In an earlier piece, I mentioned the Trent and Mersey Canal, with its company headquarters in Stone, hinting that its history and the political shenanigans behind its construction might be worth an article in its own right. This, as you may have guessed, is it.

But before we dig too far into detail and dirty deeds, it’s worth checking the definition of a ‘canal’, which The Cambridge Dictionary describes as:

“a long, thin stretch of water that is artificially made either for boats to travel along or for taking water from one area to another”

Thus, somewhat different to an existing river, adapted in some way to allow for boat traffic. Now, some folks might have you believe that canals originated in China with the construction of what eventually became the Grand Canal, a UNESCO World Heritage Site rivalling the Great Wall in magnitude. Otherwise known as the Jīng-Háng Dà Yùnhé, this canal is pretty impressive, running 1,104 miles from Beijing in the north to Hangzhou in the south. It links five of China’s major east-west rivers: the Hai, the Huai, the Yangtze, the Qiantang, and the Yellow Rivers, as well as many smaller natural waterways. The Grand Canal is certainly the longest man-made waterway in the world, but is it the oldest? Let’s see.

Nope. In fact, mankind has been building canals for a very long time. Whilst modest, seasonal irrigation channels almost certainly predate them, the first permanently constructed and maintained canals were likely relatively small affairs, cut between the Euphrates and the Tigris Rivers by the Mesopotamians (in fact, ‘Mesopotamia’ means ‘the land between the rivers’). There were a number of these, completed around 4,500-3,100 BC in the Fertile Crescent to control the waters of these great waterways for irrigation.

Over time, people started building larger canals, eventually building and using them specifically for trade and the transportation of goods. An important example, forerunner of the Suez Canal, was created by the ruler of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian emperor Darius the Great (Darius I), about 520-510 BC.

Linking the Nile and the Red Sea, this was the ‘Canal of the Pharaohs’, and it was no minor project. It was said by Herodotus, the ancient Greek historian and geographer, to be wide enough for two triremes to pass each other with oars extended. As triremes were typically about 115 feet long and 60 feet wide, including the oars, that must have been quite a sight to see.

Tyler Bell, licensed under CC BY 2.0

Thus, the practice of canal building pre-dates all but the preliminary stages of China’s Grand Canal by quite some margin. Its oldest section, established sometime in the 6th century BC, was constructed in the Yellow River Valley’s ‘Cradle of Chinese Civilization’, the ancient breadbasket of China. This first section was the Hong Gou Canal (Canal of the Wild Geese), which linked the Yellow River near Kaifeng in Henan Province to the Si and Bian rivers. The next section to be built, the Han Gou Canal, linking the Yangtze River to the Huai River, was completed around 480 BC. However, it wasn’t until around a thousand years later, c. 604-609 AD that these two ancient canals were extended to fully complete what we now know as the Grand Canal.

Meanwhile back in Britain, some considerable time before the Grand Canal was completed, the Romans (what did they ever do for us, eh?) were being busy boys. Having embarked on canal building projects back home in Italy in the 2nd century BC, they were at it in Britain by the 1st century AD, linking rivers such as the Cam, the Ouse, the Nene, the Witham, and the Trent.

At this time, during Emperor Hadrian’s reign, the Romans constructed the Car Dyke along the western edge of the Fens. This ‘canal’ is an 85-mile ditch, thought to have provided a transport route for heavy goods and supplies between Cambridge and York. Although Car Dyke and waterways from the same early period were canals by the definition we saw earlier, some may have been only partly navigable at best. It is possible, if not likely, that their role in controlling natural water systems was at least as important as their use for transport. After all, the Romans were also ace road builders.

The oldest canal built by the Romans in England which is still in use today is the Foss Dyke. Built around 120 AD, this waterway connected the Trent with the thriving Roman metropolis of Lindum Colonia (Lincoln), and was fully navigable along its entire length. The Foss Dyke Canal isn’t huge, running for a little over 11 miles from Torksey Lock on the River Trent until, passing through Brayford Pool in Lincoln, it meets the River Witham.

But, with the Witham, the navigation continues under High Bridge (also known as the Glory Hole) on its way to Boston and The Wash, thus providing easy access to the North Sea. Not daft, those Romans.

