We shall continue our trip towards the source of the Matter Vispa, heading south towards the mountain town of Zermatt. However, we shall no longer call it a road trip. The evidence suggests, given a difficult road then and now, that my grandparents left their intrepid Ford Prefect at the chalet in St Niklaus and proceed by train along the Brig-Visp-Zermatt-Bahn. In the modern day, the seven-platform terminus is a disappointing u-boat pen of a concrete box – albeit avalanche-proof – tucked into the hillside. Alongside sits further insurance against a collapsing winter hillside – a deep man-made trench.

At right angles lies another depressing slab-sided terminus, that of the Gornergrat rack and pinion railway which winds its impossible way to the top of 10,000 ft elevation Gornergrat ridge, with its spectacular westerly views of the Matterhorn and a second’s-loss-of-concentration tumble onto the glacier below. A Bond villain building with an observatory at each corner sits there, taking advantage of crisp, light pollution-free Alpine air.

It was not always so. When my grandparents alighted from the train seven decades ago, a traditional pitched and latticed station canopy protected a tabac stall and gave shelter to the country end of a queue of porters dispatched from nearby hotels. Meanwhile, on the station square opposite, horse-drawn coaches awaited tourists, walkers and mountaineers (amateur and professional alike) and their luggage.

© Always Worth Saying 2023, Going Postal

© Always Worth Saying 2023, Going Postal

Left to right we can see a horse-drawn taxi for the independent traveller alongside the liveries of the Hotels National Schweizerhof and the Grand Hotel Montcervin (another name for the Matterhorn). In the background, a partly obscured sign on a gable end reveals ‘rgrat’, for the Hotel Gornergrat, still there today but now a disappointing redeveloped brutalist concrete stump. Likewise the Place de Gare itself, these days a concrete and glass lower story with outsized Swiss chalets plonked atop as if a 1970s Scottish new town shopping centre.

There was previously a more romantic but dangerous age. Until the late 19th century Zermatt was an agricultural village of a few hundred hardy farmers struggling to extract a living from the meadowland or ‘matten’ at the valley floor. Hence the name: Zur for ‘at’ and Matte for ‘meadow’.

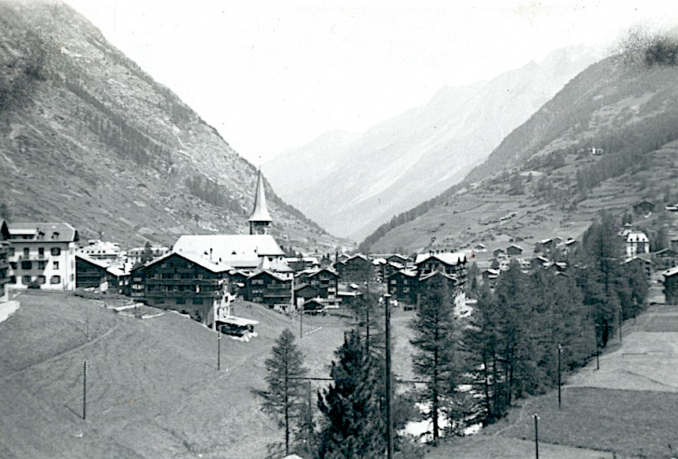

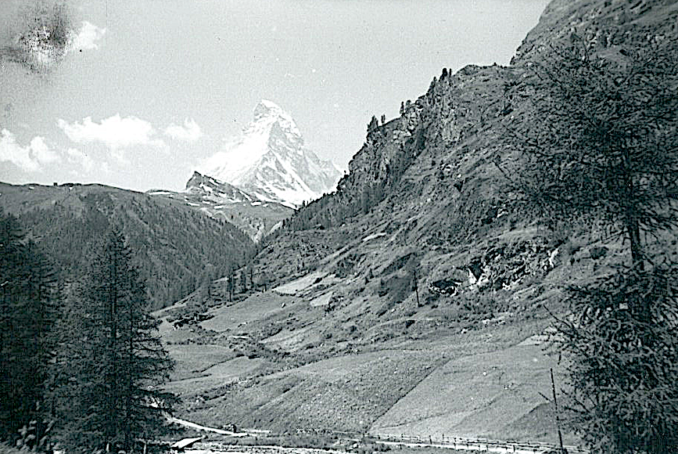

During my parent’s 1950s visit, it was still possible to take an unobscured view of the township and the parish church of St Mauritius when climbing the footpath south of the Mattar Vispa en route to Findelbach. Nowadays the hillsides are covered in chalets, mostly apartments for tourists. But in the other direction, then and now, sits clearly the mighty Matterhorn, at 14,692ft the sixth highest peak in the Alps and the last to be conquered by mid-19th century hardy gentlemen explorers.

