In my introductory article we saw that by the beginning of the 19th century the flintlock was firmly established as the state-of-the-art means of ignition in military and sporting firearms. In this article, we will discuss how the flintlock mechanism works and what it is like to shoot.

I currently own two flintlock pistols one of which is an original and the other a modern, Italian-made reproduction. The original pistol, which is the oldest piece in my collection, was made by Barwick of Norwich. According to the trade directory, the Barwick brothers were in business in the city between 1796 and 1804 so the pistol can be dated with confidence to circa 1800. It is difficult to say with any certainty what classification it falls under. Was it, for example, an ‘officer’s pistol’ purchased by a serving army or naval officer of the period for use in the service of His Majesty King George III or was it a civilian weapon used for personal protection against footpads or highwaymen? Could it once have been one of a pair of duelling pistols as identical pistols to this from the same maker have since appeared in matching pairs at auction? A cased pair of flintlock duellers by a famous maker is every gun collector’s Holy Grail.

The Barwick has a .616” dia. smooth bored (i.e. unrifled) barrel making it a ’20-bore’ in the old calibre classification. This simply means that it fired a round ball, 20 of which could be cast from one pound of lead so the lower the bore number, the larger its diameter. I no longer think that it is an officer’s private purchase as when compared with military pistols of the period, it is too light in weight to have stood up to the rigours of service use. As a personal protection weapon it is too long and unwieldy to have been carried concealed in an overcoat pocket but it could certainly have been used for home defence or for target shooting/duelling. Whatever its original purpose, to me it is a thing of great beauty and I get a thrill simply from holding this Georgian artefact and imagining what life and society must have been like when it was originally purchased.

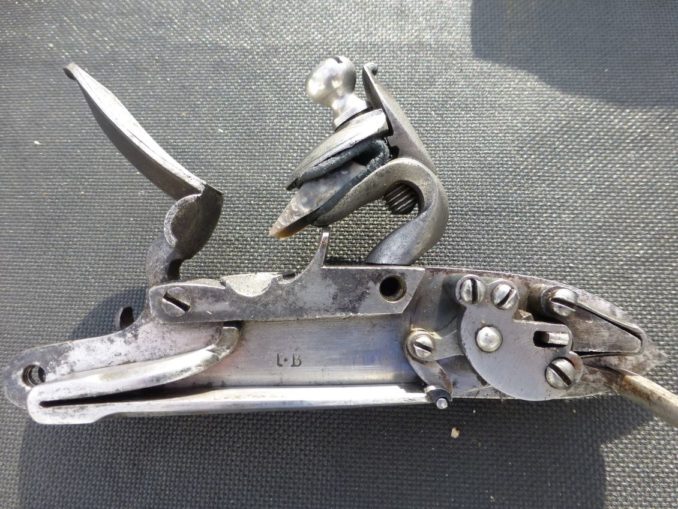

When the pistol is stripped to its three main component assemblies we have the ‘lock’ which is the mechanism on the side that produces sparks to initiate the explosion of the powder charge; the ‘stock’ or wooden handle into which the lock and trigger mechanism are fitted together with the ‘barrel’. This is where the expression ‘lock, stock and barrel’ meaning the whole kit and caboodle originates.

Turning our attention to the lock, we can see that it comprises an ‘S’ shaped arm that holds a knapped piece of flint clamped tightly between leather-lined jaws. This is known as the ‘cock’. Opposite the cock is a smooth and slightly curved piece of hardened steel that the flint strikes as it descends when the trigger is pulled. This is the ‘hammer’ or as it is more commonly known nowadays, the ‘frizzen’. As the flint scrapes down the frizzen it causes the latter to pivot towards the muzzle end of the pistol exposing the priming powder in the pan below. At the same time, tiny slivers of steel are being shaved off the frizzen by the sharp, hard flint which, glowing white hot due to the friction, fall in a shower of sparks into the now open pan igniting the fine priming powder which then flashes through the touch hole setting off the main charge. The rapidly expanding gases produced then propel the heavy lead ball out of the barrel with lethal force.

Whilst it cannot be compared with the exquisite workmanship of the top London gunmakers of the age such as Mortimer, Twigg, Egg or Manton, the Barwick lock nevertheless has a couple of features that mark it out as being of high quality. The small projection in the lockplate to the rear of the cock is the sliding safety catch which can be engaged when the cock is drawn back to the first detent position making it possible to carry the weapon safely at ‘half-cock’. Without this the pistol might accidentally ‘go off at half-cock,’ something that is definitely to be avoided but which must have happened from time to time otherwise the expression would not have entered common parlance to mean something taking place that hasn’t received adequate forethought or preparation before being actioned.

If you look closely, you will see that at the end of the external frizzen spring there is a small roller. This ‘roller frizzen’ reduces the friction when the flint falls ensuring that the frizzen snaps back more rapidly to expose the priming powder in the ‘semi-rainproof’ pan for faster, more efficient ignition.

The best gun flints are jet black and come from Brandon in Suffolk where they have been mined and knapped since Neolithic times. A visit to the 5,000 year old flint mine nearby at Grimes Graves, Norfolk is well worth a detour if you are in the area. Flint knapping is a dying art and people I know who have tried to master it in the interests of economy say that it is so frustratingly difficult that they’d much rather buy their gun flints ready-made. Occasionally flints come onto the market that have been salvaged from shipwrecks as they suffer no detriment from centuries of immersion in sea water and are still as sharp as the day they were made. It is impossible to say how many shots you can get from a flint as they are all different and annoyingly inconsistent. Your flint may be sparking perfectly for shot after shot and then it will inexplicably fail, typically just as you are taking an important shot, much to the merriment of onlookers.