SharpieType301 2017

Some later, post-Roman, canals exist in Britain, but it wasn’t until the second half of the 18th century that the great age of canal building took flight, coinciding with and driven by the burgeoning Industrial Revolution, as formerly agricultural societies became more industrialised and urban.

With the transition to new manufacturing processes, taking traditional hand-processes and mechanising them, coal was required to produce steam to power the new steam engines. This coal was needed in ever greater amounts. So, for these machines to work efficiently, they depended upon an effective transport system, carrying the commodities (like coal and raw materials) into the industrial centres, and hauling the finished goods out from the point of production to the ports.

By the late 1600s, attempts to dredge and widen navigable inland waterways had been made, but rivers and smaller natural waterways simply couldn’t provide the necessary links for the new industrial centres. Rivers are captive to the landscape they flow through, so don’t always pass by where they’re most needed, and their navigability can be affected by drought, flooding, and erosion.

The first canal in Industrial Age Britain to be built without following the course of an existing river or tributary, was the Bridgewater Canal, also known as ‘the Dukes Cut’. The Sankey Brook Navigation (which became known as the St Helens Canal), was built slightly earlier, but this had followed the valley of the Sankey Brook.

Permission for building roads and other public works has been granted (er, or not) by Acts of Parliament since mediaeval times. Parliament uses so-called Private Acts in order to authorise new canal routes (these are ‘private’ as they are ‘local’ or ‘personal’ acts, awarded to specific individuals or bodies, rather than changing the law as it applies to the general public).

The Private Bill presented to Parliament by Lord Francis Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater to request permission for his canal to be built had been enthusiastically supported by traders in Manchester and Salford as he had promised to greatly reduce the price of coal delivered to them. The Bill received Royal Assent, and the enabling Act for the ten-mile-long Bridgewater Canal was passed in 1759, with work starting in the same year.

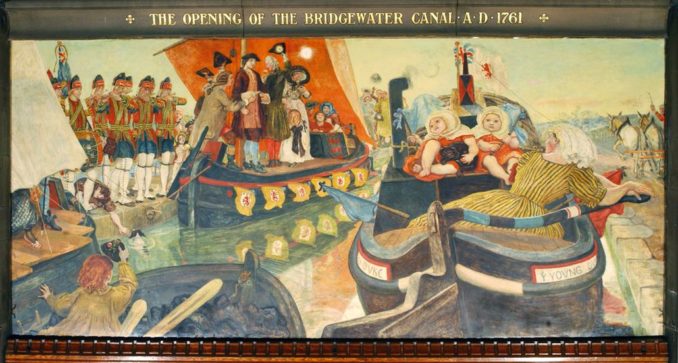

The Bridgewater Canal duly opened to much excitement on 17th July 1761. It was conceived and built by the Duke, to transport coal and other heavy commodities from his estates at Worsley, and other Lancashire mines, to Manchester. This city was the world’s first industrial city—its steam engines powering the textile industry.

Because of this incredible entrepreneurial undertaking, Egerton, 3rd Duke of Bridgewater, who was a mere twenty-five-years-old at the time, is fondly remembered as the ‘Father of Inland Navigation’. Quite an accomplishment for someone considered both awkward and lacking in intelligence as a child, and whose early education had been all but entirely neglected.

Image from Wikipedia, Public domain

This was no bargain-basement undertaking. The Duke alone financed the project, putting his money where his mouth was and borrowing some £25,000 to fund it, a massive sum for the time. Although built to cover a relatively short distance, the Bridgewater was quite a feat of engineering. Together with his land agent John Gilbert, a mining engineer, The Duke devised an ingenious and unique solution to both solve a drainage problem for his mines and provide a reliable water source for the canal. This was to construct an underground canal, in fact a series of tunnels running along the coal seams, which directly linked the mines at Worsley to the surface canal. This allowed coal to be transported to the surface without difficulty as it could be mined and carried underground by boat to the main canal.

Appointed to aid the Duke in his endeavours was another young man, a similar misfit in many ways, but one who the world would come to see as synonymous with canals: James Brindley.

Tony Hisgett, licensed under CC BY 2.0

At the time he was engaged, he was only just in his forties, and had never actually built a canal before. That said, his technical expertise was considerable. This was initially acquired when, as a seventeen-year-old lad, he apprenticed himself to a millwright. That said though, partial to building models as a child, he was said to have a natural bent for design and engineering. By the age of twenty-six he’d founded his own business in Leek as a wheelwright and before long had gone on to construct mills and steam engines. As practical a man as he was clever, Brindley was comfortable working with and repairing numerous different types of machinery, but throughout his life he demonstrated a considerable interest in managing flows of water.

