Another chapter from “Special Assignment” by my uncle John Alldridge

(published in 1960 and now long out of print)

During the course of World War II the Press War Correspondent found himself in competition with a new kind of correspondent: a radio man who used a microphone and recording car and had an audience of millions anxiously waiting for him every night.

It was D-Day and the invasion of Europe that brought the radio correspondent into his own. Before then there was a school of thought that considered it not quite cricket to listen in to men in battle. When during the Battle of Britain in 1940 Charles Gardner gave a thrilling eye-witness account of a dogfight over Dover the B.B.C. was inundated with protests from people who objected that an incident in which men were losing their lives should not be treated like a horse race or a football match.

But by 1943 public opinion had changed completely. At the Trades Union Congress that year Sir Walter Citrine reinforced an appeal for increased production by referring to Wynford Vaughan-Thomas’s memorable commentary actually made in a Lancaster bomber flying over Berlin.

By then it seemed perfectly natural that civilians should hear, direct, the sounds of battle and the excitement experienced by the men who were actually ‘there’.

But radio war reporting was something quite new. It offered a two-way service. If the civilians by their firesides were hearing what was happening in the front line the men in the front line were hearing about it, too.

A newspaper correspondent could ‘colour up’ his dispatches and get away with it. A radio reporter dare not take the risk. No army thrives on being misrepresented: so woe betide the radio correspondent who failed to hold the confidence and goodwill of the fighting man by ‘shooting a line’!

There was also the new element of speed. A newspaper correspondent could sometimes afford to be a day or two late with his news. A radio man had to be right up-to-the-minute. It was no good reporting on the Six O’clock News that the battle was going well – as it may have been at ten o’clock in the morning – if by four in the afternoon the Army was already fighting a stubborn retreat.

This meant that radio had to introduce a new kind of reporter and new methods of recording and transmitting the news.

The B.B.C. already had many fine correspondents in the field. They had taught the civilians at home to move with the microphone along the dive-bombed roads of Greece, over the mountains of Abyssinia to Keren, to go wherever the fighting was, to listen and to ‘see’. But there were not enough of them to cope with the Second Front, while still covering other fronts. So it was the urgent job of the B.B.C.’s War Reporting Unit to select new recruits, train them and equip them with everything from transmitters to typewriter ribbons.

‘The recruits came from the various departments concerned in war reporting, and in the following months they went through an intensive course of special training,’ says the official history of the B.B.C. at war.

‘To begin with, a physical-training instructor tuned up what he called his “B.B.C. Commandos” for life in front-line conditions, and they were instructed in gunnery, signals, reconnaissance, aeroplane and tank recognition, and map-reading. They went on assault courses and battle courses, they crossed rivers on ropes and ducked under live ammunition. They learnt how to live rough and how to cook in the field. Some were attached to Regular Army units and shared every exercise with the unit. They ran cross-country against men maybe fifteen years younger and then finished the course. They often finished last, but they finished – and the Army didn’t like them any less for that.

‘On one occasion a dispatch rider was sent out to collect a lone B.B.C. correspondent who was still well down the course after the Regular Army men had long since finished. “Colonel’s orders,” said the dispatch rider. “The mess is waiting for dinner.” However the correspondent refused the lift and insisted on finishing the course. The colonel’s comment on this piece of insubordination deserves to be recorded. “Thank goodness you refused,” he said. “I bet a pound that you’d more guts than to give up before the finish.”’

Meanwhile the B.B.C.’s technicians and electronics experts were set the task of evolving some kind of lightweight recording gear which the radio reporter could carry with him.

This, of course, was before the days of the tape recorder. Until the end of the campaign in Africa all recordings in the field were on disc; and had to be made on heavyweight equipment weighing about 500 pounds, and mounted inside a truck. With such cumbersome gear it was virtually impossible to record on the spot.

That problem was solved by some wizard among the B.B.C. engineers who invented a portable midget recorder. This one-man portable recording unit looked for all the world like a portable gramophone. It weighed only 40 lb and carried twelve double-sided records – enough for a full hour’s recording. A microphone on a spring clip could be attached to anything from the branch of a tree to the rim of a steel helmet. It worked on a detachable dry-battery unit which was ready wired to plug in with a single connection. The joy of this wonderful little machine was that it could be operated by anyone after half an hour’s instruction: unlike the truck unit, which needed a highly-skilled technician.

