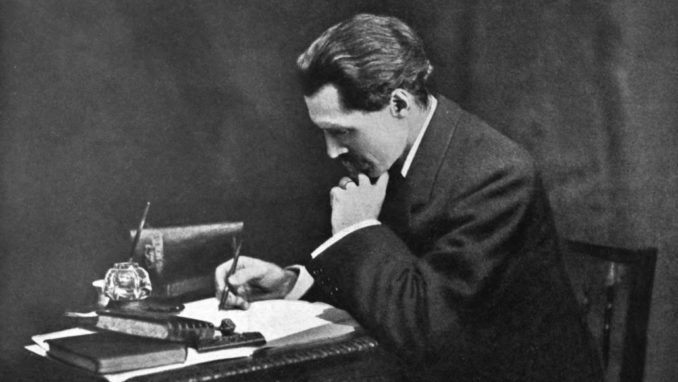

Elliott & Fry, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Russell Kirk the philosopher, compared George Gissing’s The Nether World to a literal Hell on earth. It was “the culmination of our social revolutions” which would make life more torturous. For New Grub Street, Kirk’s position still applies. This is a hell without salvation or the need for demons and divine punishment. The monsters of this novels are human and not altogether unsympathetic in their reasoning. The poor are of their own choosing. They were not born into this position, nor do they relish it as a way of ‘seeing the world’ anew. For them, poverty is an accepted fact of the role they feel obliged to take as artists. Their personalities being “wholly unfitted for the rough and tumble of the world’s labour-market.” If they would simply get along in life and wereEttrick Shepard willing to drop the act, they would not have so many problems. Gissing’s narrator even wonders when you have witnessed so much effort for so little gain how you truly feel. These men may:

“… merely provoke you. They seem to you inert, flabby, weakly envious foolishly obstinate, impiously mutinous, and many other things. You are made angry contemptuous by their failure to get on; why don’t they bestir themselves, push and bustle, welcome kicks so long as halfpence follow, make place in the world’s eye…”

Nevertheless, these men are also “richly endowed with the kindly and the imaginative virtues” and “it was in their nature and merit to be passive.” To hate them for not being able to make money or inability to explain their worth to the market is unfair because they never seek to make money. They have a higher principle. It may be phoney, or it may be naïve, but it is principles which gets us places. If everyone thought only of getting on in life, then extraordinarily little innovation would come about. We need those who self-sacrifice for their beliefs and desires to know our own limits. They set the rules which we, or our children, eventually follow or discard.

These characters, the writer’s block-stricken Edwin Reardon and the realist Harold Biffen, may excite the most sympathy, ugly pity, or contempt depending on your preference. For myself, Biffen, a man who knows his book will be failure and that men like him are condemned to “endure in solitude” elicited the most understanding. Reardon, who is married with child, could not bring as much sympathy, but his wife does not help in the situation. However, it is also John Yule, the invalid businessman who scorns all forms of writing, who in brings about as much understanding as Biffen. A man who has to witness his body’s decline and his greater family struggle would make any man scorn the writer’s life. He and Biffen work as doubles of one another because it in theirettr distinct worldviews they have genuinely responded to life. They do not conform and simply get on and in their own ways, have made something of the world. This does not include a happy life, but little does. I would enjoy neither as friends but reading about them leaves me in no doubt who I most align with.

It is Jasper Milvain who leaves me so empty. He is aware of his market, knows who the right editor is to work with, and caters carefully to his audience, the public and the private. It is fascinating what I would describe as healthy to a businessman, I find insufferable in Jasper. Witty and charming but lacking in all principle, he is the banality of evil. Not truly wicked, for he harms nobody conventionally, but an apathetic cruelty which never looks beyond his own gain. Whenever I heard him speak, I was certain his words were phoney. He writes a eulogy on the literary works of a recently departed acquaintance and you can smell why he writes his fawning praise, and it not for the dead. It is not a fault of Gissing for the reader to easily pinpoint Jasper before he acts, but the novel’s strength. Jasper is too much like myself for me not to notice what the right word can bring out when needed. He is not a grotesque villain of a Dickens, but a rationalised, humane malice which would never kill, but would never care all that much if someone did die. If anyone has read Michael Tolkin’s The Player or watched Robert Altman’s superb adaptation, then Griffin Mill is the modern Jasper. Educated, intelligent, and creative, yet lacking the moral core to hold it all together. It is as Brideshead Revisited’s Julia says her of husband:

“Rex has never been unkind to me intentionally. It’s just that he isn’t a real person at all; he’s just a few faculties of a man highly developed; the rest simply isn’t there.”

It is striking how little changed in the writing business. One idealises the past and assumes the aesthetic writer was supreme, but the more you know, the less romance it actually contains. The real artist exists and will remain in some capacity, and the great writings endure whilst the rest are forgotten. Some writers will make a living, most will not. It is the present which seems so ugly because we are incumbered by bad writing which is as forgotten as it quickly as it is read. It is frivolous entertainment. It was no different in the past:

“Let me explain my principle. I would have the paper address itself to the quarter-educated; that is to say, the great new generation that is being turned out by the Board schools, the young men and women who can just read, but are incapable of sustained attention. People of this kind want something to occupy them in trains and on ‘buses and trams. As a rule they care for no newspapers except the Sunday ones; what they want is the lightest and frothiest of chit-chatty information- bits of stories, bits of description, bits of scandal, bits of jokes, bits of statistics, bits of foolery. Am I not right? Everything must be very short, two inches at the utmost; their attention can’t sustain itself beyond two inches. Even chat is too solid for them: they want chit-chat.”

‘Chit-chat,’ for better or worse, is part of my own daily life. Needless apps, quick reads, endless scrolling, used to infest my daily life. My magazine was my smartphone and the websites I visit on it. Small nuggets of information were found in Tweets or search engines. Instead of publishing in a week, we publish automatically, and everybody is now a writer. Luddites can rightly point to the ills of the internet, but there is a grander point in New Grub Street about our priorities that go deeper than the technology enabling us. No matter how well-educated, a mob is a still mob, as TS Eliot rightly noted, and there must be a change in the education’s genuine purpose than from the bare minimum umbrella service we currently have. The frivolous literature of New Grub Street or found today is not harmless or outside of itself. It does have a power, more so than any classic ever would. Of course, those in the novel who peddle chit-chat are those who succeed and those who do not are the Reardons and Biffiens of the world.

This is a work ideal for the conservative who sees what he loves in perpetual decline. Immortality proven bung, justice turns to fiction, and the individual is helpless to stop any of it. Man is forever a beast of prey to one another. Society has an ugly omnipotence in this mindset. The social revolution of New Grub Street, one of writing and mass schooling, is like a new plague to endure before you pass into oblivion. There is no right answers and the solutions shouted from a pulpit would make only matters worse. Gissing is a writer who seems forever alone with himself, and his characters reflects this. They choose their situations and yet are fated to end up in there. It is a greater hell in a hellish landscape, but better my own nightmare than a nightmare pressed onto me by others.

© Ettrick Shepard 2022