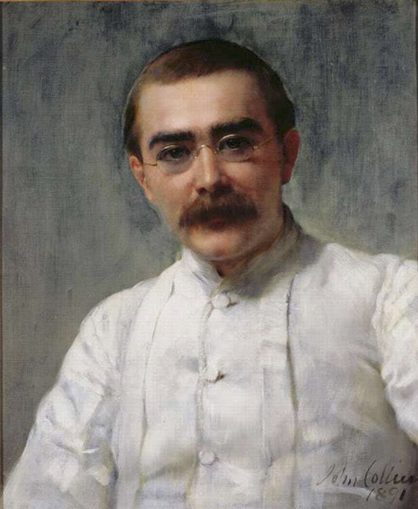

John Collier, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

‘When the Rudyards cease their Kipling, and the Haggards ride no more…’ was a favoured line in the era of post Imperial breast-beating, when this voluminous and best-selling writer, both in verse and prose was being ‘cancelled’ in the last Century as not only an Imperialist but a Jingoist, in those years when only Republicans or Communists were considered the right people to make Empires; although the procrustean term ‘Racist’ had, unfortunately, not then been invented, he was plainly (another mere ‘boo-word’) ‘right-wing, a xenophobe, …

Presumably these people, if they had actually read some of what he wrote, or had understood what they read, would, in any case, have dismissed him as ‘Popular’, that ultimate put-down. Decades before, that amazingly perceptive writer G. K. Chesterton, had delineated the difference between ‘Writer’ and ‘Journalist’, as lying in the word ‘successful’. Both Elgar and Sibelius had detractors who asked why these undeniably great Composers should waste their time – indeed, sully their hands – with [mere]‘popular music’: they did not stop to ask why it should be deemed the task only of lesser talents to write for ‘the masses’ nor whether the ‘Great’ should not be allowed ever and anon to frolic at perhaps sub-parnassian heights. No, Art must be grim, incomprehensible, lengthy and unpleasant to the ear and /or eye…

I was in my last Year of reading English in 1964, when a frisson of alarm passed through the English Faculty: Mr. Ricks (subsequently Professor Ricks) had proposed a course of lectures on Rudyard Kipling! The Oxford English School then terminated with ‘Authors who had made their reputation by 1899’ (I speak from memory, it could have been 1901…)

Jingoist

‘We’ve got the men, we’ve got the guns, we’ve got the money too!

Above all, perhaps even above being a story-teller, Kipling was a Reporter: he remembered accurately, and wrote down, what people said; he did not edit, smooth the edges, press into a mould – except that politeness, custom, reverence required that he, like many of those for whom he spoke, put an innocuous word in place of a blasphemous use of The Saviour’s name (cf. American ‘Gee’ or ‘Jimminy Cricket’ or ‘Christopher Columbus’). The fact that he so memorably records what ‘the people’ were saying before the Boer War, does not then mean that Kipling assented to, or endorsed those sentiments. In ‘Macbeth’ Shakespeare wrote about a regicide who becomes a mass-murderer: Shakespeare, by that marvellous faculty Keats dubbed ‘Negative Capability’ ‘gets into the mind and under the skin’ of such a man; Shakespeare is no regicide.

Racist/White-Supremacist

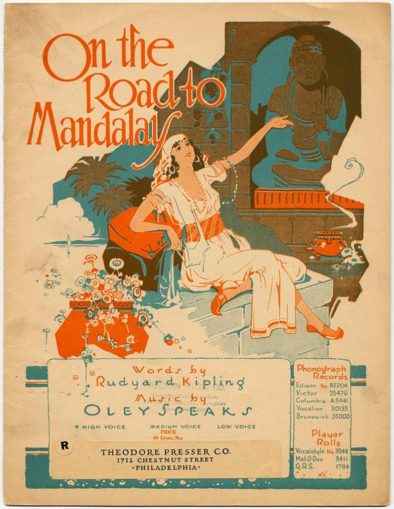

Unknown authorUnknown author, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The road to Mandalay delicately records a ‘British Soldier’s’ encounter with a native girl somewhere in Burma…’ I kissed her where she stood’ [‘Plucky lot she cared for idols when I kissed ‘er where she stud!’] where she’d been offering homage to Buddha. No doubt, ‘kissed’ is an euphemism. Well into the Twentieth Century – certainly until Andrew Marr had publicly advocated ‘vigorous miscegenation’- there existed a popular notion that cross-breeding was wrong- indeed, in living memory, there were places (like North Devon!) where courting – let alone marrying – ‘out’ (i.e. from another part even of the same village) was regarded as ignominious.