An exceptionally skilled man, he had acquired a reputation as a creative and inventive problem solver. Indeed, he was celebrated for making water run uphill when he devised and installed a water-powered pumping system at Salford’s Wet Earth Colliery. So successful was Brindley’s solution in operation that the basic components were still in use some 170 years later.

Parrot of Doom, licensed as public domain

A misfit, as I mentioned, Brindley was a fascinating man. He had received no formal schooling and was not a literate man by any stretch. He was a self-taught engineer, and his innovative concepts were designed without the aid of written calculations or drawings. He left no records of his projects except for the workings themselves and a few hand-scribed notebooks, which have only recently been found and transcribed. In these, his words, typical of a man who had little conventional education, were written as he would have spoken, spelt phonetically.

One of his most important achievements, and perhaps his greatest legacy, was to develop and enhance ‘puddling’, a previously known but somewhat haphazard technique. His enhanced method was used to waterproof and maintain canals over permeable ground. The puddling process, which is still used to this day is, in effect, squeezing and compacting clay to a putty-like state where any air bubbles (and other impurities) are totally removed. The resulting ‘puddled’ clay gives a completely inorganic, watertight, strong clay base for any channels or ponds, thus it was, and is still, widely used for lining canals, reservoirs, and dams. Never bettered, it is even used in modern flood defence projects and for lining and capping landfill sites to prevent leaching and pollution.

It was Brindley who suggested altering the Duke’s proposed route for the Bridgewater Canal, following the natural contours of the land to render it a completely lock-free, gravity-flow canal. A further Bill was presented to Parliament in March 1760, and passed, giving approval to the change of route. Although a little circuitous, the new route would make connections to any future canals (which were already on the cards) considerably easier. Slightly longer, it remained cost-effective as significant sums were saved on lock-building.

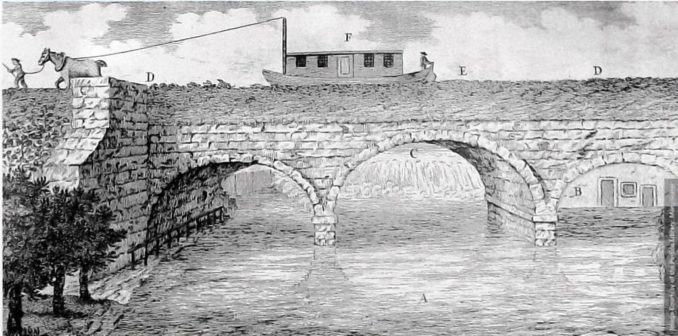

His planned route did, however, require an aqueduct, and the idea of carrying a canal across a river was considered a crazy notion—his plan drew scorn. Nevertheless, the stone-built Barton Aqueduct, the first navigable aqueduct to be built in England, was erected some 40 feet above the River Irwell to carry the canal across, and it remained in use for over 130 years. It immediately became quite an attraction, and visitors travelled from afar to watch barges on the aqueduct, travelling over boats on the river.

Irlam, Cadishead, Rixton with Glazebrook old photos, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

A magnificent achievement, the Bridgewater Canal became a template for all those that followed it, and ushered in a period of intense canal building, known as ‘Canal Mania’.

Despite the significant costs of building the canal, it was a great triumph for the Duke, who quickly made his money back. Indeed, so successful was this new transport route, that the price of coal in Manchester fell by half with the coming of the Bridgewater. This stimulated increased production at the Duke’s collieries, and the cheaper it became; the more coal was sold. Those traders in Manchester and Salford were vindicated in their support, and between sales of his coal and his new canal interests, the Duke became an incredibly wealthy man, possibly the richest nobleman in England at the time.

Just as well, as canal building wasn’t always plain sailing, and some of the costs accrued could be slightly indirect and, in part, political in nature. This can be seen from the Duke’s next plan, to extend his canal to the Mersey, linking with the Port of Liverpool, which met with substantial opposition.

