THE PORTUGUESE LANGUAGE AND DISCOVERY OF THE ARCHIPELAGO

Descartes is famously quoted as having said “Cogito, Ergo Sum”. His remark was first published in French to reach a wider audience- “Je pense, donc je suis”. The original Latin expresses in only three words how our inner selves relate to the outer world. We are conscious of our own existence through our brains but can understand the external world and communicate with others only through our five physical senses of touch, taste, smell, sight and sound.

Portuguese must be one of the most difficult European languages to learn and speak fluently because the sounds used are distinctive and variable. In written form the same letter can represent a different sound depending on others nearby, or it can have an accent above or below. Still more different sounds are represented by pairs or even triple letter combinations (dipthongs and tripthongs) and those can vary depending on where they appear in a word, or a word in a sentence. Many letters and combinations have a nasal sound similar to that produced by pronouncing the spelling in an English way whilst pinching ones nose. Some sounds are not used in English at all. That can lead to considerable confusion when attempting to write Portuguese names or words in English which is why one will often see Portugal’s capital city written as Lisbon on English Maps but as Lisboa on Portuguese ones, and the world’s fourth largest city written either as São Paulo or San Paulo.

The Portuguese word AÇORES is another example. Some Americans who spell the name with a letter Z pronounce it as AY-ZORES and some English who spell it the same way, say AZ-ORS. The Portuguese themselves say it more like ASS-OREES but that too can have a great deal of variation depending on whether the speaker is European, Brazilian, a native of the archipelago, or from some other Portuguese speaking country.

The name is often thought to be derived from that for a medium-sized bird of prey found there in the 15th Century when settlers described them as Açors, the Portuguese word for the species we now call Northern Goshawks. Modern Taxonomists consider the birds were more likely to have been a sub-species of the Common Buzzard. The differences between various Birds of Prey can be a little confusing to a general reader and this birdfinding.info site may help (if only by increasing awareness of how many species there are).

The Coat of Arms of the Islands and Promotional Materials for tourists have gone with the flow and feature Buzzards rather than the species from which the islands take their name. Perhaps Goshawks are sometimes found there. The archipelago is after all very well-situated as a resting place for east-west migratory species and Açors are common in both Europe and North America. However, both Goshawks and Buzzards seem to mostly migrate north-south rather than east-west so I’m not sure about that and leave the question to be debated or settled by others more knowledgeable than I.

When and how the islands were first discovered is also a topic whose true origin is probably lost in the mist of time. Legends and stories of islands in the Ocean beyond the Pillars of Hercules at the western end of the Mediterranean existed in classical times.

Plato wrote about the lost island of Atlantis in 360 BC; Pliny the Elder who lived in the first century AD, gave at least one of the Canary Islands it’s latin name, Canaria Insula, because he had heard large numbers of dogs were found there. Plutarch, also writing in the first century records a story of an hearsay report there were two islands about 10,000 furlongs off the coast of Africa and close to one another. It is supposed this was a reference to Madeira and its small neighbour Porto Santo.

It seems likely the Canaries and Madeira were first discovered, or re-discovered, by the Portuguese and Spanish in the late 14th and early 15th centuries because their existence was already known about or rumoured and the development of Caravel designs using lateen sails (ref SMLA, part 19) made it possible to sail to them and back again.

There are records showing the Canaries were being visited and colonised by 1410 with Portugal and Castille vying with one another for possession – a contest won by Castille. It is also recorded that Portugal had discovered and claimed Madeira and Porto Santo by 1420.

It is uncertain exactly who discovered the nearest Azores Island and when. Its possible a Portuguese Pilot named Diogo de Silves did in 1427, when blown off course on a voyage to Madeira under his own command. Others think that de Silves was actually the navigator during a voyage commanded by Goncalo Velho Cabral. De Silves claim is based upon his name having been been deciphered on a map produced in 1439 but partially obscured by an ink blot spilled upon it later. All that seems certain is that Cabral’s was the name the Portuguese Crown registered in 1432 as the discoverer and first Captain of the Island responsible for colonisation and maintenance of order in the king’s name (a role the English called “Governor”).

WHERE ARE THE ISLANDS ? – AND – THE VOYAGE PLAN

Santa Maria lies a little less than 900 miles west of Lisbon and there are another eight islands in the archipelago. The ninth, Flores, is another 400 miles or so west of Santa Maria and the nearest land west of that is New York at about 2,000 miles, though Newfoundland to the WNW is closer at about 1,250.

