© Maximum Overdrive 2023, Going Postal

In the cupboard to the left of my desk, sits a large cardboard box filled with old family photo albums. These arrived in my parent’s house in the early 1980s, after the death of my great aunt, and though I have looked through them from time to time over the years, they are a bit of a jumble.

Only one of them stands out as a story onto itself, a slim volume with a silhouette of a man riding a camel on the front cover. This is the only album recording a journey, although no camels seem to have been involved. The photos show only the bare bones of a story, and fleshing it out is a challenge.

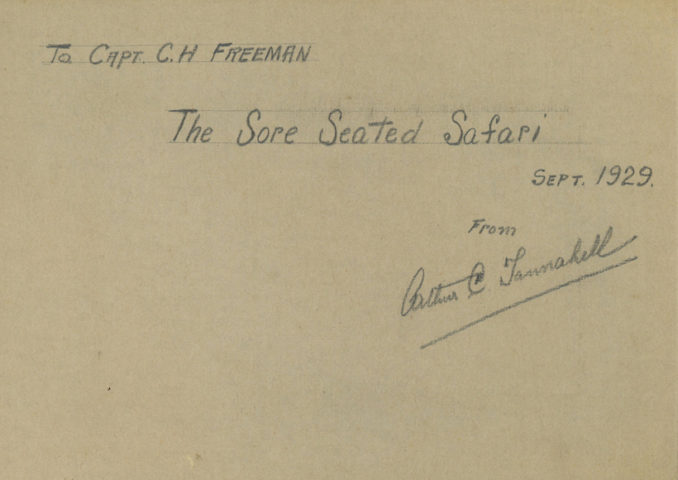

On opening the cover, there’s an inscription inside:

To Capt. C. H. Freeman

The Sore Seated Safari

Sept 1929

From Arthur C. Tannahill

© Maximum Overdrive 2023, Going Postal

Well I know who Charles Henry Freeman was. He married my grandfather’s eldest sister in 1930. He was a Lieutenant in the Royal Irish Regiment in World War 1, and I’ve discovered that he stayed in the British Army after the war, though the Royal Irish Regiment was disbanded in 1922. I’ve never seen him addressed as a Captain before though.

Moving on to Arthur C. Tannahill.

It took me a while to decipher his signature, but he has turned out to be a man with quite a bit of an online trail. Arthur Walter Alfred Claude Tannahill OBE, to give him his full title, was born in 1879, in the town of Painswick, Gloucestershire. He was schooled at Merchant Taylor’s School in London, and from 1908 had been living in Nairobi, initially working as “Inspector of Farms”, but soon gaining the title of Chief Land Ranger EAP (East Africa Protectorate).

In 1910 he married Isabella Bruce, from Scotland, and they settled in Muthaiga, Nairobi, where they had two children, Arthur Bruce, (known as Ginty), and Barbara. In 1914 he hung up his spurs as a Land Ranger, and settled down to a life of business, local government and sport. He founded Equator Saw Mills, became a director of Kenya Grain Mills, served on the Nairobi Municipal Committee for ten years, was a committee member of the Royal East African Automobile Association, and was President of the Association of Chambers of Commerce & Industry of East Africa. A busy man.

But he was also at various times President of the Nairobi Rotary Club, President of the Rugby Football Union of Kenya, and President of the Royal Nairobi Golf Club. Not to mention being the founder, Honorary General Secretary, and later President of the Golf Union of East Africa.

But back to the book.

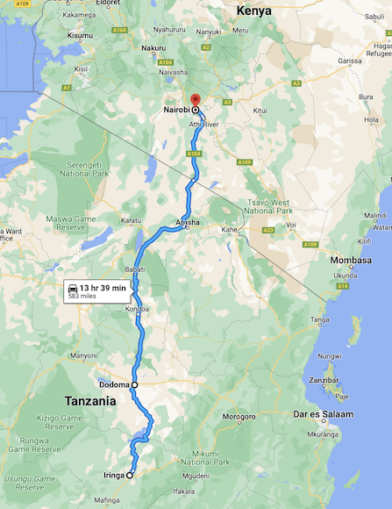

The photos in the album are mostly captioned with a date, but they are not placed in the album in chronological order, so it took a while to work out the route of this trip. It’s a journey from the town of Iringa, in present day Tanzania, to Nairobi, in Kenya. Google Maps tells me it’s a distance of 581 miles, and should take 13 and a half hours. On unpaved roads, it took a little longer. Four days.