BBC midget portable disc recorder c1944,

Dr A J Croft – Licence CC BY-SA 4.0

It was also remarkably sensitive and remarkably tough. It recorded faithfully – and without damage to its delicate mechanism – anything from the full-scale screech and roar of a mortar barrage to the rumble of tank tracks rolling almost over it.

In the early days of the invasion, the B.B.C. reporters sent their discs straight back to Broadcasting House in London by special couriers supplied by the Navy and the R.A.F. Sometimes the reporters flew with them: and added to their dispatches on the way, thus bringing them right up to date. It was not uncommon, in those hectic days, to find the waiting rooms at Broadcasting House packed with weary reporters, the mud of France still on their boots, waiting to go ‘live’ on the air.

Later, complete transmission units crossed to France and followed the fighting as close as they dared. The first of these mobile transmitters, known by the code-name of M.C.O., but more affectionately by the B.B.C. men as ‘Mike Charlie Oboe’, was mounted in a 3-ton truck during the second week after D-Day. It made a perilous cross-Channel landing in a gale: but in a matter of hours M.C.O.’s aerials were up and the first dispatches were on the air, coming straight to London from a wind-swept beach in Normandy.

Much later still, when the fighting had stabilised after Arnhem, two more high-power transmitters, M.C.N. and M.C.P. – or ‘Mike Charlie Nan’ and ‘Mike Charlie Peter’ – went into service. This meant that reporters, instead of having to record on disc, could now transmit direct to London.

Thanks to ‘Mike Charlie Nan’, Chester Wilmot, one of the greatest of the radio war-reporters, was able to get a world ‘scoop’ for the B.B.C.

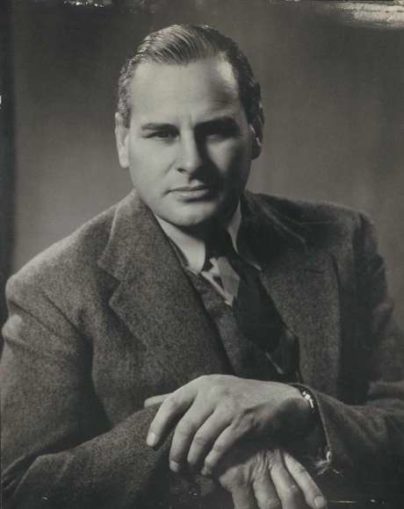

Chester Wilmot,

Athol Shmith – Public domain

On a night in May 1945 came the news of the death of Heinrich Himmler, former head of Hitler’s dreaded Gestapo. Earlier Wilmot had recorded an interview with a Sergeant-Major who was actually in the room when Himmler committed suicide. The official release of the story was timed for eight o’clock. At eight o’clock to the minute the B.B.C. was on the air – with the news and full-scale eye-witness account. . . .

But the finest technical newsgathering equipment in the world still needs the old fashioned qualities of resource and daring.

Few of the B.B.C. reporters were trained newspapermen. They soon proved that they could hold their own with Fleet Street at its best.

Guy Byam dropped with the paratroopers on the dawn of D-Day. (Later he was to be reported missing over Germany.) [ see Note 2 below ]. A few hours afterwards Howard Marshall, fished out of the sea when his landing craft sank, was sitting in a studio near Southampton recording the first eyewitness account from the beaches.

It was a B.B.C. man who got the first full story of the German surrender on Lüneburg Heath.

And one of the oddest transmissions of the war came from Chester Wilmot, who gave an exciting word-picture of the liberation of Brussels speaking on a secret transmitter fitted in a suitcase and dropped by the R.A.F. for the use of the Resistance during the German occupation.

Technically, of course, these radio reporters, like all war correspondents, were non-combatants. They did not carry arms: and under the terms of the Geneva Convention they were entitled to certain respect by the enemy.

But Total War respects nobody. And every time a war correspondent followed the troops into action he knowingly and willingly risked his life.

During the desperate fighting for Arnhem, B.B.C. reporters were in the thick of it. Day after day Stanley Maxted, a Canadian actor turned war reporter, recorded his terse, sardonic word pictures from a slit trench ringed in by the enemy. I can hear him now, signing off one despatch during the most desperate moment of the battle:

“This is Arnhem at tea-time. Only there isn’t any tea!”