Objections were raised by several parties. The Mersey and Irwell Navigation Company were furious, but their protests were overcome by the Duke buying a controlling interest in the company. In addition, landowner Sir Richard Brooke of Norton Priory wasn’t happy. He was worried that the uncouth boatmen might go a-poaching on his land, affecting his game and wildfowl. Brooke was adamant that he did not want the canal to pass through his property and successfully held up the process, until suitable compromises were reached. I can find no record of the price of these compromises, but rather wonder what that cost the Duke.

As for James Brindley, the Bridgwater was the start of something great indeed. As you’d imagine, given the success of the Bridgewater, more canal commissions came his way. Of these, by far his biggest project was the one he commenced next.

This was to be the country’s first long-distance canal, the Trent and Mersey Canal. An engineering achievement of much greater significance, this was to incorporate 76 locks, 160 aqueducts, 213 road bridges and 5 tunnels, including the infamous Harecastle Tunnel, a lengthy tunnel, more of which we shall see later.

When complete, this connected two major rivers and passed through industrial areas in the heartlands of Britain. It also neatly linked, as he had already anticipated, with the route he’d proposed for the Bridgewater, giving access to the Mersey.

All in all, Brindley was responsible for designing and building a network of British canals which run for almost 400 miles, including not only the Trent & Mersey Canal and the Bridgwater Canal, but the Staffordshire & Worcestershire Canal, Droitwich Canal, Coventry Canal, Birmingham Mainline Canal, and Oxford Canal.

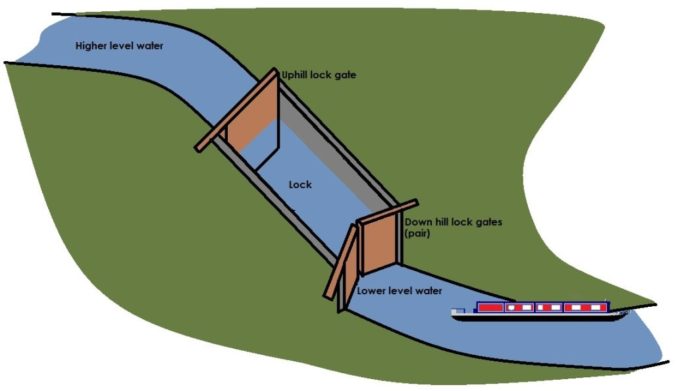

Interestingly, prior to the Trent and Mersey canal project being set in motion, Brindley’s completed canal work had not allowed for the waterway to traverse land which was not pretty much all at one level. He hadn’t included locks on the Bridgwater, those ever-present canal contraptions which are necessary to raise, and lower craft between stretches of water of different levels.

Undeterred by his lack of experience in this matter, he set to and experimented, building a series of prototype locks in the grounds of his own house, Turnhurst Hall. His efforts led him to develop his favoured design, one which still characterises locks across the Midlands canals today.

This has a hinged single upper gate and a pair of double-leaf lower gates. Upon closure the slightly oversized lower gates form a mitre, meeting with an angle pointing upstream. As the point faces the opposing downward flow of the stream, this design ensures the lock gates will remain securely closed against the water, as they can only be opened once the water level on each side of the gates has equalised. Ingenious indeed.

SharpieType301 2022

Work started on the Trent and Mersey Canal (otherwise known as the Grand Trunk Canal) in 1766. This was to be the first stage of what Brindley envisaged as ‘The Grand Cross’, a silvery waterway network of canal systems linking the four great navigable rivers of England: the Mersey, the Trent, the Severn, and the Thames, thus providing access between London and major ports at Bristol, Liverpool, and Hull.

In fact, there had been some earlier proposals for a ‘trunk’ canal. An early plan to open up the waterways across Britain by building a canal southward from the Mersey had been proposed in 1755. Sadly, no indication of the intended route exists, nor why its proponents didn’t press ahead with the idea. But five years later, in 1760, Granville Leveson-Gower, Marquis of Stafford and brother-in-law of the Duke of Bridgewater, drew up his own plan for what would become the Trent and Mersey Canal.

This was to run through the area in which this piece is written. But what, one might ask, was so important about the Potteries?

As so often, it’s a case of following the money. Soon after Lord Gower’s canal plan was announced, in 1761, young industrialist Josiah Wedgwood pledged his support. His initial interest was in providing his factories with access to the river Mersey and the Liverpool ports, not really connecting the rivers Trent and Mersey. But he used his influence to ensure that the proposed route should be to his advantage. Thus, the canal’s design linking the Trent (originally at Derwent Mouth, Derbyshire) to the Mersey, critically, ran through the heart of the Staffordshire Potteries, where his business was based.

