In 1969, my uncle, John Alldridge visited New Guinea to “observe the attempt to weld a primitive people to a modern society”. This is the last of his reports for the Vancouver Sun. – Jerry F

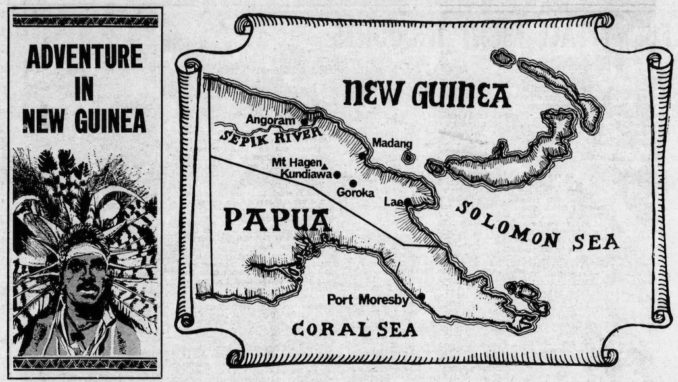

Adventure in New Guinea,

Vancouver Sun – © 2022 Newspapers.com, reproduced with permission

Madang, on the northern coastline of the territory, is considered by experts to be the most beautiful town in New Guinea.

It is built on an isthmus, and its large, enclosed harbour is dotted with palm-fringed islands and coral reefs. Coming to it straight from the steaming swampland of the Sepik I found its beauty incredible.

Madang, for me, was the end of the line. In one more day I should be flying south, over the mountains again, to Port Moresby; where that huge Qantas jet would be waiting to pick me up and fly me home in sybarite comfort.

But for a while I had had my fill of flying. In three weeks — in all sorts of aircraft big and little, I had made 21 separate flights.

It was good to get my feet on the ground. I needed time to reflect.

And cocktail hour at The Smuggler, with the evening breeze offshore, the tuna jumping, and the towering Finisterre Ranges showing their hazy peaks across Astrolabe Bay is a good place for reflection.

The Smuggler was built — literally with their own hands — by Jon Bastow and his wife Marcia.

Jon Bastow, a red-bearded Yorkshireman from Leeds, used to work in the travel department at Lewis’s before he found his way by a devious route to Madang.

He cheerfully admits that when the idea of the The Smuggler first occurred to him he had never built anything more impressive than a garden shed.

“We talked it over with the District Commissioner, bought an acre of foreshore, a brick-making machine and a few books on home design. Then we built it.”

“From the beginning we strove to create a Mediterranean rather than a South Pacific atmosphere. We wanted a cool, open place, with simple sophistication, European style.”

The Bastows have done exactly that. They have created a bit of Portofino on the edge of the Bismarck Sea.

It is a favourite place for honeymooners. There were a pair at breakfast. He was a young Australian, she a very pretty coloured girl: very shy, plainly not yet quite at home in her new high-heeled shoes.

I thought of another bride and another wedding I had witnessed a few days before in a jungle village on the road from Mount Hagen.

The bridegroom had walked 80 miles over the mountains to claim his bride; bringing

with him his friends — several hundreds of them — and a wedding gift from his village. A bullock, which would be killed and roasted and eaten at the wedding breakfast, together with great greasy slabs of fat pork and the barbecued legs of cassowary.

He was the son of a chief and she a chief’s daughter. And since this wedding was also the symbolic ending of a blood-feud which had divided the villages for generations there were wild rejoicings.

Men from both villages, terrifying in their war-paint and feathers, staged a mimic battle; stamping with their bare feet until the earth beneath turned to dust, and shrouded them in great clouds.

Then the women of the village performed the traditional marriage dance, the handful under mission influence self-consciously wearing white cotton bras. They jigged and chanted until they collapsed from sheer exhaustion.

Then the fathers of the bride and groom — fearsome figures, boar’s tusks through their noses, topping fully six feet in their bird-of-paradise plumes, and swinging long-handled axes — out-shouted each other in long, impassioned speech-making.

