I did not come to the Harry Potter books early and, in truth, I did not come to them easily. One of the gifts that old age bestows is the ability to make up your mind about something without ever actually trying it, and while my wife and the rest of our family and friends had been raving about the books for years I dismissed the burgeoning franchise with a sneer of academic hauteur and muttered darkly about plagiarism.

When I did finally settle down with the first volume I made it part way through the opening chapter before actually throwing the book across the room in disgust. It was precisely as I had anticipated: a huge and unapologetic exercise in cobbling together a ragged patchwork from the Fantasy and the Public School genres of children’s literature.

Mrs B spoke soothingly to me and mopped my fevered brow, and in a short while I was ready to try again. I found them to be, when read for their own sake, perfectly amiable and enjoyable examples of fiction for children, if a little po-faced.

Clearly the work of a gifted storyteller, the story arc over seven (I think) volumes is consistent and credible, and Rowling managed the neat trick of making each book a little more ‘grown up’ that its predecessor in synchronization with the advancing age of her audience. You might have read the first book at the age of perhaps eight and the final volume would have been published when you (and Harry) were teetering on the brink of adulthood, and trying in your clumsy adolescent way to deal with the new complexities of life. For kids reading the series as it was published, it must have been very easy indeed to identify with Harry and his chums.

And I will go on record as saying that Rowling handles this aspect of her story particularly well. I deplore vulgarity, and the tendency of modern authors to confuse pornography with verity, but to ignore the development of adolescence in this respect would have at the very least been stilted and awkward. Rowling deals with it discretely and tactfully, and at the risk of sounding like a Victorian maiden aunt, ‘tastefully’. She does so also, I think, with a gentle good humour. She does not receive enough credit for this, and it is one of the facets that raise her work above the average.

Which is just as well, for in the originality department Rowling is completely and utterly null and void. Now this is not a criticism. Nihil sub sole novum (and the Romans themselves were borrowing from the Ancient Hebrew priestly writers there) and “the new is simply that which has been forgotten”, and all the rest of it.

Rowling plunders her sources, which range from Hesiod to Mallory Towers, with a gay abandon which is rather admirable. She is clearly a woman of considerable erudition, and romps her way from Greek Mythology to the social structures of Nineteenth Century public schools with a confidence which is utterly disarming. And this is all precisely as it should be.

The only thing in the Harry Potter books which you will not find anywhere else are the rules of the game of Quidditch. Which word, I now notice, has insinuated itself into my laptop’s dictionary and did not require me to override autocorrect. This is how you know you’ve made it in the Literary world.

The whole Quidditch thing is however merely a nod in the direction of Cricket, the complex and beguiling minutiae of which so deeply obsessed the writer of every boy’s book from dear old Tom Hughes to Anthony Buckeridge. Sorry, Ladies, but hockey is just a bunch of chunky girls running about and biffing a ball with a curved stick. Even Angela Brazil couldn’t get herself worked up over whatever the Hockey equivalent of Wisdens may be.

But none of this matters. The story is the thing, and Rowling is a master of the craft. All else is scenery, stage furniture and props. Rowling handles them all well, and builds with them a coherent and distinct world. An exegesis of the Potter books would, and undoubtedly already has, provided many an indigent Eng. Lit. undergraduate with profitable mining through a BA and beyond. Assuming that they were aware that Rowling was not the fountain of origin of these cultural appurtenances, of course.

Recently, of course, Rowling has drawn the ire of the Left. Originally for uttering the worst of heresies: that there are biologically only two genders. The enunciation of The Truth That Cannot Be Named predictably, and with the suddenness of an Elizabethan Mephistopheles springing from a stage trapdoor, caused her erstwhile friends in the Media-Political Nexus to turn against her.

She has effectively been un-personed from the creative entity that she brought into being, and which sails on without her. Many of the cast, especially those who made their fortunes as children on the back of her work, have not been slow to join in the chorus of repudiation. It has been a typically less than edifying spectacle of eager public conformity to political correctness and ideological orthodoxy. And it looks as though the process is not yet over, for the critical analysis from a hostile perspective seems to have begun.

A chap called Jon Stewart, about whom I know little other than that he is apparently Jewish and shares his opinions with an expectantly eager nation via a regular podcast, has accused Rowling of inserting into the Potter Universe an anti-Semitic stereotype. That is to say of the Jews as hook-nosed and physically repellent, as avaricious and with a concomitant tendency to gravitate to those positions in the economy where they can enrich themselves most easily and exert an undue and malign influence on the body politic. And in Rowling’s books the perfidious Tribe of Judah sneak in under the guise of the race of Goblins. According to Mr Stewart.