Rockrangoon, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

‘He’ “knows” this ‘Burma girl’ ‘thinks of me’: has he left her a reminder of when, gun aslung, perhaps, he’d ‘kissed ‘er where she stud’? She’d been smoking ‘a whackin’ white Cheroot’ and ‘wastin’ Christian kisses on an ‘eathen Idol’s foot’ ‘wot they calls the great Gawd Bud’. Now Kipling knows – and reckons most of his educated audience knows -that there is no God in Buddhism, and that kisses cannot really be described as ‘Christian’, but so exactly – or pretty much exactly – not merely might or would, but did an ‘English Soldier’ of the era think.

So far, so bad: non-consensual sex, enforced at rifle-point?

But then this very Cockney soldier goes on:

‘When the mist was on the rice-fields an’ the sun was droppin’ slow,

She’d git ‘er little banjo an’ she’d sing “~Kulla-lo-lo!~”

With ‘er arm upon my shoulder an’ ‘er cheek agin’ my cheek

We useter watch the steamers an’ the ~hathis~ pilin’ teak.

Elephints a-pilin’ teak

In the sludgy, squdgy creek,

Where the silence ‘ung that ‘eavy you was ‘arf afraid to speak!

So, the ‘British Soldier’ has found and learned something his ‘Christian’ upbringing has not taught him – something, moreover he has had to learn from ‘an ‘eathen’: tenderness, and contemplation.

‘and it’s there that I would be, by the old Moulmein Pagoda looking lazy at the sea.’ Is it straining things, for me to see in that one word ‘lazy’ an implicit evocation of post-coital bliss, what Shelley referred to as ‘love’s sweet-sad satiety’? Kipling was himself struck by the beauty of the Burmese women, writing, ‘I love the Burman with the blind favouritism born of first impression. When I die I will be a Burman … and I will always walk about with a pretty almond-coloured girl who shall laugh and jest too, as a young maiden ought. She shall not pull a sari over her head when a man looks at her and glare suggestively from behind it, nor shall she tramp behind me when I walk: for these are the customs of India. She shall look all the world between the eyes, in honesty and good fellowship, and I will teach her not to defile her pretty mouth with chopped tobacco in a cabbage leaf*, but to inhale good cigarettes of Egypt’s best brand.’ [* that ‘whackin’ white cheroot’?]. And notice here, the English distinction, long lost on Americans and now among many Englishmen, between ‘shall’, and ‘will’ – it is there in the old Nursery Rhyme ‘Goldilocks, Goldilocks, wilt thou be mine, Thou shalt not wash dishes, nor yet feed the swine..’: I, the singer, will ensure that dish-washing, let alone pig-feeding, is not to be thy lot. In Kipling’s dream/imagination, he will ensure that – talk about male privilege! – ‘the Burman’ will be enabled to be as straightforward as to ‘look the world between the eyes, in honesty and good fellowship…’. Then there’s the astonishingly radical- nay, revolutionary – ‘who shall laugh and jest too, as a young maiden ought.’ Young maidens laughing and jesting! Whatever next! What need is there for Feminism, what need for anti-racialism, what need for Puritanism, when there’s Kipling?

And what an ear: ‘In the sludgy, squdgy creek’: apart from the alliteration and near-rhymes of the two words, I think Kipling has created a new word in ‘squdgy’ (it’s not ‘squidgy’ – ‘Gunga Din’s nose is squidgy) so that there’s Onomatopoeia: ‘sludgy’ suggesting (to me) the sound of an Elephant’s foot treading down into the mud, ‘squdgy’ the almost-squeaky sound as he withdraws his foot.

