“In the second of his articles from North Africa, where he is re-covering the ground of the war in Tunisia, John Alldridge revives memories of the 600-mile railway journey between Algiers and Tunis. The railway track passes through a terrain hostile and unfriendly to man — but also historic in memory.” – Manchester Evening News, November 10 1949

Tunis, Wednesday

The last time I travelled from Algiers to Tunis I went by rail. It took four-and-a-half days to cover 600 miles.

This time I travelled by Air France. It took three hours.

But I have vivid memories of that rail trip nearly seven years ago.

A French engine, an Arab fireman, and an American engineer. Six officers to a very old and unhygienic French first-class carriage, 25 men to a box-car.

But it was by no means a monotonous journey. There was plenty to pass the time.

First thing every morning you hunted shy bugs out of the seat upholstery with a candle flame.

You drew hot water from the engine and shaved beside the track.

You “brewed up” in a 25lb. biscuit tin, using the Army biscuits as kindling; and you strained the precious tea through a strip torn from your mosquito net.

You cooked on the carriage floor on a Tommies’ cooker held between your feet — a savoury mess of tinned beans and eggs bought from the Arabs, who ran beside the train all the way and were a bigger pest than the bugs.

At night you made a brazier out of a biscuit tin and hung it outside the truck. So that a long line of blazing beacons turned the slow-moving train into a convoy of covered wagons crossing the Western prairie.

You smoked and you sang songs you hadn’t sung since you were a child. Then you lay rolled up in your blanket, watching the wheeling stars through the open roof of the box-car.

Somewhere far away a jackal howled.

The man beside you was snoring gently.

You were strangely content and you found yourself wishing that this journey could go on for ever.

The future was so dreadfully uncertain. And here for a little while you could lie and think, and dream, and remember undisturbed.

There was one scene in that journey that stands out in my memory above all others. I can almost relive it again today.

We stand by the train and look at an outhouse beside the battered railway station.

The outhouse has taken a direct hit. One cannot read the name of the station.

Beyond the station the Tunisian plain, bleak, sparse, stretches away to some cruel peaks.

Men, glad to get out of their box-cars, curious as monkeys, are picking up unexploded grenades, empty mortar-bombs, boxes, shell cases, that lie in great rusting heaps.

The young Scot who joined us in the night and who hasn’t said a word so far, suddenly comes to life.

He points to the ruined out-house.

“That must have been our company cookhouse,” he says.

And his voice has the tired, uncertain note of an old man who is trying to remember.

Yet he cannot be more than 23.

“Yes, that must have been the cookhouse. March 3, last year, it was. They were cooking breakfast when Jerry started shelling. You can see his Observation Post, that red-roofed house on the crest to the left. Only we didn’t know it then. I often wondered what happened to that breakfast.”

He turns his back to the station and walks across the line.

“We put in an attack over there by that little mound. A pretty bad show.”

We look at the country over which the Argylls attacked that morning. And shuddered.

Not so much as a blade of grass for cover. Yet the Argylls took the crest — took it and held it.

They were English boys many of them, charging to the skirl of Scottish pipes.

“You can see the cemetery over there, half-right.”

We can see it quite clearly. The headstones stand up in neat, soldierly rows, like the Argylls on ceremonial parade at Stirling Castle.

Beyond the cemetery are the ruins of a Roman fort. They buried their dead here, too.

The French engine works itself into a fit of hysterical frenzy. The Arab fireman spits over the side. The American engineer languidly shrills his whistle…

A German tank lies burnt out on its side. Thistles sprout between its rusted tracks. Where it churned up the ground in its dying agonies spring grass is growing.

Out on the plain a lonely cross has fallen over. A bird is nesting in a dented helmet.

Nowadays Air France allows you a 10-minute halt at Bone.

You get down and stretch your legs on an airstrip that the R.A.F. scratched out of the middle of nowhere and left behind as a parting present.

You can still see where the dartboard hung in what used to be the sergeants’ mess.

You get back in the plane and you doze and yawn and yawn and doze while Tunisia unfolds below you.

First, mile after mile of salt marsh and swamp. Then on over a barren featureless country of defile and gorge and deeply furrowed hills.

It is a country of few rivers and fewer roads — a hard country to live in, an impossible country to fight in you would think.

But it was into this unknown country seven years ago that the First Army chased like a pack of eager and untried hounds.

Alan Moorhead who followed hard after them as an official war correspondent wrote at the time, “American Rangers and men of their best command team, British parachutists, battle-school-trained infantry from the British Seventy-eighth Division and the Sixth Armoured Division — these were the men who raced forward into the unknown mountains.

“They commandeered civilian cars, got the railways working, reopened the telegraph branches, took over farm houses as hostels, and cleared the roads.

“And always they hurried forward ward until their supplies were stretched to snapping point and unpoliced territories the size of half England were spread out behind them.”

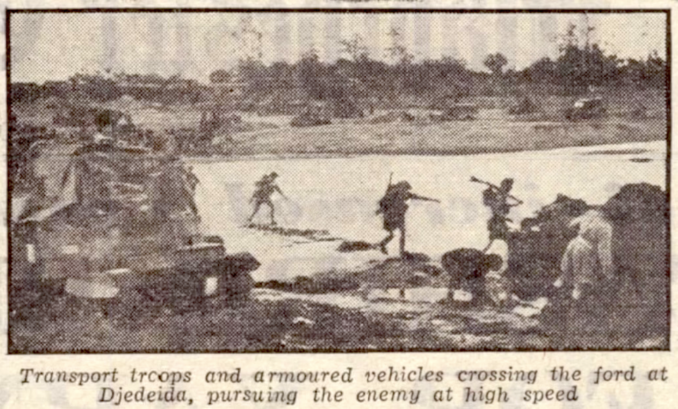

For one dazzling, delicious moment it looked as if the gamble would come off. By November 25 the 78th Division had reached Djedeida. Tunis their final objective, lay barely 12 miles away up the valley.

Transport troops and armoured vehicles crossing,

© 2024 Newspapers.com –

Already their patrols could look down on trim, suburban villas.

Then in that moment the pendulum began to swing the other way. The Germans reinforced, counter-attacked — and rain — the torrential, persistent, African rain fell.

And the long drawn-out struggles for Tunis had begun.

But that was seven years ago. Just now you are tired. Your head aches.

And paunchy, near middle age, you begin to wonder whether dinner at the Tunis Palace will be as good as it was at the Oasis in Algiers last night and whether they can find you a room with a bath.

Reproduced with permission

© 2024 Newspapers.com

Jerry F 2024