My plan for 1998 was to visit all the islands and return to UK via the west and south coasts of Ireland. The latter would entail a passage from Flores to Galway of about 1,400 miles, making a total distance across the Ocean of about 3,000 miles. I reckoned that would be enough to give me the confidence to go farther in later years or scare me away from the idea of long-distance sailing altogether.

I made a number of maps illustrating my plans using the same style as those included in the first Series of SMLA but have produced a modern one for this article –

Although I had sailed alone the previous year, when planned crew hadn’t turned up, I didn’t want to repeat the experience from choice and sought companions for each leg of the voyage, with crew changes at Corunna, Lisbon (Cascais), Horta (town on Faial at the centre of the archipelago) and Galway. The easiest to arrange were the legs from Falmouth to Lisbon and the return from Galway. Pip, who had come with me to Copenhagen the previous year was keen on the outward leg from Lisbon and was joined (when planning) by Tom from the USA who responded to an ad in the yachting press, but generating interest in the return from the Azores to Galway was more difficult.

It was only a short time before departure when arrangements for that critical leg were resolved with Tom agreeing to stay on for longer and Alex, a friend of Janet’s who had come with me from Oslo to Bergen in 1997, also confirming his interest.

Because of the late discussions and distances from their homes it wasn’t possible to arrange a shakedown trial with either Tom or Alex before their planned arrivals for the voyage itself. That turned out not to matter in Alex’s case and he came with me several times in later years when Alchemi was in the Caribbean. It was generally satisfactory in Tom’s case too but a less happy arrangement and he didn’t come again after this year’s voyage.

To set the scene its worth spending a little space on the general climatological patterns in this part of the world.

The entire voyage lay in a box defined approximately by the co-ordinates (37 N, 25 W) and (53 N, 5 W). Within that box there is little effect from major oceanic currents but significant differences in prevailing winds and surface currents blown by them. Those are largely determined by the following patterns –

There is a fairly static high pressure region over the Azores themselves with the consequence winds near the islands are mostly light and variable.

Westerlies prevail to the north and often have a southerly component near the British Isles.

In summer the centre of the Iberian peninsula can become very hot leading to low pressure with a tendency for winds to become anti-cyclonic blowing south on the Atlantic coast and north up the Mediterranean one. Combined with the easterly edge of the Azores High that can generate very strong and consistent northerly winds called Nortada blowing south down the coast of Portugal.

The Nortada are known to English speakers as “The Portuguese Trades” and their existence is why sailing craft going to Northern Europe from the Mediterranean, or Madeira and the Canary Islands, usually find it quicker to take the longer route via the Azores and then go East on the westerly winds thereafter.

STARTING POINT FOR THE OCEAN PASSAGE

My plan for the 1998 voyage recognised these patterns but in this article I’m going to start my account at Cascais which is a seaside town at the mouth of the River Tagus with Lisbon city centre about 13 miles inland.

I shall be using as many of my own photos as possible for illustrations, data from my log-sheets (SMLA, part 8) and text from my original Journal for the narrative. Here’s a photo of Cascais Harbour and some opening remarks from my journal. –

Cascais is a much more cosmopolitan town than others seen during the entire voyage. It is quite compact and combines the attractions of fine buildings, local life, and seaside resort for the well-to-do from Lisbon as well as International Tourists.

I was able to buy Camping Gaz and engine lubricants locally but not a manual pump for removal of used engine oil. The Ironmonger who supplied the Gaz assured me one would be easily available at a chandlery in Lisbon, conveniently close to the rail terminus, and advised me to go today because “tomorrow will be a City Holiday”. At this point another customer said “It’s not possible today – there’s a railway worker’s strike”. The ironmonger just grinned and commented “A strike today and a holiday tomorrow – that’s Portugal for you”.

Transfer of departing crew and new arrivals went as planned with a lot of dinghy work to and fro ferrying people and their luggage between yacht and shore. On one shore outing I found the local Clube Naval and learned diesel and water could be obtained there but only at high water when tied-up at the harbour wall.

However, looking at the wall through binoculars at low tide the next day I could see rocks nearby and what looked like a slab of concrete leaning high up the wall right by the diesel pump.

I don’t remember if I fully explored the arrangements, and wonder now whether there was access inside the wall as well as outside. At the time I was perturbed by the hazards. Anyway, I also thought a short day-sail was needed to help the new crew settle-down and so decided to look for fuel and water by heading towards Lisbon. (I think nowadays there is a modern marina at Cascais and I’ve no doubt that includes good access to all facilities).