No wonder he won the Nobel Prize, in the days when you had to deserve it, not merely by being ‘flavour of the month’ among the Globalists. And that, not merely for his astonishing industry, but for the sheer quality of his writing: the way he enters into the lives of his characters, magically enabling us to enter into them too:

‘I keep six honest serving-men

(They taught me all I knew);

Their names are What and Why and When

And How and Where and Who.’

That, I suppose, is the key to it: he asked questions, took note of the answers, and by a miraculous process of mental-digestion, assimilated this raw-material and made of it stories, tales, ballads, and so on – spinning straw into gold.

I have not been able to verify the reference (no doubt someone here will be able to) – was it C.S. Lewis? – who noted the paradox that, for an essentially homeless man, Kipling had an acute sense of ‘home’. So he lived for a while in Rottingdean, then moved to Burwash, where the house he and his wife fell in love with – Bateman’s – now run by the odiously ‘woke’ National Trust! – became their home, and where his desk can be seen, with all the accoutrements necessary for the laborious business of actually putting pen to paper (N.T. ‘curated’?).

Of course, he became a wealthy man, and so belonged to that stratum of society to which another Englishman of the same era belonged, Edward Elgar: neither was of the ‘pull up the ladder, Jack…’ type.

‘But, what about the “lesser breeds without the Law”, eh?

Our England is a garden that is full of stately views,

Of borders, beds and shrubberies and lawns and avenues,

With statues on the terraces and peacocks strutting by;

But the Glory of the Garden lies in more than meets the eye.

For where the old thick laurels grow, along the thin red wall,

You’ll find the tool- and potting-sheds which are the heart of all

The cold-frames and the hot-houses, the dung-pits and the tanks,

The rollers, carts, and drain-pipes, with the barrows and the planks.

And there you’ll see the gardeners, the men and ‘prentice boys

Told off to do as they are bid and do it without noise ;

For, except when seeds are planted and we shout to scare the birds,

The Glory of the Garden it abideth not in words.

And some can pot begonias and some can bud a rose,

And some are hardly fit to trust with anything that grows ;

But they can roll and trim the lawns and sift the sand and loam,

For the Glory of the Garden occupieth all who come.

Our England is a garden, and such gardens are not made

By singing, “Oh, how beautiful,” and sitting in the shade

While better men than we go out and start their working lives

At grubbing weeds from gravel-paths with broken dinner-knives.

There’s not a pair of legs so thin, there’s not a head so thick,

There’s not a hand so weak and white, nor yet a heart so sick

But it can find some needful job that’s crying to be done,

For the Glory of the Garden glorifieth every one.

Then seek your job with thankfulness and work till further orders,

If it’s only netting strawberries or killing slugs on borders;

And when your back stops aching and your hands begin to harden,

You will find yourself a partner In the Glory of the Garden.

Oh, Adam was a gardener, and God who made him sees

That half a proper gardener’s work is done upon his knees,

So when your work is finished, you can wash your hands and pray

For the Glory of the Garden that it may not pass away!

And the Glory of the Garden it shall never pass away!

I have italicised ‘while better men than we’: there is an almost identical phrase in another of his poems:

You may talk o’ gin and beer

When you’re quartered safe out ’ere,

An’ you’re sent to penny-fights an’ Aldershot it;

But when it comes to slaughter

You will do your work on water,

An’ you’ll lick the bloomin’ boots of ’im that’s got it.

Now in Injia’s sunny clime,

Where I used to spend my time

A-servin’ of ’Er Majesty the Queen,

Of all them blackfaced crew

The finest man I knew

Was our regimental bhisti, Gunga Din,

He was ‘Din! Din! Din!

‘You limpin’ lump o’ brick-dust, Gunga Din!

‘Hi! Slippy hitherao

‘Water, get it! Panee lao,

‘You squidgy-nosed old idol, Gunga Din.’

The uniform ’e wore

Was nothin’ much before,

An’ rather less than ’arf o’ that be’ind,

For a piece o’ twisty rag

An’ a goatskin water-bag

Was all the field-equipment ’e could find.