© Google Maps 2023, Google licence

The 1929 “Brochure of the Northern Province and its Capital Town” tells us that

“Roads in Tanganyika are on the whole excellent in dry weather and certain sections even in wet weather. The sections over lava ash which disintegrates in dry weather is especially better after rains. Swampy or low-lying sections have recently had the attention of government and the work is still proceeding. Given reasonable weather conditions all important centres can be reached by road from Arusha.”

Our band of travellers are Charles Freeman, Arthur C. Tannahill, his son Arthur B. Tannahill, (known as Ginty), and a chap named Wright. I can’t find a thing about Mr. Wright, but through the magic of the internet I did find out that Ginty and Tannahill Junior were the same person, which saved a lot of confusion. There look to have been three locals travelling with them but they don’t get a name check.

The journey starts in Iringa, a town, or these days a city, in central Tanzania.

What they were doing in Iringa is unclear, but I do have some clues from other photo albums. Nothing conclusive, but perhaps a partial explanation.

The population of Iringa in 2012 was 151,345, and it’s probably a lot more now, but back in 1929 it was a fraction of that. Before the days of German expansion into what would become Deutsch-Ostafrika, the Iringa area had been the main centre of the Hehe people, the only tribe that had stood up to European incursion.

When the Germans finally defeated them in 1894, they built a large fort and the town of Iringa grew up around it. Some old guidebooks have commented on its “Bavarian“ architecture, but if it still exists, it is certainly hard to find.

© Maximum Overdrive 2023, Going Postal

Our travellers stayed at the Iringa Hotel, built in 1926 by Hugh Cholmondeley, 3rd Baron Delamere, who had moved to Kenya in 1901 and became a sort of unofficial leader of the British colony there. In 1955, in much expanded form with 24 rooms, the hotel was taken over by the “East African Railways and Harbours Corporation”, and was soon renamed as The Railway Hotel, despite being over 50 miles from the nearest tracks.

I did find a rather charming ad for the hotel from 1955 but can find no trace of the building today. It seems to have been at the current site of the Ruaha Catholic University.

From a great article by David Snowden, we get a brief description of the town and hotel in 1950, when conditions were still pretty basic.

“In 1950 my father joined EAR&H as Mechanical Inspector and we moved to Iringa – from Nairobi where he had worked for Gailey and Roberts. I remember it took nearly a week to get there. We travelled by train from Nairobi to Kisumu on Lake Victoria, then by lake steamer to Mwanza in Tanganyika, by train to Dodoma, and finally by road to Iringa. There was no house for us and so we lived, along with a number of other European families, in the Iringa Hotel for 18 months until houses were built. We had a suite of rooms at one end of the hotel but facilities were fairly basic. For example, there was no electricity in Iringa although the hotel had a generator: every evening a tractor was driven up to the hotel and a large belt was connected from the tractor’s drive pulley to the generator.”

© Maximum Overdrive 2023, Going Postal

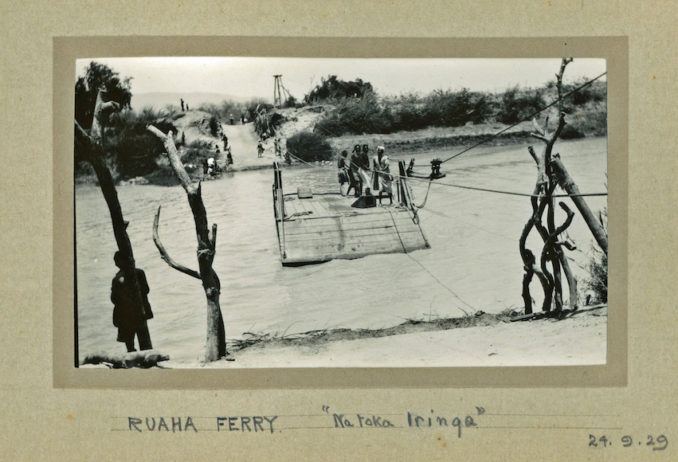

Anyway, on September 24th 1929, leaving Iringa in a car and a truck and heading north, 75 miles of winding dirt road brought them to the Ruaha river. These days it is traversed by the Mtera Bridge, which crosses a dam, but back in 1929 you had to take a ferry. One vehicle at a time and powered by five men pulling a rope. It must have taken most of the day to get there and to get across, because they camped on the north bank of the river for the night.

© Maximum Overdrive 2023, Going Postal

Long shadows in the early morning photo as they got ready for another day of bumpy corrugated roads. 85 miles to Dodoma, so an early start was needed.