The oil-finished and finely hand-chequered, full length stock is carved from best English walnut and fitted with an engraved, pineapple trigger guard. Pineapples were very popular status symbols in the Georgian period and were often used in architecture as a decorative motif. Under the barrel are two ramrod pipes that hold the original ebony-tipped ramrod which is fitted with a worm for ‘drawing the charge’ or removing balls and wadding from the barrel.

The octagonal, sighted barrel is attached to the stock by means of a hook breech and two wedges. It is slightly ‘swamped’ meaning that it is thicker walled at the muzzle giving it better balance so that it comes to the aim quickly and naturally. A highest quality barrel of the period would have had a gold or platinum-lined touch hole to prevent erosion in use that would lead to excessive discharge from the vent causing reduced power and impaired accuracy.

Shooting the Barwick pistol

The Barwick is a beautiful example of the gunmaker’s craft and a delight both to own and shoot. It is surprisingly light and so exquisitely balanced that it feels like an extension of one’s arm and comes to the aim naturally. After much experimenting, I load it with a 40 grain charge of fine black powder under a patched round ball. We shooters still use old-fashioned Imperial measurements so I should explain that there are 7,000 grains to the pound and therefore the propellant charge is 40/7000lb. With all muzzle-loaders, the projectile must, except in rare circumstances, be smaller than the bore diameter so as to facilitate loading, particularly when the barrel is fouled with gunpowder residues from previous shots. To take up this ‘windage’ between the undersized ball and the barrel, we use pieces of lubricated, densely woven cloth such as Irish linen of various thicknesses in the form of circular or square ‘patches’ that enclose the ball as it is rammed down on top of the powder charge. The patch centres the ball in the barrel and minimises leakage of expanding gases past the ball ensuring that it flies true as it leaves the muzzle, dropping off the ball shortly after it leaves the gun. Used patches picked up downrange are useful in the diagnosis of loading problems.

One of the frustrations of flintlock shooting is the occasional and sadly inevitable occasion when the powder in the pan ignites but for some reason doesn’t set off the main charge. This is known as a ‘flash in the pan’, another expression that is still in common use. When this happens, the gun must be kept pointed at the range backstop for 30 seconds in case delayed ignition takes place. After this safety period has elapsed, the gun may be primed again after first making sure that a) you remembered to put powder in the barrel before the patched ball was loaded (more likely to happen when enthusiastic bystanders are asking questions while loading is taking place) and b) you prick out the touch hole to ensure that it is not obstructed.

People often ask me if flintlock pistols are accurate and this is a difficult question to answer. The answer has to be yes qualified by in the hands of a skilled shot and provided they are loaded correctly and consistently. At my two clubs we can only shoot pistols at 25 or 50 metres range, distances at which these old pieces were never intended to be used as they were close range, self-defence weapons for the most part. Shooting any pistol well is extremely difficult but with a flintlock smoothbore it is unbelievably frustrating. I do occasionally hit the target board with the Barwick but only rarely. At close quarters though this ancient pistol would still be deadly, even in my hands.

One learning point that has come about from shooting the Barwick is that our modern practice of shooting tightly patched balls in flintlock pistols could not have been the norm in the early part of the 19th century. I say this because ramming a tightly patched ball down even a smooth bored barrel, particularly when fouled from previous shots, takes considerable effort requiring the use of a ‘starter,’ a stout ramrod and sometimes a wooden mallet. If you look at the ramrod provided with the Barwick, you will see that it is very flimsy and has a sharply pointed worm tip. This could only have been used between thumb and forefinger so my contention is that this pistol must have been designed to be loaded with an unpatched ball of slightly less than muzzle diameter. This was borne out one day when, after a frustrating session when I couldn’t even hit the 2ft x 2ft target board at 25 metres, I misloaded a ball so that the patch ended up wadded on top of it. Amazingly, when I shot it like this I hit the target but it was probably just a coincidence.

This beautiful pistol which was made around 220 years ago still does the job for which it was originally intended. It shoots a heavy chunk of lead with considerable force and is still more than capable of ruining the day of anyone unfortunate enough to stand in its way. You should never underestimate the potency of obsolete firearms.

Conclusions

By the beginning of the 19th century, the flintlock mechanism was at the peak of its development and in use in both military and sporting firearms worldwide but it was not without its problems. In common with all muzzle-loading firearms and particularly those with rifled barrels, they are slow to load and need constant attention to detail to maintain their efficiency. Firstly, the flint must be sharp and located correctly and firmly in the cock to ensure that it strikes the frizzen in the right place and at the correct angle so as to produce sufficient sparks to ignite the priming charge. Gunpowder residues attract moisture, so keeping the pan, frizzen and flint clean, and thus moisture free, is imperative. The priming powder must also be correctly positioned in the pan and in just the right quantity to suit the particular gun and the touch hole must be kept clear of obstructions.

The biggest problem with the flintlock for sportsmen and women however is that the flash and smoke as the priming powder in the pan ignites can startle game. It is this coupled with the short and variable delay between flash and ignition that makes shooting moving targets such as flying birds very challenging indeed with a flintlock.

In the next article we will look at a development that solved these problems and revolutionised the firearms industry; the invention of the fulminate percussion cap.

© Tom Pudding 2019

Audio file