We set off motoring and found our way around the sand-banks and past a fort guarding approaches to the river Tagus.

After entering the first yacht marina on the northern shore we were redirected to the next one upriver between the impressive Belem Tower and a large Concrete Sculpture depicting a Caravel and famous Portuguese Navigators. Here in Belem marina we found both fuel and water. We could have stayed overnight if I had not been concerned by the manager’s warning – “You might just touch bottom at low tide”.

Here’s a photo of the north shore of the Tagus near Central Lisbon with the Belem Tower in the foreground, the Monument to the Navigators at mid-distance and the bridge behind carrying the main road from the City over the river to the south –

The Tower was built between 1516 and 1519 to supplement Lisbon’s defences that had previously relied on fortresses at Cascais and a sister town on the south bank of the river’s estuary. It is now classified as a World Heritage Site.

The Monument is a sculpture completed in 1960. It has 16 historical figures in profile on each side. Those on the West are mostly the Navigators themselves – Bartolomeo Dias, Vasco da Gama, Ferdinand Magellan, and so on; the East face mostly commemorates missionaries, cartographers and writers; both faces also show various Royal personages of the times.

Here is a closer look at the monument –

The wind had been strong all day as we motored upriver and was still blowing hard after filling tanks. I decided to sail back to help remind Pip and familiarise Tom with controls for managing sails, laying the anchor and so on, and because of shallow water in the marina. We would anchor again at Cascais for the night and set off for Santa Maria the next day.

That’s what we did on a fine reach with two reefs in the main and the staysail but no jib. The wind was from the NW gusting to 35 knots, but the waves were moderate because we were so close to land the whole way.

That evening we thought about and discussed the broad outlines of the navigational plan we should adopt for the passage to Santa Maria.

We hoped to maintain an average speed towards our destination of at least 4 knots and didn’t expect to maintain more than 6. Those are roughly equivalent to a minimum of 90 miles every 24 hours and a maximum of 140. Those speeds implied a time required for the passage of somewhere between 6 1/2 and 10 days. Of course this was a rough and ready estimate because it made no allowance for the distance sailed being greater due to wind or current direction and strength, or for slower speed due to sea-state (high speeds in steep waves can be very uncomfortable and are sometimes reduced for that reason).

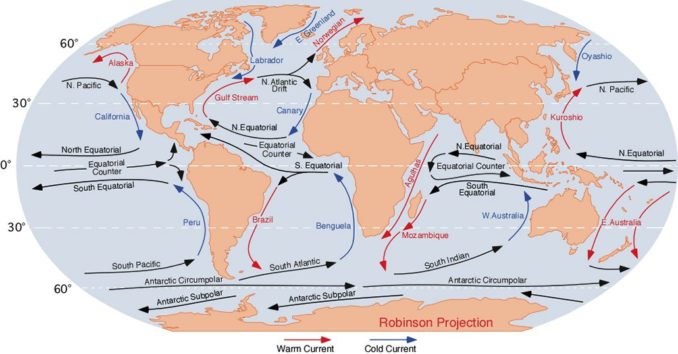

As explained earlier, we didn’t expect any strong currents but did recognise there is a southerly tendency at about 1/2 knot for some distance off the coast of Portugal. That’s present because of the North Atlantic Circulatory system that is one of the gyres formed in the major oceans of the world. These are induced by the sun’s radiation but with movement of water blocked by the continental land-masses. The clockwise rotation in the northern hemisphere and anti-clockwise in the southern is caused by the earth’s spin on its own axis. (Similar effects occur in the atmosphere but are less noticeable due to temperatures of the land and air above it responding much more rapidly to changes in solar radiation with those responses dominating air flows, especially when some distance from coasts).

The gentle southerly stream would correspond to a boat movement of about 12 miles in every 24 hours when near the coast and less with distance farther out to sea. We hoped to counteract that by steering about 7 or 8 degrees north of the shortest path whilst maintaining our estimated speeds through the water. Achieving that would be highly dependent on wind strength and direction so we’d need to monitor our actual position as we went along and make adjustments accordingly.

This sort of assessment wouldn’t do for racing sailors who would almost certainly want to carry out a much more detailed analysis but hey, we were cruisers making the journey to satisfy our curiosity about new places and for our relaxed enjoyment – not to compete or set records. Furthermore, we saw little point in leaving first thing in the morning as there was in any case an uncertainty of 3 or 4 days in our arrival day and time.

To be continued ………………..

© Ancient Mariner 2022