When the sweatin’ troop-train lay

In a sidin’ through the day,

Where the ’eat would make your bloomin’ eyebrows crawl,

We shouted ‘Harry By!’

Till our throats were bricky-dry,

Then we wopped ’im ’cause ’e couldn’t serve us all.

It was ‘Din! Din! Din!

‘You ’eathen, where the mischief ’ave you been?

‘You put some juldee in it

‘Or I’ll marrow you this minute

‘If you don’t fill up my helmet, Gunga Din!’

’E would dot an’ carry one

Till the longest day was done;

An’ ’e didn’t seem to know the use o’ fear.

If we charged or broke or cut,

You could bet your bloomin’ nut,

’E’d be waitin’ fifty paces right flank rear.

With ’is mussick on ’is back,

’E would skip with our attack,

An’ watch us till the bugles made ‘Retire,’

An’ for all ’is dirty ’ide

’E was white, clear white, inside

When ’e went to tend the wounded under fire!

It was ‘Din! Din! Din!’

With the bullets kickin’ dust-spots on the green.

When the cartridges ran out,

You could hear the front-ranks shout,

‘Hi! ammunition-mules an’ Gunga Din!’

I shan’t forgit the night

When I dropped be’ind the fight

With a bullet where my belt-plate should ’a’ been.

I was chokin’ mad with thirst,

An’ the man that spied me first

Was our good old grinnin’, gruntin’ Gunga Din.

’E lifted up my ’ead,

An’ he plugged me where I bled,

An’ ’e guv me ’arf-a-pint o’ water green.

It was crawlin’ and it stunk,

But of all the drinks I’ve drunk,

I’m gratefullest to one from Gunga Din.

It was ‘Din! Din! Din!

‘’Ere’s a beggar with a bullet through ’is spleen;

‘’E’s chawin’ up the ground,

‘An’ ’e’s kickin’ all around:

‘For Gawd’s sake git the water, Gunga Din!’

’E carried me away

To where a dooli lay,

An’ a bullet come an’ drilled the beggar clean.

’E put me safe inside,

An’ just before ’e died,

‘I ’ope you liked your drink,’ sez Gunga Din.

So I’ll meet ’im later on

At the place where ’e is gone—

Where it’s always double drill and no canteen.

’E’ll be squattin’ on the coals

Givin’ drink to poor damned souls,

An’ I’ll get a swig in hell from Gunga Din!

Yes, Din! Din! Din!

You Lazarushian-leather Gunga Din!

Though I’ve belted you and flayed you,

By the livin’ Gawd that made you,

You’re a better man than I am, Gunga Din!

Again, I’ve italicised those words, which date from 1890, Kipling was to utter the similar sentiment in that later poem, ‘The Glory of the Garden’ in 1911. And his feeling for the underdog, is also to the fore here:

I went into a public-‘ouse to get a pint o’ beer,

The publican ‘e up an’ sez, “We serve no red-coats here.”

The girls be’ind the bar they laughed an’ giggled fit to die,

I outs into the street again an’ to myself sez I:

O it’s Tommy this, an’ Tommy that, an’ “Tommy, go away”;

But it’s “Thank you, Mister Atkins”, when the band begins to play,

The band begins to play, my boys, the band begins to play,

O it’s “Thank you, Mister Atkins”, when the band begins to play.

I went into a theatre as sober as could be,

They gave a drunk civilian room, but ‘adn’t none for me;

They sent me to the gallery or round the music-‘alls,

But when it comes to fightin’, Lord! they’ll shove me in the stalls!

For it’s Tommy this, an’ Tommy that, an’ “Tommy, wait outside”;

But it’s “Special train for Atkins” when the trooper’s on the tide,

The troopship’s on the tide, my boys, the troopship’s on the tide,

O it’s “Special train for Atkins” when the trooper’s on the tide.

Yes, makin’ mock o’ uniforms that guard you while you sleep

Is cheaper than them uniforms, an’ they’re starvation cheap;

An’ hustlin’ drunken soldiers when they’re goin’ large a bit

Is five times better business than paradin’ in full kit.