The geological strata of North Staffordshire are uncommon, intermingling a plentiful variety of both clays and coals. These, plus ironstone and a range of useful minerals, had been extracted from the late 1200s for small-scale production of pottery at Burslem. By the mid-1400s, demand had already grown, and coal from the important Great Row seam at Apedale was being mined for use in kilns to fire ceramics. By the late 1700s, some of the great pottery manufacturers (such as Spode, Minton and Wolfe) had joined forces to open their own collieries to mine the valuable coal for the benefit of their industries.

Hence the reason behind this area’s escalating prominence was the local availability of materials required for a wealth of ceramic production: a number of local coarse clays and marls for bricks, tiles, and pottery, an abundance of the ‘long-flame’ coal required for high-temperature kilns, and also materials used in glazes—the salts (from nearby Cheshire) and lead (in the form of galena, lead sulphide, from neighbouring Derbyshire).

However, as production began to ramp up with the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, a snag was observed. Increased production of these precious, but fragile goods exposed great need for swift, reliable, and cost-effective transport.

The proposed canal system would enable yet greater quantities of coal, and other raw materials to be brought into The Potteries to create the world-renowned ceramics and allow increased production. In addition, better access to the prized high-purity Cornish china clay (kaolin, otherwise known as ‘white gold’), and other important commodities would both upgrade the quality of the fine china and porcelain manufactured.

It was a no-brainer. First-class transport, in the form of a canal system, was also essential for moving the precious, but bulky and fragile pottery out to other areas of the country, indeed the world, for sale. Josiah Wedgwood’s high-end ceramics, carried by packhorse over the rough, uneven roads of the 1700s, were easily damaged, no matter how well-packed. The potential wastage, both financially and in goods lost, was huge. Overland methods of transport were also slow and ineffective since large loads could not be carried.

An astute businessman, Wedgwood deemed his materials and goods much more likely to be shipped efficiently, and his products much less likely to be delivered in pieces, if they could be transported by water. These facts, alongside better access to raw materials in bulk, had kindled Wedgwood’s keen interest in canals.

This led to a meeting in March 1765 between Josiah Wedgwood, James Brindley, Erasmus Darwin, and Thomas Bentley, which is sometimes seen as a pivotal moment which helped shape the history of the Industrial Revolution. These prominent men came together in a back room in The Leopard Inn, at the Market Place in Burslem, a hostelry established by Ellen Wedgwood, a distant cousin of Josiah Wedgwood. They were there to discuss the creation of The Trent and Mersey Canal.

This historic inn still stands today—a well-known and well-loved pub, descriptions of it featured in several of Arnold Bennett’s Five Towns’ novels (though he renamed it ‘The Tiger’). Sadly, it now seems that The Leopard’s long history may have come to a depressing end. In January this year, police discovered a cannabis factory inside the pub. Just days afterwards, a suspected arson attack destroyed much of the building, including a series of murals (including one depicting the legendary 1765 meeting) painted by a local artist, which had been on view to all in the Arnold Bennett suite, at the back of the Leopard Hotel.

The plans developed at the famed meeting received royal assent in May 1766. However, once again, the canal plans faced opposition from various ‘interested parties’. The fact that the canal could bring coal in from Cheshire was perceived as a threat to coal merchants in Liverpool. The River Weaver Navigation’s owners were less than pleased as the route would almost parallel that of the river but, being straighter and shorter, could potentially take away a considerable amount of their existing business. Once again, political shenanigans ensued to overcome these problems.

So, it came to be that, later in 1766, the first section of the Trent and Mersey was dug at Middleport, an industrial district to the west of Burslem, so-called ‘mother town’ of Stoke-upon-Trent. The first sod was cut, with great ceremony, by Josiah Wedgwood himself. With the route now agreed and approved, Wedgwood developed a new, modern ‘factory village’, close to the canal route, which completely opened in 1769. He named his new site Etruria, to honour the Etruscans, a people famed for their great artistry.