Still of journalist and actor Stanley Maxted,

Unknown photographer – Fair usage

From where he watched, Maxted saw the enemy ring tightening. He had given up hope of ever getting out of the trap. But late on the afternoon of September 24th 1944, the word came through that the remnants of the battered First Airborne Division were going to pull out that night.

In a gripping broadcast from London three days later he told the full story of that desperate withdrawal.

‘We were told to destroy all our equipment with the exception of what would go into a haversack. We were told to muffle our boots with bits of blanket and be ready to move off at a certain time. When the various officers were told to transmit this news to that thin straggle of hard-pressed men around the pitifully small perimeter a great silence seemed to come upon them even in the middle of the shelling. The ones I saw just drew a deep breath and said: “Very good, sir”. Then these staring eyes in the middle of black muddy masks saluted as they always would and faded away to crawl out on their stomachs and tell their men.

‘Well, at two minutes past ten we clambered out of our slit trenches in an absolute din of bombardment – a great deal of it our own – and formed up in a single line. Our boots were wrapped in blanket so that no noise would be heard. We held the tail of the man in front. We set off like a file of nebulous ghosts from our pock-marked and tree-strewn piece of ground. Obviously, since the enemy was all around us we had to go through him to get to the River Rhine.

‘After about 200 yards of silent trekking we knew we were among the enemy. It was difficult not to throw yourself flat when machine-gun tracers skimmed your head or the scream of a shell or a mortar bomb sounded very close – but the orders were to “keep going”. Anybody hit was to be picked up by the man behind him. The back of my head was prickling for the whole of that interminable march. I couldn’t see the man ahead of me – all I knew was that I had hold of a coat-tail and for the first time in my life was grateful for the downpour of rain that made a patter on the leaves of the trees and covered up any little noise we were making.

‘At every turn there was posted a glider-pilot who stepped out like a shadow and then stepped back into a deeper shadow again. Several times we halted – which meant you bumped into the man ahead of you – then when the head of our party was satisfied the turning was clear, we went on again. Once we halted because of a boy sitting on the ground with a bullet through his leg. We wanted to pick him up, but he whispers: “Nark it – gimme another field dressing and I’ll be alright. I can walk.”

‘As we came out of the trees – we had been following carefully thought-out footpaths so far – I felt as naked as if I were in Piccadilly Circus in my pyjamas, because of the glow from fires across the river. The machine gun and general bombardment had never let up.

‘We lay down flat in the mud and rain and stayed that way for two hours until the sentry beyond the hedge on the back of the river told us to move up over the dike and be taken across. Mortaring started now and I was fearful for those who were already over the bank. I guessed it was pretty bad for them. After what seemed a nightmare of an age we got our turn and slithered up and over onto some mudflats.

‘There was the shadow of a little assault craft with an outboard engine on it. Several of these had been rushed up by a field company of engineers. One or two of them were out of action already. We waded out into the Rhine up to my hips – it didn’t matter, I was soaked through long ago – had been for days. And a voice that was sheer music spoke from the stern of the boat saying: “Ye’ll have to step lively, boys, t’ain’t healthy here.” It was a Canadian voice, and the engineers were Canadian engineers.

‘We helped push the boat off into the swift Rhine current and with our heads down between our knees waited for the bump on the far side – or for what might come before. It didn’t come. We clambered out and followed what had been a white tape up over a dike. We slid down the other side on our backsides and we sloshed through mud for four miles and a half – me thinking: “Gosh! I’m alive, how did it happen?”

‘In a barn there was a blessed hot mug of tea with rum in it and a blanket over our shoulders – then we walked again – all night. After daylight we got to a dressing station near Nijmegen and then we were put in trucks and that’s how we reached Nijmegen. That’s how the last of the few got out to go and fight in some future battle.’

***

In moments of great emotion and excitement the spoken word is infinitely more impressive than any words carefully prepared for print. The radio reporter therefore has this tremendous advantage over the newspaperman. He can express what his eyes are seeing at the moment it is happening. But sometimes that demands the special gift of cool, cold courage.

It was that quality which gave Robert Reid his chance to make radio history.

Bob Reid is a Scot who happened to be born in Bradford – that city of hard-headed, clear-thinking men – and went to the same school as J. B. Priestley.

Before he joined the B.B.C. he had been a newspaperman all his life, first on the Yorkshire Observer, then on the News Chronicle, where for a time he was Northern News Editor.

He is a small, square-built little man, with a pugnacious approach to news and a very warm heart. He started with the B.B.C. as a Press Officer in 1939 and became one of radio’s first war correspondents.