© Always Worth Saying 2023, Going Postal

© Always Worth Saying 2023, Going Postal

Discovered firstly by British Alpinist mountaineers and subsequently in the wake of their adventures by all and sundry, Zermatt may have remained little disturbed at the end of its anonymous valley had it not been for a tall tale of derring-do, if anything even more adventurous than driving from Carlisle to the Alps in a Ford Prefect.

The Journal de Geneve of the 16th of July 1865 contained the following intelligence:

“It is well known that among the peaks of the Swiss Alps which are reputed to be inaccessible, Mont Cervin, or Matterhorn, holds the first place, and hitherto, owing to its pyramidal form, it has resisted all attempts made to climb it. However, one of the most learned and intrepid tourists of England, Professor Tyndal, had sworn, so to speak, to succeed. We fancy at least that it is to him we are indebted for this very brief dispatch that we received yesterday from the Hotel du Mont Rose, Zermatt:- ‘The expedition which left on the 13th July arrived at the summit of Mount Cervin on the 14th July.’ We hope to have details soon of this fresh effort of human energy and will.”

However, within days the London papers were carrying the following:

It would seem that although according to the above dispatch the ascent was successfully accomplished, the descent was attended by a sad casualty. A telegram, dated Berne July 18, received at Mr Reuter’s office on Thursday, is thus worded:- “The Berne papers announce that three English gentlemen lost their lives while descending the Matterhorn, in the Canton Valais, on the 14th instant. Their names are stated to be Lord Francis Douglas, the Rev Mr Hudson, and Mr Haddo.”

The morning of the 13th July 1865 had begun well. At 4:30 am start from Zermatt saw a combined party of seven men led by Edward Whymper, aware that they were in competition with an Italian expedition, set off for the Matterhorn under a clear sky. Whymper, young Lord Francis Douglas, Charles Hudson and Douglas Hadow, a Zermatter called Taugwalder and his two sons, and mountain guide Michel Croz, climbed past the Schwarzsee to a plateau where they camped. Meanwhile, the Italians, led by Carrel, had camped at a height of about 4,000 meters on the Lion Ridge. On 14th July, Whymper’s party proceeded, minus one of Taugwalder’s sons who had returned to Zermatt, to a successful first ascent by the Hörnli route.

However, the omens were not good. Reflecting upon subsequent events in Nantes’ Semaine Religieuse, a M. Edouard de Kersabiec quoted an ‘impeccable source’ who spoke highly of Lord Francis Douglas as a serious and religious young man of much promise, taken by his mother’s conversion to Catholicism. Francis even followed the Catholic mountain guides to Mass regularly on Sundays.

Ominously, upon reaching the summit Lord Francis announced himself frightened and confided to his companions, ‘Gentlemen, there is great reason to fear that we may not be able to effect our descent without an accident; therefore, let each of us think about his soul.’ Mr Hudson, a Protestant minister, took out his Bible and read. Lord Francis went apart from the others and remained in silent prayerful meditation for a full hour. On the same day, according to M.de Kersabiec, his mother, the Marchioness of Queensberry, was in her garden on the Isle of Wight when she experienced a student revulsion of the heart feeling her son was in danger. She appealed in prayer to his guardian angel.

For three days she was struck with the thought that he was dying of famine. At the same time, one of the marchioness’s pious maids took a vision of a young man covered in wounds approached by a monk holding out a radiant cross which the young man kissed before expiring.

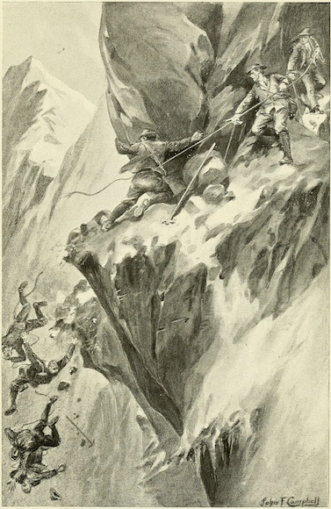

In his book of the expedition, Whymper described the fateful events that led to catastrophe while the roped-together men descended from the summit.

Michael Croz had laid aside his axe, and in order to give Mr. Hadow greater security was absolutely taking hold of his legs and putting his feet, one by one, into their proper positions. As far as I know, no one was actually descending. I can not speak with certainty, because the two leading men were partially hidden from my sight by an intervening mass of rock, but it is my belief, from the movements of their shoulders, that Croz, having done as I have said, was in the act of turning round to go down a step or two himself; at the moment Mr. Hadow slipt, fell against him and knocked him over.