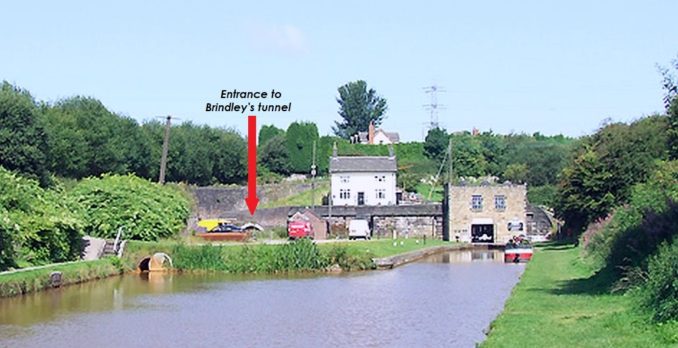

By 1777, the canal was nearing completion. The only remaining substantial obstacle was the hill at Kidsgrove, as goods from Wedgwood’s new pottery still had to be carried up and over the top to re-join the canal on the other side. Not ideal, although a tunnel, the infamous Harecastle Tunnel, which had been started in 1766, was being built between Kidsgrove and Tunstall. James Brindley was in his element here, but the work proved daunting, mostly because of the variable nature of the underlying rock, which caused a welter of engineering complications. This was a massive undertaking. In the end, at nearly 2 miles long, it took until 1777, some 11 years, to complete.

Roger Kidd, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Sadly, during this time Brindley was caught in heavy rain, whilst out and about surveying for a new branch of the Trent and Mersey Canal. He foolishly slept in his still wet clothing so woke with a chill and, although soon under the care of his friend, the physician Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles), he quickly became seriously ill. He died from complications arising from his diabetes, at his home at Turnhurst, within sight of the Harecastle Tunnel on 27 September 1772, before the tunnel’s completion, and before the canal system was finished. A dedicated man to the end, he died in harness, as even on his deathbed he was approached for advice on canal construction.

Brindley’s Harecastle Tunnel is 2880 yards in length, more than double the length of the Trent and Mersey’s Preston Brook Tunnel and was reputedly the longest man-made tunnel on Earth at the time. Indeed, it was described by a writer in 1767 as “the eighth wonder of the world …“. Nothing of this scale had ever been attempted before. At only 9 feet wide at its maximum, it had no towpath. The barge horses were walked over the top of Harecastle Hill along a path which is still called ‘Boathorse Road’. Meanwhile, the boats had to be ‘legged’ through the tunnel.

‘Legging it’ was a slow and physically arduous process, where the bargees, lying on their backs on a plank across the bows of the boat, ‘walked’ the laden barges through the tunnel, pushing with their feet against the tunnel walls and roof to move them. Dudley Canal Trust have produced a fascinating little video demonstrating the legging process:

Legging it! How to Leg a Narrowboat through a Canal Tunnel

With increasing amounts of barge traffic, the slow process of legging the laden barges through Harecastle Tunnel (it could take up to three hours for a boat to leg it through!) made it a significant bottleneck, limiting transport on the Trent and Mersey Canal.

Thus, in the early 19th century, a second, larger, slightly longer tunnel, complete with a towpath, was built by Thomas Telford. This runs parallel to Brindley’s original, which was eventually closed in 1914 after ongoing problems with subsidence. Even today, with diesel-powered boats, it takes around 30–40 minutes to pass through the Harecastle—it’s not for the fainthearted.

Finally, in May of 1777, five years after Brindley’s death, the entire course of the Trent and Mersey Canal was open for operation. It was proclaimed another triumph; a 93.5 mile stretch with more than 70 locks and no less than 5 tunnels along its length. It connected the Mersey and the major port of Liverpool via the Bridgwater canal, right through the heart of England to the Trent which, as it is navigable all the way to its mouth on the Humber Estuary, gave access to the Port of Hull.

The final cost for the construction of the Trent and Mersey Canal stood at £296,600, over £54,000,000 today. How much was paid out in additional costs and kickbacks to smooth its progress and overcome local objections at various points along its length can only be guessed at.

