today, in addition to keeping the peace, each of the service’s 600 “outside men” must, among many other things, be something of an educationalist, an expert in local government, a marriage guidance counsellor, and registrar of births and deaths.

At the same time the Patrol Officer must be the law and the prophets to every man, woman and child in his area — which might be anything from 200 to 2,000 square miles.

In his day Jack Hides (and if you would read more about this remarkable young man let me recommend to you James Sinclair’s excellent biography The Outside Man, just published by Angus and Robertson), walked thousands of miles through some of the most difficult country in the world.

The Patrol Officer today may have a Land Rover and get his supplies by air; he may be able to keep in touch by radio. But the bulk of his patrolling is still done on his feet.

Only five years ago Patrol Officer J. D. Fitzer led an epic patrol into the Star Mountains. Accompanied by P. O. Ross Henderson, 10 police, and 30 bearers he spent three weeks exploring country from two to eight thousand feet high.

They climbed mountains, crossed flooded rivers and hacked a path through the jungle with bushknives to find a lost world and a tribe which did not know that a world existed outside their valley.

“If it does nothing else, a couple of weeks’ patrol on foot certainly sorts out the men from the boys,” my Patrol Officer assures you. Like the old-fashioned cop on the beat, the Patrol Officer lives very close to his people. And his people are very close to him.

He is their kiap. He is the man they turn to with a hundred problems. And what he says goes.

But as the eastern half of New Guinea — which is a Trust Territory administered by Australia on behalf of the United Nations — moves swiftly towards self-government, at the urgent insistence of the UN, my Patrol Officer is not happy at what he sees and hears in his villages.

On the surface, it’s true, all seems set fair.

Almost the whole of the territory of Papua and New Guinea is now under a system of local government very much like our own. Already 800,000 out of a possible 3,000,000 people elect their committeemen, vote for their representative on the tribal council, for their member of Parliament.

But in almost everything the tribesman still turns to his kiap. And—remembering what has happened in Africa — my Patrol Officer is worried about the future.

“Our big problem is going to be to get enough local men sufficiently well educated and responsible to take over the job when we go.

“We Australians are always boasting about how democratic our education system is out here. But what happens in practice? The lucky kids go to school and leave after four or five years. They come back to the village, think they’re better than the other men, and won’t work. Simply because they can speak English; which most of them will have forgotten after they’ve been back a couple of years.”

Although the United Nations frowns on pidgin — a bastard language that almost everybody in New Guinea speaks — being taught in schools, my Patrol Officer, like most white officials I have met, is in favour of a bilingual system.

He would like to see pidgin recognized as the common language in a country which already has 700 languages and 500 dialects and English reserved as the official language.

When you mention independence he laughs wryly.

“Not one per cent of the people here have the faintest idea what the word means. These Highlanders, the most conservative, clannish people on earth, have always been opposed to self-government, anyway. Their whole way of life is against it. And it doesn’t help to see themselves being governed — as they see it — by a minority of upstarts on the coast.

“They don’t want us to go; not yet anyway. Because they know that, with all our faults, we are the only defence they’ve got against their own people who would exploit them and the Indonesians on the other side of the border who would move in as soon as we left.”

It is a view held, too, by many Highlands members of the young House of Assembly at Port Moresby.

There is a hard-headed realization that their people are still far from ready to control their own affairs. And visiting United Nations delegations who insist that they should get a cold reception.

Sanake Giregire, member for Goroka predicts it would be “three or four thousand years” before the territory could rule itself.

The member for Minj, Kaibelt Diria, recently told the Assembly — speaking in pidgin: “Our children who are yet unborn can make this decision. I do not speak English. I do not read books. I do not understand, and I do not want to govern my people.”

Ask my Patrol Officer how long he thinks it will take before New Guinea is ready to govern itself and he will tell you, emphatically: “In excess of 20 years.”

By which time he will be retired anyway; and back in Australia growing roses.

Reproduced with permission

© 2023 Newspapers.com

Jerry F 2023