Like all born newsmen he has a flair – a sort of sixth sense – for knowing where the news will break next.

One morning in Paris, in that wonderful August of 1944, Reid was waiting in the great square outside Notre Dame.

He had a very special assignment. He was waiting for General de Gaulle to review the men and women of the Resistance who had fought so long and so bravely for liberation and were now to be publicly honoured for it.

But – though Reid didn’t know it – there were others waiting for de Gaulle that morning. They were hidden up there among the gargoyles of Notre Dame, with rifles and machine guns trained on the General.

And as that tall, scholarly figure walked into the square, as Reid lifted his microphone to record, they opened fire. And this is how history caught the echo of those shots:

“Immediately behind me through the great doors of this thirteenth-century cathedral I can see, in this dim half-light, a mass of faces turned towards the door. Waiting for the arrival of General de Gaulle, and when the general arrives, this huge concourse of people both inside and outside the cathedral, they’ll be joining in a celebration of the solemn Te Deum in the mother church of France.

“You may be able to hear that I’m talking amid the noise of tanks; now those are the tanks from General Leclerc’s Division, the boys who were instrumental in punching a hole right through the German defences outside Paris and into the heart of the capital. I believe the original intention was that these tanks were going to be used as a guard of honour, but thousands of Parisians have now climbed onto the top of those tanks and I believe I can only see one track of the end tank. The police are having a bad time trying to keep the crowds back – they’re all trying to press right through to the cathedral.

“Immediately in front of me are lined up the men and women of the French Resistance Movement; they’re a variegated set of boys and girls – some of the men are dressed in dungarees, overalls, some of them look rather smart, the bank-clerk type, some are in very shabby suits but they’ve all got their red, white, and blue armlets with the blue cross of Lorraine and they’re all armed, they’ve got their rifles slung over their shoulders and their bandoliers strapped around their waists.

“And now here comes General de Gaulle. The general’s now turned to face the square, and this huge crowd of Parisians – (machine-gun fire). He’s being presented to people – (machine-gun fire) – he’s being received – (shouts from crowd and shots) even while the general is marching – (sudden sharp outburst of continued fire) – even while the general is marching into the cathedral . . . (break on record).”

The commentary broke abruptly there because in the panic that followed, as people rushed blindly for shelter, Reid was bowled over and his microphone lead broke.

But somehow he butted his way up again and followed the General as he walked head high, shoulders flung back, into the hail of fire pouring at him from one of the galleries up near the cathedral’s vaulted roof.

Miraculously the General was unhurt. Miraculously too, Reid got his midget recorder into action. And a few minutes later he was squatting cross-legged on the floor of the cathedral recording that amazing scene the people of Paris, with the General at their head, standing up in their ancient church to sing a solemn Te Deum; while still the blinding flashes of the shots lit up the dim interior and chips of masonry splintered down over them.

That disc is now carefully preserved in the B.B.C.’s library. It must be one of the most extraordinary commentaries ever recorded. “It was the most remarkable example of courage that I’ve ever seen,” says Reid, remembering.

A tribute equally deserved by the man who put it on record.

Notes

1 Reginald William Winchester Wilmot (21 June 1911 – 10 January 1954) was an Australian war correspondent who reported for the BBC and the ABC during the Second World War. After the war he continued to work as a broadcast reporter, and wrote a well-appreciated book about the liberation of Europe. On 10 January 1954 he was killed in the crash of a BOAC Comet over the Mediterranean Sea, the first of two Comet crashes that year (courtesy Wikipedia).

2 Guy Byam-Corstiaens was a British journalist and sailor. He served in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve and was one of only 68 survivors of the 254 crew of HMS Jervis Bay which was sunk in November 1940 in the North Atlantic. Byam was killed when the plane from which he was reporting, the Rose of York, was shot down over Germany during a daylight air raid on Berlin in February 1945. He was one of two BBC reporters who were killed during the Second World War (courtesy Wikipedia).

3 Stanley Maxted (21 August 1895 – 10 May 1963) was a British-Canadian soldier, singer, radio producer, journalist and actor. He worked for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) and later for the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) as a war correspondent during World War II. Following the war, he became an actor and appeared in a number of films between 1949 and 1958 (courtesy Wikipedia).

4 Robert Reid’s live commentary on the attack on General De Gaulle can be heard here.

Jerry F 2022