Then it’s Tommy this, an’ Tommy that, an’ “Tommy, ‘ow’s yer soul?”

But it’s “Thin red line of ‘eroes” when the drums begin to roll,

The drums begin to roll, my boys, the drums begin to roll,

O it’s “Thin red line of ‘eroes” when the drums begin to roll.

We aren’t no thin red ‘eroes, nor we aren’t no blackguards too,

But single men in barricks, most remarkable like you;

An’ if sometimes our conduck isn’t all your fancy paints,

Why, single men in barricks don’t grow into plaster saints;

While it’s Tommy this, an’ Tommy that, an’ “Tommy, fall be’ind”,

But it’s “Please to walk in front, sir”, when there’s trouble in the wind,

There’s trouble in the wind, my boys, there’s trouble in the wind,

O it’s “Please to walk in front, sir”, when there’s trouble in the wind.

You talk o’ better food for us, an’ schools, an’ fires, an’ all:

We’ll wait for extry rations if you treat us rational.

Don’t mess about the cook-room slops, but prove it to our face

The Widow’s Uniform is not the soldier-man’s disgrace.

For it’s Tommy this, an’ Tommy that, an’ “Chuck him out, the brute!”

But it’s “Saviour of ‘is country” when the guns begin to shoot;

An’ it’s Tommy this, an’ Tommy that, an’ anything you please;

An’ Tommy ain’t a bloomin’ fool — you bet that Tommy sees!

We’re told that, when reciting his own poems, Kipling did not use the printed circumlocutions, giving rather more savagery to ‘Tommy’s’ last line.

‘Gunga Din’ invokes Hell – as does the marvellous poem ‘Tomlinson’ – which was the final poem in one of the 20th Century editions of Palgrave’s ‘Golden Treasury’ – which also sketches, perhaps, a glimpse of Purgatory: can ‘The Glory of the Garden’ represent this amazing writer’s ‘In Paradisum’?

George Orwell writes critically of Kipling, censuring the ‘mockney’ he makes his common soldiers speak in, but noting his genuine concern for their welfare: “…it remains true that he has far more interest in the common soldier, far more anxiety that he shall get a fair deal, than most of the ‘liberals’ of his day or our own. He sees that the soldier is neglected, meanly underpaid and hypocritically despised by the people whose incomes he safeguards. ‘I came to realize’, he says in his posthumous memoirs, ‘the bare horrors of the private’s life, and the unnecessary torments he endured’. He is accused of glorifying war, and perhaps he does so, but not in the usual manner, by pretending that war is a sort of football match. Like most people capable of writing battle poetry, Kipling had never been in battle, but his vision of war is realistic. He knows that bullets hurt, that under fire everyone is terrified, that the ordinary soldier never knows what the war is about or what is happening except in his own corner of the battlefield, and that British troops, like other troops, frequently run away:

I ‘eard the knives be’ind me, but I dursn’t face my man,

Nor I don’t know where I went to, ’cause I didn’t stop to see,

Till I ‘eard a beggar squealin’ out for quarter as ‘e ran,

An’ I thought I knew the voice an’ — it was me!…”

Orwell takes issue with T.S. Eliot: “…It was a pity that Mr. Eliot should be so much on the defensive in the long essay with which he prefaces this selection of Kipling’s poetry, but it was not to be avoided, because before one can even speak about Kipling one has to clear away a legend that has been created by two sets of people who have not read his works. Kipling is in the peculiar position of having been a byword for fifty years. During five literary generations every enlightened person has despised him, and at the end of that time nine-tenths of those enlightened persons are forgotten and Kipling is in some sense still there. Mr. Eliot never satisfactorily explains this fact, because in answering the shallow and familiar charge that Kipling is a ‘Fascist’, he falls into the opposite error of defending him where he is not defensible.” As to ‘those ‘lesser breeds…’, Orwell skewers it thus: And yet the ‘Fascist’ charge has to be answered, because the first clue to any understanding of Kipling, morally or politically, is the fact that he was not a Fascist. He was further from being one than the most humane or the most ‘progressive’ person is able to be nowadays. An interesting instance of the way in which quotations are parroted to and fro without any attempt to look up their context or discover their meaning is the line from ‘Recessional’, ‘Lesser breeds without the Law’. This line is always good for a snigger in pansy-left circles. It is assumed as a matter of course that the ‘lesser breeds’ are ‘natives’, and a mental picture is called up of some pukka sahib in a pith helmet kicking a coolie. In its context the sense of the line is almost the exact opposite of this. The phrase ‘lesser breeds’ refers almost certainly to the Germans, and especially the pan-German writers, who are ‘without the Law’ in the sense of being lawless, not in the sense of being powerless. The whole poem, conventionally thought of as an orgy of boasting, is a denunciation of power politics, British as well as German. Two stanzas are worth quoting (I am quoting this as politics, not as poetry):

