In 1954, as the centenary of the end of the Crimean War approached,

my uncle John Alldridge produced a series of articles for the

Manchester Evening News which vividly described that campaign.

In this article, the words are his; the choice of illustrations is mine.

Jerry F

“Theirs not to reason why. . .”

I have been reading a letter. A letter written by a British soldier on active service to his mother in Lancashire just over a hundred years ago.

It is scrawled in pencil, as most soldiers’ letters are. Here and there the round, childish writing has skidded off the page, as if numbed fingers have lost control.

“We have no firing to cook with, but when we come across a tree we down it for fuel. We are poisoned with vermin and dirt; the men are dying with cold and exposure; we are tenting it and are in the open air 20 days out of the month, watching the enemy, and there is every sign of of our remaining in this position for the winter.”

I do not know his name. For only two pages of that pitiful letter from Crimea remain. But he was a Lancashire Fusilier; a youngster, I imagine very much like those young National Servicemen you can see parading at Wellington Barracks Bury today.

Except that he was probably a little man with round shoulders and bad teeth. For it is only in those huge Royal Academy battle-pieces of Lady Butler and R Caton Woodville that the British Infantryman stands six feet high, like a Trojan hero.

What happened to him, that anonymous fusilier? Did he survive that bitter Russian winter, just as he had escaped the cholera?

And the diarrhoea, the dysentery, fever, and scurvy – enemies far more deadly than the Russian bullets at the Alma and Inkerman – that swept away one man in five?

Or did he go down with frostbite?

Read the “Times” correspondent summing up the state of the British Expeditionary Force during the first Crimean winter of 1854-55:

“No boots, no greatcoats – officers in tatters and rabbit skins; men in bread-bags and rags; no medicines, no shelter; toiling in mud and snow week after week, exposed in open trenches or in torn tents to the pitiless storms of a Crimean winter.”

“Fronted by a resolute and at times enterprising enemy, and watched by the sleepless Cossack night and day from every ridge and hilltop; flank and rear encamped on a plateau which was a vast black waste of sodden earth where it was not covered with snow, dotted with little pools of foul water and stained by brown-coloured streams strewn with the carcasses of horses.”

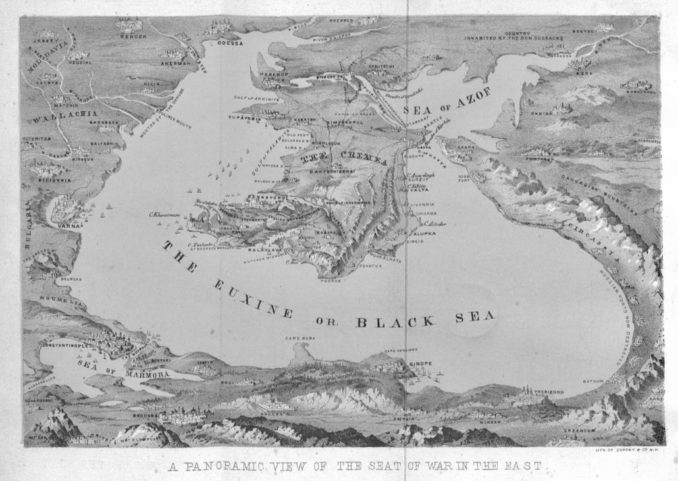

Image taken from page 10 of ‘A visit to the Camp before Sebastopol’,

The British Library – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Nowadays the Crimean War stands for no more than a weary old music-hall joke – on a par with Wigan Pier and Manchester’s weather. If we remember it at all it is because of The Charge of the Light Brigade and the Lady with a Lamp.

It is frequently dismissed by historians as the most ill-managed military campaign in British history; a campaign which, when it was all over, left nothing to show “who is the victor and who is the vanquished.”

A campaign so aimlessly conducted, so ineptly led, and so recklessly fought out that of the 4,273 officers and 107,040 other ranks sent from England to Crimea between July 1854 and April 1856, about 22,00 – or almost one-fifth of the whole force – had either been killed in action or had died of wounds or disease.

The 20th Foot – now the Lancashire Fusiliers – lost nearly 400 dead out of its total strength of 950; at one time the 63rd – now the Manchester Regiment – could muster only 30 fit men.

But if, as one historian insists, “the only celebrities of the whole campaign were an English nurse and a Russian engineer,” then the real hero of the miserable business was the anonymous British soldier.

And when, in February and March 1854, that anonymous hero began to quick-step off to a war that was to provide a great deal of death and very little glory he had not the faintest idea what it was all about.

As his country’s favourite poet was to echo only a few months later:

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to do and die.

Even now, looking back over an interval of a century, the issue still looks confused. But it seems that the nominal cause of the Crimean War was the designs of Russia upon Constantinople.

The Czar, Nicholas 1, a moody, melancholy man, wanted to see in his lifetime that great Russian Empire planned and prepared by Peter the Great.

So he contrived by various rather shady diplomatic means to establish a claim to “protect” the Christian subjects in Europe of the Sultan of Turkey.

Pintura do Czar Nicolau I por Franz Krüger,

Franz Krüger – Public domain

In 1853 he put forward demands which if accepted practically wiped Turkey off the map as an independent State.

Now neither Great Britain nor France had any great love for Turkey, but they had a very real fear of Russia, to whom popular opinion then, as now, attributed power in arms little short of invincible.

For Britain, moreover, Rumanian occupation of Constantinople meant a direct threat to the overland route to India.

Portrait of Napoleon III (1808-1873),

Franz Xaver Winterhalter – Public domain

France was less vitally affected. But she had a brand new Emperor, Napoleon the Third, opportunist nephew of the great Bonaparte, who needed a short successful war to bolster up a shaky dynasty. And so Britain agreed to support Turkey against Russian aggression, and declared war against Russia on March 28 1854.