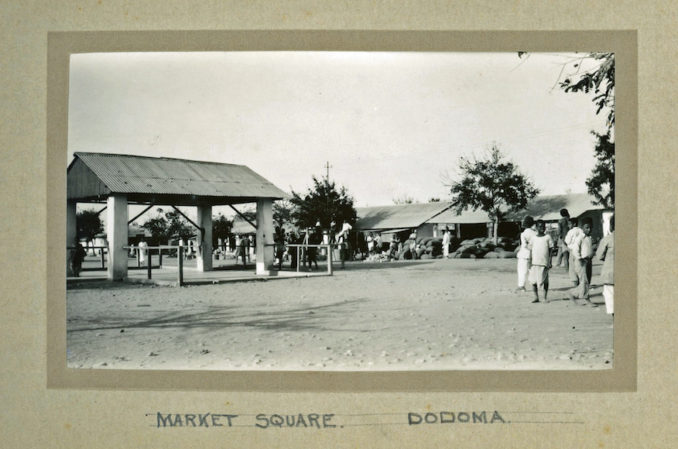

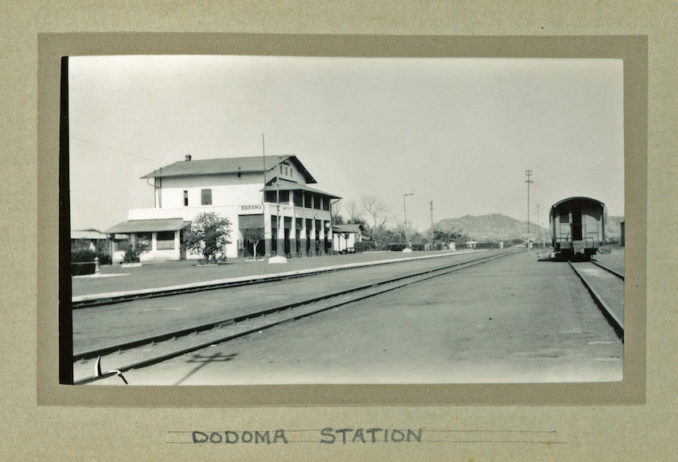

In 1907 the Germans had built a metre-gauge railway through the area and the old town of Idodomya got a station and was renamed as Dodoma.

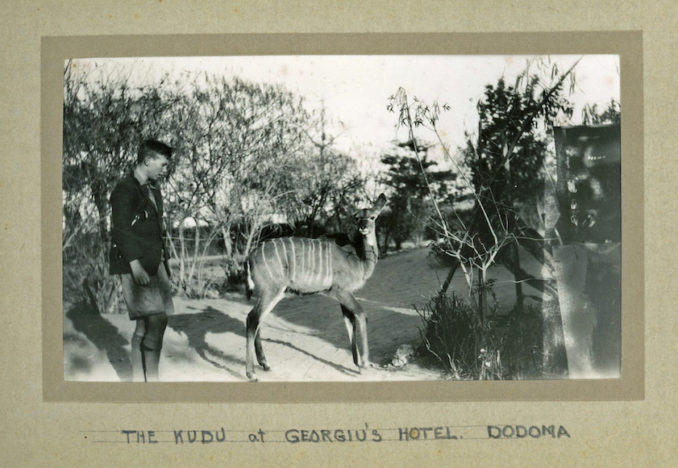

By 1929 it had grown a little, but was still a sleepy market town. Georgiu’s Hotel stood across the street from the German bahnhof. just as it does today, although Georgiu is long departed, and has left no paper trail. On a banner outside, the “New Dodoma Hotel” claims to have “120 Years of Hospitality Experience”, and has expanded quite a bit.

© Maximum Overdrive 2023, Going Postal

As has the city, for in the early 1970s, the government of independent Tanzania decided to move the capital away from crowded and chaotic Dar es Salaam, and Dodoma, being close to the centre of the country, was chosen as the new capital city, a mantle it officially donned in 1996. Many government offices and embassies have resisted this move however, and Dar es Salaam does remain the commercial centre of the state, but the population of Dodoma has grown past 200,000 in the city itself, and past 2 million in the surrounding region.

© Maximum Overdrive 2023, Going Postal

The tin-roofed German railway station stands much as it did ninety-four years ago, but not for long. Tanzania is currently replacing all its metre-gauge lines with standard gauge, laying new track parallel to the old. There seems to be quite a bit of Chinese involvement. Dodoma’s old station building will be supplanted by a large brutalist structure, already under construction, which looks like something from a 1970s sci-fi film.

© Maximum Overdrive 2023, Going Postal

Our merry band must not have stayed long in Dodoma though. Just a pit stop. They’d cover a lot of ground this day. Next stop, Kondoa Irangi.

