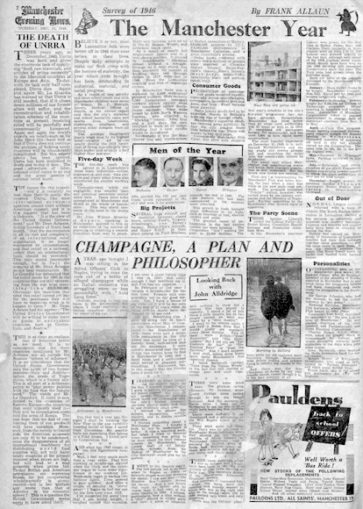

On New Year’s Eve 1946, my uncle reviewed his first year at home since the end of the War for the Manchester Evening News. It would seem that at times he was finding it hard to readjust – Jerry F

© Reach PLC, Going Postal

A year ago tonight I was sitting in the Allied Officers’ Club in Naples, trying to coax the cork out of a bottle of alleged Champagne while an Italian orchestra was struggling more or less successfully with “Auld Lang Syne.”

Outside, waiting to run me home to the six-roomed flat where I lived rent-free, my Italian chauffeur dozed over the wheel of my car.

Yes, that was a year ago. Tonight I shall be toasting the New Year in the one carefully hoarded bottle of beer I saved from Christmas. My marble halls are something that belong in a fitful dream. I travel now by Corporation bus.

And what has 1946 meant to me, one Manchester rate-payer?

Well, I feel very much more than a year older. That first warning of middle-age started when the clock and the calendar began to have some significance in my working life. Week-ends began to beckon like harbour lights. Time seemed to pass quicker. And after a couple of months in “civvy street” I began to feel my age for the first time since 1939.

I’ve suspected for some time that I am losing weight. I weighed myself this morning. I am over a stone lighter than I was in 1945; and oddly enough I feel healthier for it. But I’ve lost my appetite. . .

In February of this year I became a householder for the first time. Friends still congratulate me on my good fortune. Yes, I have a house of my own – or it will be my own at the end of 21 years when its value will no doubt have decreased by 50 percent.

Oh, yes. Something else. I gave up going out to lunch somewhere about May or June. In the Manchester I remembered – the Manchester of 1939 – there were half a dozen little restaurants in the city where you could be sure of a homely meal, well-served and not too expensive. I very quickly discovered that the two things you cannot hope to find in Manchester in 1946 are a hotel room and a well-cooked meal served in pleasant surroundings.

I learned to brace myself for the nightly battle for the bus. I learned patience. And I grew to admire the patience of my fellow citizens. But none of my newly-acquired patience could make me understand why the city’s busiest transport services should begin and end in one relatively small area.

I learned to admire bus drivers, housewives, school-masters, and to dislike seaside landladies.

I learned something about a Manchester Plan. I bought a book to try to understand it better. It was a beautiful book. But when I tried to discover when something was going to be done about the most hideous eyesore in Manchester, the ruined shell of All Saints’ Church, nobody, from the Bishop of Manchester to the City Surveyor, could give me an answer.

I went to the theatre again. The last curtain fell at an hour when in Naples or Paris or Brussels people were just dressing for dinner. I saw one play – “The Winslow Boy” – which moved me rarely. And I saw others that were no better and no worse than I had seen at the same theatre in 1939. I noticed, particularly, how a play without a star played to empty seats and how a piece of nonsense with nothing to show but a famous film face played to capacity. I heard a lot of talk about a civic theatre, but no two people agreed on what was meant by “civic theatre”.

I went to the cinema again. I saw half a dozen films that I would gladly see regularly every three months. Two them were British – “Brief Encounter” and “The Overlanders.” But I did not see “Les Visiteurs du Soir” or “The Turning Point” or “Ivan the Terrible.” And I don’t suppose I ever shall, unless some brave spirit opens Manchester’s first repertory cinema.

I heard Barbirolli conduct “Tales from the Vienna Woods” in the hall that still smelled of orange peel and stale cigar smoke.

There were some good days. The glorious spring afternoon, for instance, when Lovely Cottage came racing through to win the Grand National. And the morning in March when I went out to Mobberley to see the site of what might have been our first satellite town. There were daffodils in the churchyard and a philosopher of the Will Rogers school in the smithy.

There were some bad days, too. There was an afternoon in Manchester Royal Infirmary when they showed me the meagre supplies of blood donated by Manchester volunteers. And a morning in Salford after the floods had drained away and there was nothing left but slime and dumb despair.

There were evenings when I was so content that I might have been back in ’39. My first glimpse of olde tyme dancing at Belle Vue. The centenary dinner of the Manchester Athenaeum Dramatic Society.

And evenings of frustrated fury – when the buses were not running and nobody seemed to know who was in the right and who in the wrong – when life in 1946 seemed very bleak and very desperate.

There was the October afternoon when my old regiment went marching through Manchester with drums rolling and colours flying to receive the thanks of the city.

And there was the first Christmas at home by my own fireside which, recent though it is, is the best memory of all.

Text and Image:

The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

The British Library Board

© Reach PLC

Jerry F 2022