Mr Whymper heard a startled exclamation from Croz and then saw him and Mr Hadow flying downwards, with Hudson then dragged from his steps followed by Lord Francis Douglas. All this occurred within a single moment. Immediately upon Croz’s exclamation, Wymper and old Peter Taugwalder planted themselves firmly upon the rocks. The rope connected them to the falling men became taught, jerked and then broke between Taugwalder and Lord Francis. For a few seconds the falling men could be seen sliding downward on their backs endeavouring to save themselves until they fell from precipice to precipice and onto the glacier four thousand feet below. For an hour, Whymper and Taugwalder remained clinging to the spot, unable to move a single step.

Daring deeds of great mountaineers,

Richard Stead. Public domain

A brief and unsatisfactory inquest followed in Zermatt. The coroner was a local hotelier who asked few questions, none of them searching. Back in England, controversy raged, the suspicion being that the rope had not snapped but was cut so that the senior mountaineer and his guide might save their own lives. Speculation was heightened as only three bodies were found. There was nothing discovered of Lord Douglas apart from his unlaced boots.

In his article, M. de Kersabiec speculated Lord Francis Douglas had fallen down a crevasse and survived the fall but, guardian angel or no guardian angel, perished there of hunger.

By August 2nd 1865, a brother of Lord Francis Douglas had arrived in Zermatt for the purpose of discovering his remains. He offered a large sum to anyone who could find the body before starting out alone for the Matterhorn pursued by two guides sent after him to stop the pointless quest before further tragedy.

***

Four decades later, the London offices of The Times newspaper received an envelope containing a telegram pinned to an accompanying letter scripted by an elegant and noble hand. The telegram read:

“Geneva, Sunday April 9th – there is every possibility that the body of Lord Francis Douglas will be delivered up by the slowly moving glacier this summer. It is forty years since the terrible accident occurred by which Lord Francis Douglas lost his life during the first ascent of the Matterhorn. Despite prolonged search, no trace of the body of Lord Francis Douglas could ever be found. In the past 40 years, however, the Zmutt glacier has been descending regularly and rapidly, and, according to natural laws, the portion of the glacier where the Alpinists fell should reach this valley this year. The body will be in a perfect state of preservation, and easily recognisable.”

The accompanying letter, signed by Lady Florence Dixie, continued the tale,

I was a very little child when the accident occurred, but I recall the fact that my brother expressed a wish before leaving for the Alps that if he should be killed, and his remains recovered, they should be buried on the spot. I shall take every step to ascertain if my brother’s body is yielded up to the glacier, and this is to ask the kind cooperation of anyone who may be in those parts, who can greatly assist by keeping a sharp lookout for the long-lost body and wiring information to my solicitor, Charles Stewart, Esq. 57 Coleman Street, London, E.C.

Mr Stewart’s desk remained untroubled. Lady Florence waited in vain. Although a tragedy for all concerned, it was the fate of Lord Francis which, then and now, captured the public imagination. Lord Francis William Bouverie Douglas was the son of Archibald William Douglas, 8th Marquis of Queensbury and the brother of John Sholto Douglas, 9th Maquis of Queensbury whose Queensbury Rules form the basis of modern boxing. Only 19 when he perished on the Matterhorn, Lord Francis was educated at the Edinburgh Academy and was an uncle to Oscar Wildes’s squeeze, Lord Alfred Douglas.

As for sister Florence, she married happily but badly. Husband Sir Alexander Beaumont Churchill Dixie, 11th Baronet Dixie (known as A.B.C.D.) was the fool who lost the country estate at Bosworth Hall through drinking and gambling. Apart from the choice of husband she did rather well, becoming a renowned writer, traveller, war correspondent (in situ for the Boer war on behalf of the Morning Post), President of the British Ladies’ Football Club and High Sheriff of Leicestershire.

With no grave for her brother Lord Francis, a memorial stands on the outer wall of the Douglas family mausoleum at Cummertrees, near Dumfries. The inscription reads:

Sacred to the memory of Francis William Bouverie Douglas Aged 19 who was killed on the 14th July 1865 in descending the Matterhorn after his successful ascent. His body was never recovered.

There – stars will ever shed their light.

The sun will gild each rising morn:

His winding sheet – the glacier bright

His monument – the Matterhorn

Not lost but gone before

“For I know that my redeemer liveth, and that he shall stand at the latter day upon the earth: And though after my skin worms destroy this body, yet in my flesh shall I see God:” – Job XIX 25-26

© Swiss Bob 2023, Going Postal

© Always Worth Saying 2023