I’ll let Henry Anthony Fosbrooke set the scene, from an article he wrote for Tanganyika Notes & Records magazine in 1952…

“Kondoa Irangi, as many travellers know, lies 100 miles north of Dodoma and two miles west of the Great North Road. Kondon, or Mkondoa, is the name of the river which runs through the station and Irangi that of the surrounding tribal area. It is not known how the double name arose. Till the latter half of the nineteenth century the surrounding area is said to have been thick miombo forest when two Irangi tribesmen, attracted by the never failing and abundant water supply, cleared holdings for themselves. They were shortly followed by Arab ivory traders with attendant native hunters, mostly of the Makua tribe.

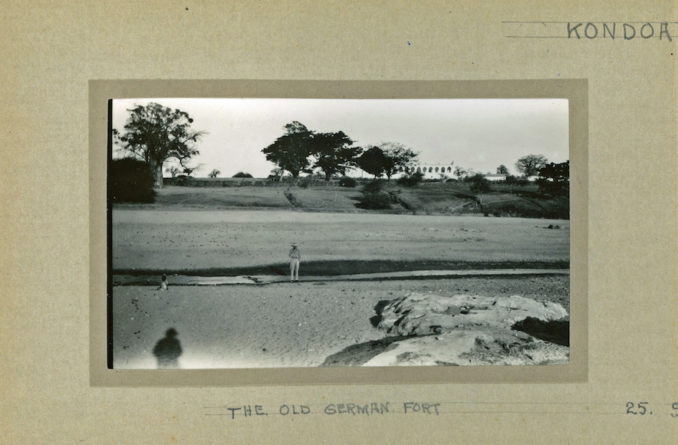

“The first published reference that can be traced is in Karl Peters “New Light on Dark Africa”, English Edition, 1891, where he states of a certain Arab: “He possessed places of business in Irangi and was now following his caravan thither for the purpose of sending the ivory stored up there to the Coast”. The Germans shortly followed and there is a record of a Herr Brekman (Junior Officer) in 1897 and of Lieutenant Bomstack and Ober-Lieutenant Bomolah being stationed at Kondoa in 1898. In 1906 Medical Police and Veterinary officers were posted there and the town was laid out as a model up-country station which developed into the headquarters of a district more than twice as large as now, extending from and including Mkalama in the west and Kibava in the east. It was also a big military centre, the troops being housed in a fortified cantonment of which little remains except the double-storeyed officers’ quarters which now comprise the District Head Quarters…

“Another point of interest is the absence of a roof from the present boma when the aerial photo was taken about 1932. This was the result of the scorched earth policy of the Germans when threatened with capture by the British in 1916. I have been lucky enough to contact Mr. Frank Green who was in the van of the advance: he most kindly gave the following facts.

“The Fourth South African Horse were first into Kondoa with the 2nd and 4th Battery of the South African Field Artillery, Mr. Green’s unit. The force comprised some 512 men who advanced down the old Kolo road through Bolisa, firing over open sights at the retreating Germans. On arrival at Kondoa they found the building which is now the boma on fire: burning rice and other stores filled the ground floor rooms, the ceiling had gone and the roof timbers were burning. In consequence of which the corrugated iron sheets were sagging in.”

© Maximum Overdrive 2023, Going Postal

Indeed the “boma” appears to be without its roof in our photo. Judging by his hat I think that’s the elusive Mr. Wright standing by the dried up river bed, and judging by the shadow of the photographer it is quite late in the day.

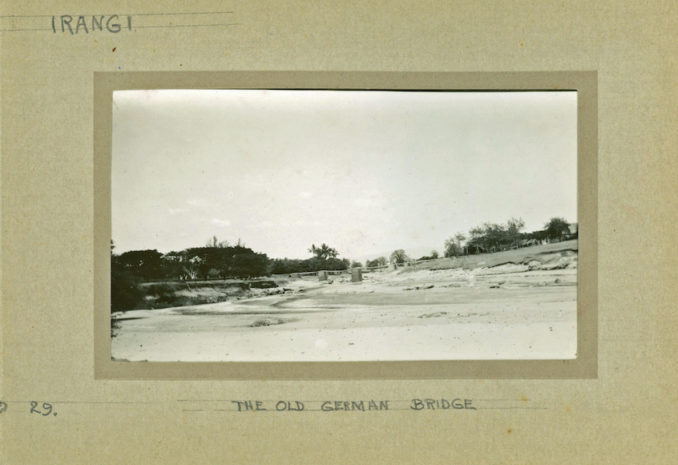

At this time there was only a footbridge over the river, so they were in luck that there was no water flowing.