In February when the first British troops left England, everything seemed to point to the campaign being fought out on the Danube.

In May the Russians crossed that river, starting a very gentlemanly siege of the fortress of Silistra on the 19th. Consequently, when the British and French forces first arrived in Turkish waters they were directed to Varna in Bulgaria, where thousands of them died of cholera while they were waiting for the Russians to attack.

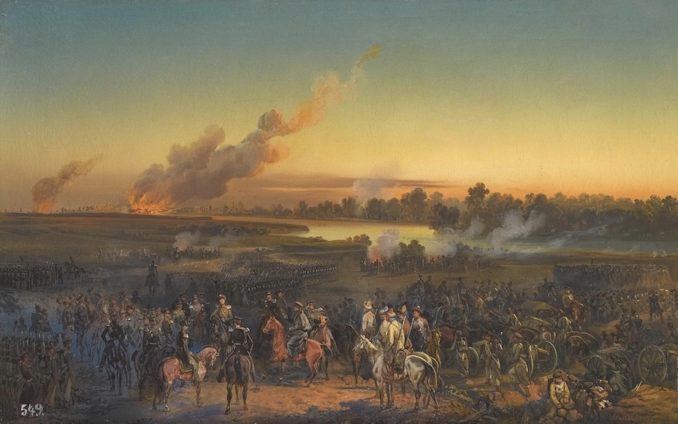

Русский: Осада Силистрии. Виллевальде,

Bogdan Willewalde – Public domain

But the Russians, as incomprehensible as ever, refused to attack. Instead, they withdrew from the provinces they had so recently occupied without a shot being fired.

Which perhaps was just as well for the Allies, already ravaged by disease and short of everything from boots to bullets.

The British Expeditionary Force ordered to Turkey was composed of five infantry divisions, each containing two brigades, and the strength of each division was about 5,000; a cavalry division of one heavy and one light cavalry brigade, three troops of horse artillery and eight field batteries.

Rather more than 25,000 officers and men all told.

With the 2nd Division under Sir De Lacy Evans, an old Peninsular soldier who had been placed on half-pay in 1818, were the 30th – now the East Lancashire Regiment – and the 47th – now the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment.

Brigaded together in the 4th Division under Sir George Cathcart, who had just been fighting Kaffirs in South Africa, went the 63rd – the Manchester Regiment – and the 20th – Lancashire Fusiliers. And marching with the 3rd Division, under Sir Richard England, a stripling of 61, were the 4th of Foot – now the King’s Own Royal Regiment.

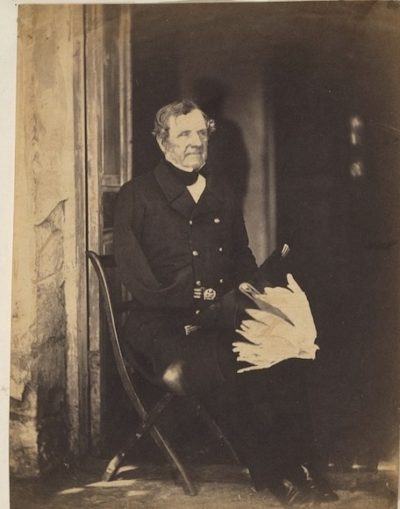

This compact and, on paper, formidable force was commanded by Lord Raglan, a courtly and polished gentleman who had fought gallantly under Wellington and lost an arm at Waterloo but who had seen no service since 1813.

FitzRoy Somerset, 1st Baron Raglan,

British Library – Public domain

The most remarkable thing about his divisional commanders was their age: with the exception of the Duke of Cambridge who was a mere 54, all were approaching 70. The most venerable of them was the Chief Engineer, Sir John Fox Burgoyne, a clever man whose advice was always reliable. He was 72 and had been gazetted into the Royal Engineers as long ago as 1798.

And as a military instrument, the army they commanded was sadly defective. Very few of the officers and men had any experience of war or even a basic training in war.

Commissions could still be bought and sold. The Earl of Cardigan, commanding the Light Brigade, entered the Army at 27, was promoted captain after only 18 months and at 33 commanded a regiment on which he spent £10,000 a year out of his own pocket

Few of Raglan’s officers, particularly those elegant young gentlemen on his staff, had any professional value. It was, as “Punch” acidly pointed out, “an army of lions led by donkeys.”

The remarkable thing is that the rank and file followed these dashing duffers so loyally.

An old sergeant of the Royal Fusiliers sums up for the “other ranks”:

“More than half the officers did not know how to manoeuvre a company, and all, or nearly so, had to be left to the non-commissioned officers: but yet it would be impossible to dispute their bravery. I have seen them lead at the deadly bayonet charges as if to waltz.”

As for Thomas Atkins, he went to war wearing a shako that fitted him like a coal-scuttle and a stock round his throat that well-nigh throttled him.

He was expected to carry on his back a knapsack weighing nearly 30lb. For his personal weapon, he was given a musket that had done good service at Waterloo 40 years before.

For although the new Minié rifle was being distributed in 1852, most units were still armed with the old Brown Bess – a ferocious weapon which kicked like a mule and was so inaccurate that on the range firing was usually practised in companies and with blanks.

Army transport he had none, beyond what he could requisition en route. His medical services and supplies existed only as book-entries.

Yet this army of cheerful, fearless incompetents was shortly to be landed in Russia, to fight an enemy whose power was entirely unknown.

‘Balaclava’ by Elizabeth Thompson, Lady Butler (1846-1933) in 1876,

Elizabeth Thompson – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Next Episode: The great Alma victory – and the Russian commander who invited a party of ladies to watch a battle from a specially built grandstand

Text:

The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

The British Library Board

© Reach PLC

Jerry F 2021