OpenStreetMap, licensed under Open Data Commons Open Database License (ODbL)

Areas along the entire route of the Trent and Mersey Canal benefitted. Many industries, not only the potteries, prospered with the coming of the canal, as transport expenditures dropped to a quarter of their previous costs. Coal mining is perhaps the most obvious, but the canal brought enhanced prosperity to Burton-on-Trent, as it allowed the town to develop yet further to become the ‘brewing capital’ of Britain (with around a quarter of UK beer brewed there, and considerable volumes brewed for export throughout the British Empire). The Cheshire salt industry for food and industry, with its mines and salt pans at Middlewich, Nantwich, Northwich and Leftwich (the Cheshire ‘wiches’), and Winsford prospered too. All this, before we even consider the industries connected by subsequent nearly 4,000 miles of linked canals, which criss-crossed Britain.

Perhaps it is too much of a stretch to attribute all of this to a single man, but without the genius and dedication of James Brindley, we wouldn’t have seen the canal systems develop. This modern method of transport ushered in the start of a new era, the Industrial Revolution, and drove the transformation of the British landscape and its people. Innovation and industrialisation led to Britain becoming the world’s leading commercial nation, to the rise of the British Empire, and even sowed the seeds of the abolitionist movement. Not bad for an unschooled Derbyshire lad, who spent most of his life in Staffordshire.

Between 1791 and 1795, around 44 Acts agreeing the construction of new canals were passed, largely financed by industrialists and investors hoping to make a profit on the waterways. This continued Brindley’s legacy, and the volume of goods these waterways carried increased dramatically, with the canal network expanding to almost 4000 miles of man-made waterways. This was the Golden Age of the canal network, and it was significant but, sadly, not terribly long lived.

Some of the new canals were built speculatively, rather than on the back of solid economic need, so some substantial losses were made instead of the anticipated profits. The ‘Father of Economics’ Adam Smith pointed out in 1776 that:

“Navigable cuts and canals are of great and general utility; while at the same time they frequently require a greater expense than suits the fortunes of private people.”

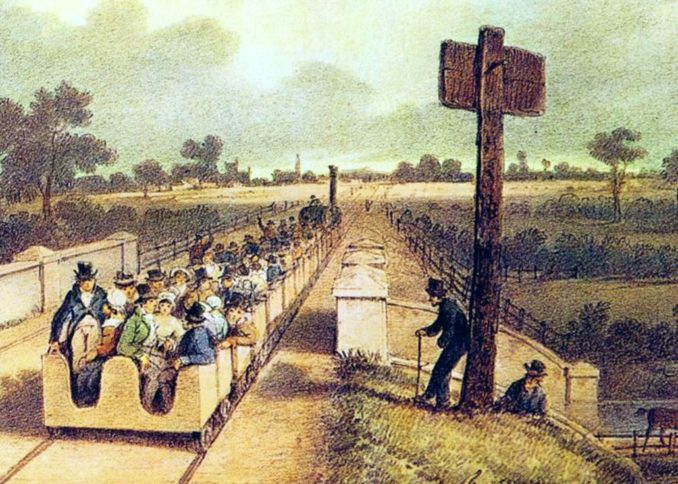

Inevitably, the minds of investors were focused on profits and cost effectiveness, and new transport methods were beginning to be established. The Liverpool to Manchester railway, opened in 1830, rang the death knell for the canal network, as it was proof positive that a cheaper and more efficient alternative to canals was now available.

From their initial construction onwards, canals were a more costly proposition than the new railways. They were subject to potential problems such as low water levels in summer or freezing in winter, whereas the railways were not. In comparison to the emergent rail network, canals were a slower mode of transport. Travel between Liverpool and Manchester took one and three-quarter hours by rail, yet a massive 20 hours by canal. Crucially, the canal barges capacity for transporting goods in bulk was secondary to railways, so business began to be lost.

A.B. Clayton, public domain

One final advantage, and one which ushered in a number of substantial social, political, and economic effects, was that the rail network introduced passenger travel. This was to change the complexion of Britain utterly and may be the subject of another article one day.

However, none of this can diminish James Brindley’s extraordinary legacy in any way, so perhaps I’ll leave it to his friend, Erasmus Darwin, to say a few words about him, with this tribute to Brindley in his poem ‘The Economy of Vegetation’:

“So with strong arm immortal Brindley leads

His long canals, and parts the velvet meads;

Winding in lucid lines, the watery mass

Mines the firm rock, or loads the deep morass,

With rising locks a thousand hills alarms,

Flings o’er a thousand streams in silver arms,

Feeds the long vale, the nodding woodland laves;

And Plenty, Arts and Commerce freight the waves.”

© SharpieType301 2022