In the middle of this happy hullabaloo stood the bride; a plump, homely girl or so it seemed to me — eyes modestly downcast. Towering behind her, dominating everything, was a rough wooden scaffold, loaded with dozens of great gold-lip pearl shells each as big as a soup plate.

Tethered to a dozen palm trees were a score or more of scuffling squealing pigs.

Those shells and pigs worth from $5 to $10 a piece on the open market, were the “bride-price”, absolute essentials at a wedding in Stone Age New Guinea.

This is the payment a man must make to the parents of his future wife; varying in amount according to how important and how pretty she is. A price which can put a young husband in debt for years and cause endless domestic trouble; for should the marriage break-up the “bride price” must be repaid.

Some of these bride price transactions can be highly complicated.

On Manus Island a year or two ago a man paid for his wife $250 in silver coins, 3,300 dog’s teeth, 140 fathoms of Tambu shell, 300 sticks of sago, seven pigs and seven turtles.

When a primitive people learns the value of money the rackets begin. In sophisticated Port Moresby, I’m told, the price of a wife has rocketed to ridiculous levels. “Bride prices” of $1,500 to $3,000 are usual. While a 19-year-old high school graduate was bought for a record $5,400.

If a prospective bridegroom cannot find the money his in-laws will offer him “generous” hire-purchase terms. This means that many a husband spends 20 years of his married life paying for his wife.

It also means, of course, that many young New Guineans can’t afford to marry at all. The young people would like to see this iniquitous “bride price” system abolished. But the older generation would never agree to end such an ancient and time-honoured tradition; particularly those with marriageable daughters.

When a primitive people is jet-propelled towards civilization some queer things can happen …

***

Wherever I went in New Guinea I heard about the Cargo Cult — a strange confused religious belief in a Black Messiah who will return one day — in a Boeing 707 — to turn the jungle into garden land.

In his name whole armies have been drilled by cult-leaders and armed with toy rifles roughly cut out of wood. Airstrips have been laid down in jungle clearings so that the Black God’s plane can land: with dummy radio shacks and storehouses to receive the heavenly cargo — transistor radios, motor cars, television sets — the God will bring with him for his faithful people.

Caught up in a wave of mass-hysteria peaceable tribes have suddenly gone berserk and refused to pay their taxes offering themselves as willing martyrs when the police arrive.

Not so long ago there was a serious outbreak of this Cargo Cult among the island people of New Hanover, in the Bismarck Archipelago.

It began when a fanatical cult-leader said he had been told in a dream that the liner Queen Mary would arrive soon with 600 of American Negro soldiers, to overthrow the Australian administrators.

The interesting thing about this is that the people of the Bismarck Archipelago have revered the Americans ever since the war; when thousands of tons of war material were flown into their islands, as if by magic.

Six years before, in New Britain — also in the Archipelago — another local prophet claimed to have an egg with an embryo American soldier inside.

When it hatched, the American would call on his friends to take over New Britain. It took 40 police and a fly-past of Canberra bombers to quell that outbreak.

And it was on New Ireland, in 1964, that a fanatic called Bosmialek, who had worked on an American Air Force base, persuaded his fellow islanders to refuse to pay their taxes and buy President Johnson instead!

Between them the islanders actually raised over $3,000 to buy the President.

Perhaps to you this all sounds very funny. But out here in New Guinea, where a thousand tribes, as different one from another as Hindus and Hottentots, are only just beginning to struggle out of the Stone Age, these things are no laughing matter.

But among those inhabitants are some who have still to see their first wheel. There are others who eat their dead as a symbol of mourning, and many more who worship flutes and bow down before obscene idols.

In the words of Colin Simpson, a travel writer who knows New Guinea well and understands it better than most:

“Religion is here not yet transmuted into symbols. In the sacraments of the savage the communion wine is still blood.”

Reproduced with permission

© 2022 Newspapers.com

Jerry F 2023