Fair enough, but let us have a look for ourselves. We are all, at this late stage in our acquaintance, big enough and ugly enough to deconstruct a literary text without having to rely on the say-so of Mr Stewart and his ilk. Or at least I fervently hope that to be the case.

At first blush, the chap does seem to have a point. In one memorable scene from the first film, Harry goes to Gringotts Bank. Gringotts is run by goblins and is explicitly the sole financial institution in the wizarding world, and thus the goblins hold a financial monopoly. Inside he is greeted with a scene of serried rows of lecterns at each of which sits a goblin dressed in a frock coat and scribbling away with a quill.

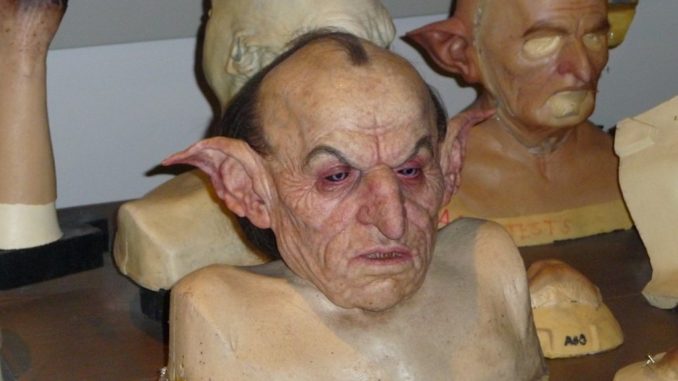

The goblins are humanoid but repulsive in appearance, with hooked and exaggerated noses and sallow skin. They are taciturn and sullen to those not of their kind, and they only grudgingly part with the deposit that is rightfully Harry’s. It does rather look as though Mr Stewart was onto something after all. Cor blimey. Stone the crows.

But wait! The Goblins are small, perhaps under three feet which I take to be considerably below the height of the average Jewish person. They also have outsized and pointed ears. Of course, if you prefer to introduce your anti-Semitism subliminally, you would throw in a few aberrant details to provide a little credible deniability should the politically righteous mob ever come calling. You can argue the toss either way here and the case, as Scottish Law says, is ‘not proven’.

Is miserliness a quality exclusively ascribed in literature to Jews? If it is, then we have Rowling bang to rights. Certainly Shylock, Fagin and Marlowe’s Barabas fit the bill. But poor old Silas Marner was cast out from his congregation under the false allegation of church funds, Volpone may perhaps be a Pythagorean but he is not Jewish; and so on through Scrooge, Anthony Chuzzlewit and Bennett’s Henry Earlfoward. Literature is replete with non-Jewish misers. To ascribe that characteristic to a fictional creation is not to necessarily be thinking of the Jew as your paradigm, either consciously or subconsciously. I’m as tight as a gnat’s chuff, and I’m not Jewish: it is merely part of the human condition.

If we look at the idea of Goblins themselves, we will find that Rowling has stayed very true to her original sources. We will also find that Goblins are old, very old indeed, and that they predate the emergence of European anti-Semitism during the Middle Ages by some several millennia,

The Ancient Greeks knew them, and called them Κόβαλοι – Koballoi. They were mischievous and acquisitive little sprites, who once robbed Hercules and delighted in generally perplexing the human race. They migrated to Rome, where they were known as Coballi and where they jostled with the Lares and Penates for a share of warmth at the hearth and a tithe of the household produce. By the fifteenth century, they had migrated to Northern Europe. The branch that settled in Germany discovered an affinity for mining and metallurgy and were known as Kobolds. Those that settled in Britain adopted a more bucolic lifestyle and were called Goblins, of whom Puck and Robin Goodfellow are the prime exemplars.

In appearance they are much as Rowling describes them: short in stature, humanoid but clearly not human and thus ill-favoured in our eyes. Thus Goblins have been, thus they are and thus they will always be until Time Immemorial. All Rowling did was to modernise the idiom a little.

Of course I doubt that this line of reasoning would sway Mr Stewart one iota, and I rather believe that he would be mildly surprised to learn that Goblins have any antecedents further back than the publication of the first of Rowling’s books. If as a child Mr Stewart was only allowed to read from a canon of right-on literature approved by his achingly progressive parents, I would not be at all surprised. And that is a shame, if for no other reason that a joyless childhood produces joyless adults like Mr Stewart.

I doubt that this is over for Rowling. The likes of Mr Stewart do not lack tenacity. Even now he is presumably beavering away in pursuit of his thesis that the Harry Potter story is a rework of The Protocols Of The Elders Of Zion and that Rowling is a Jew-baiter of the magnitude of Julius Streicher, but with nicer manners.

Of course, the magnitude of the chuztpah of the Leftwaffe in chucking allegations of anti-Semitism around the place almost defies human comprehension. But that is, perhaps, a story for another day.

© bobo 2022