Indeed even as late as 1958 there was no road bridge here.

© Maximum Overdrive 2023, Going Postal

“Administrative Officer”, Charles Cullimore’s account of moving to Kondoa in 1958 with his family is so good that I have to include it. By this stage the old boma had been re-roofed and was used as the headquarters for the British local government.

“In August 1958, together with my wife and 17-month-old daughter, I disembarked from the Union Castle liner “Kenya Castle” in Dar es Salaam. We left the ship with some relief for it had been a very hot passage through the Suez Canal and the Red Sea with no air conditioning in the cabin. After a week in Dar for briefings and a round of calls on officials including the Governor, I was posted to Kondoa Irangi in the Central Province. We took the weekly train on the old German-built railway line as far as Dodoma and then travelled on by Land Rover over a hundred miles of dirt road to Kondoa, with all our belongings following in an open government truck.

“Kondoa at that time consisted of a small trading centre on the far side of a sand river partly inhabited by descendants of Arab slave traders. On the near side stood the District Office of Boma, a magnificent white Beau Geste style fort with a crenellated tower built by the Germans. The two sides were linked by a somewhat precarious suspension footbridge. On the same side as the boma there was a scattering of a few European style houses.

“As a very junior District Officer cadet I was allocated a simple mud brick house with three inter-connecting rooms and a corrugated iron roof. We later added a concrete platform to walk out on. The kitchen was in a separate thatched hut with a wood-burning “Dover” stove. We had the luxury of piped water from a tank further up the hill. The water could be heated by firewood in a “Tanganyika boiler” – an open 44-gallon drum attached to the outside of the house. There was no electricity and the only communication with the outside world was via a radio transmitter in the boma for half an hour a day. But we had pressurised oil lamps for light and a very efficient paraffin fridge. We also had a Deccalian record player powered by the car battery for entertainment, plus a young orphan rhesus monkey and a large chameleon.

“Shortly after my arrival the District Commissioner asked me to go and arrest five Masai warriors who had rustled some cattle from their local Warangi owners. Such events were not uncommon as the Masai had the convenient belief that God had given all the cattle in the world to them, and Kondoa was on the edge of Masai country. Accordingly I set out in the government Land Rover pick-up with a local messenger from the boma. The borehole where the Masai were reported to be watering the cattle was about 40 miles east of Kondoa. As this was only a one day safari I decided to take my wife and daughter along for the ride.

“On arriving at the borehole we found five tall Masai warriors standing near it with their spears and the cattle. As we approached them they formed a circle around our tiny blonde-haired daughter and, to our horror, began spitting on to her head. Our concern was allayed somewhat when the messenger explained that this was a traditional form of blessing. We later discovered that she was the first white child these Masai had ever seen.

“Despite their gesture of goodwill, I then had to tell the messenger to explain to them that they were being arrested for stealing cattle and that they should get into the back of the pick-up. It never occurred to me that they might simply have refused or indeed that they might have disputed the allegation that the cattle were in fact stolen. More importantly, and fortunately for us, it never occurred to them either. Had it occurred to them to resist arrest there was absolutely no plan B. They could simply have disappeared into the Serengeti and our tiny African police force in the district could not have found them even if they had tried. In the event they climbed happily into the back for the journey to Kondoa where they subsequently spent a few weeks in “Her Majesty’s Hoteli” as the local prison was known in Swahili.

“Looking back it seems to me that this small episode illustrates how, in Tanganyika at any rate, British rule was dependent on the willing support, or at least acquiescence, of most of the people. Without that it would not have survived.”

As noted the sun was casting long shadows, but our travellers were still going to hit the road again. Travelling these roads after dark was probably not advisable back in 1929, so it’s unclear why they didn’t stay in the town, but crossing the riverbed they headed north once more. About 15 miles out of town are the ancient rock paintings on cliff walls for which the area is now famous, but then again, these weren’t really known by white men until anthropologist T. A. M. Nash discovered them that same year, 1929.

It must have been dark when they arrived at Bereku, 37 miles north of Kondoa. Maybe that was for the best, as they surely would have picked somewhere better.

Eleanor Rushby, writing about a 1945 journey in the opposite direction, also had to stay in Bereku, and possibly even stayed in the same place…

“It had been our intention to spend the night at the furnished Government Resthouse at Babati but when we got there we found that it was already occupied by several District Officers who had assembled for a conference. So, feeling rather disgruntled, we all piled back into the lorry and drove on to a place called Bereku where we spent an uncomfortable night in a tumbledown hut.”

To be continued…

© Maximum Overdrive 2023