If, drunk with sight of power, we loose

Wild tongues that have not Thee in awe,

Such boastings as the Gentiles use,

Or lesser breeds without the Law —

Lord God of hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget — lest we forget!

For heathen heart that puts her trust

In reeking tube and iron shard,

All valiant dust that builds on dust,

And guarding, calls not Thee to guard,

For frantic boast and foolish word —

Thy mercy on Thy People, Lord!

These two eminent writers feel obliged to keep both him and his poetry at arm’s length – Orwell finding the poetry ‘almost a guilty pleasure’, Eliot adjudging Kipling ‘… a writer impossible to understand and quite impossible to belittle.’ Both Eliot (Harvard; the Sorbonne) and ‘Orwell’ (Eton) evince, to me, a faint whiff of that snobbery – intellectual snobbery, if you will – that boils down to ‘How dare he write so well, without having had the very expensive education I had.’: the resentment of the ancien regime for the arrivé – and not a million miles from the destructive rage of a Crosland (Highgate School and Oxford – with Shirley Williams abetting him – St. Paul’s Oxford):”If it’s the last thing I do, I’m going to destroy every fucking grammar school in England. And Wales and Northern Ireland.”.

I mentioned Elgar earlier, the parallel here being that he was self-taught (not even United Services College!) and endured the sneering of his more academic contemporaries, such as Stanford, Dent, and so the Cambridge Music school and The Royal College of Music; Elgar – a very generous encourager of younger composers – also was subject to the camp (Orwell would have said ‘pansy’) ostentatious walking out of a young Benjamin Britten from an Elgar-conducted Elgar Concert, hissing ‘Nobilmente: sempre Nobilmente!’

Eliot wrote that Kipling had‘… an immense gift for using words, an amazing curiosity… the mask of the entertainer and beyond that a queer gift of second sight…’ I wonder whether the prophetic words of ‘Recessional’ were in his mind:

God of our fathers, known of old,

Lord of our far-flung battle-line,

Beneath whose awful Hand we hold

Dominion over palm and pine—

Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget!

The tumult and the shouting dies;

The Captains and the Kings depart:

Still stands Thine ancient sacrifice,

An humble and a contrite heart.

Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget!

Far-called, our navies melt away;

On dune and headland sinks the fire:

Lo, all our pomp of yesterday

Is one with Nineveh and Tyre!

Judge of the Nations, spare us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget!

If, drunk with sight of power, we loose

Wild tongues that have not Thee in awe,

Such boastings as the Gentiles use,

Or lesser breeds without the Law—

Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget!

For heathen heart that puts her trust

In reeking tube and iron shard,

All valiant dust that builds on dust,

And guarding, calls not Thee to guard,

For frantic boast and foolish word—

Thy mercy on Thy People, Lord!

– which sounds as if it might have been written some time during The Great War, but was actually written for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. In 1897, ‘Kaiser Bill’ appointed Admiral Tirpitz to be Secretary of State for the Imperial Navy, and the arms-race with The Royal Navy began: does Eliot see evidence for ‘second sight’ here in this melancholy warning poem?

These two critics seem determined to fault him – Orwell for being ‘vulgar’, ‘popular’, and writing platitudes (i.e., down to earth and truthful); Eliot, for being too lucid (no ‘underneath’) and too ‘hard and obscure’. For my own part, I stubbornly enjoy Kipling’s poetry.

© Jethro 2022