My uncle was a staff reporter for the Manchester Evening News from the late 1940s until his death in 1973. The following is from a series of articles in which he describes his extensive visit to China in 1973 and provides a fascinating insight into what life was like in China 50 years ago. It is reproduced with kind permission of the Manchester Evening News.

My uncle was a staff reporter for the Manchester Evening News from the late 1940s until his death in 1973. The following is from a series of articles in which he describes his extensive visit to China in 1973 and provides a fascinating insight into what life was like in China 50 years ago. It is reproduced with kind permission of the Manchester Evening News.

One for all, all for one

Tang Man-Liang is fish breeder. Which means that he belongs to one of the oldest crafts in China. Generations of Tangs have dug the fish ponds and stocked them every spring with fry and then netted the full grown crop from each pool in rotation from April until November. So it has been every year since the beginning of recorded time. Which in China is a pretty long time ago.

Tang learned his craft from his father, who worked this Hola fish farm in the years before Liberation (1949), when all fish farms were owned by landlords, who had the fish breeding monopoly. Although there was no better fisherman in Hola, says Tang, he was still hired by the day. And when times were bad he was put off without warning. He had no home of his own and lived in a tied cottage that belonged to his employer. Often he would have to go in debt to him and work for nothing to pay the rent.

Tang has done rather better for himself. At 28 he is administrator of the Hola brigade fish breeding team. He is responsible to the brigade, and through the brigade to the commune, for 402 other fish breeders and 162 fish ponds of various sizes. And he does have a home of his own. It is the same house with that ancient dragon boat roof, where his father’s landlord used to live.

The communes

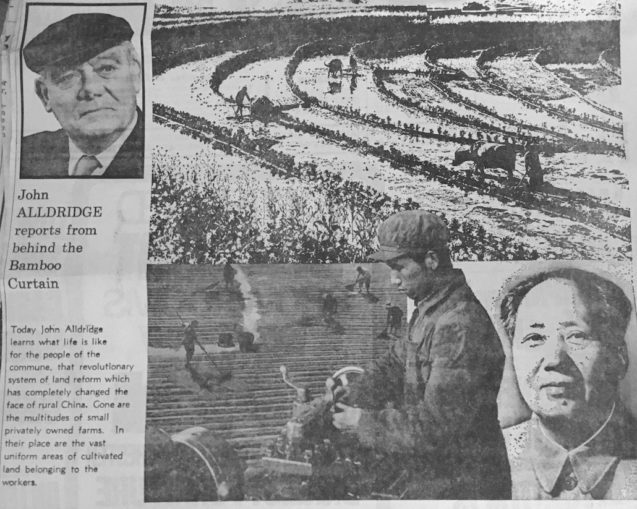

And from Tang for the first time I learned about the communes, that revolutionary system of land reform which has completely changed the face of rural China and turned it from a patchwork of multitudes of tiny privately owned farms, barely living from hand to mouth, into vast uniform areas of cultivated land belonging to no one but the people who work it.

The Hola brigade of the Hola people’s commune represents 986 households, with a total population of just under 4,000; or about the size of two small English villages. Of these 4,000, some 1,850 – 552 of them women – work for the community in one of several very definite ways. There are 18 separate production teams: eight producing grain, three engaged in fish breeding, six in farming and collecting silk worms from the myriad mulberry trees you see everywhere, and one coaxing pearls from reluctant oysters kept in tanks for two years at a time.

For those who can’t find work in any of the regular work teams there are two small processing workshops, where they can cobble rubber soles for shoes, or embroider handkerchiefs for the factories in the nearby town of Wushi.

Nothing wasted

Even the old people aren’t idle in Hola. There is a day nursery where the able-bodied grannies can be kept busy; and plenty of rabbits for the old gentlemen to look after. (Not for their meat, for their fur. Rabbits seem to be the only thing the Chinese don’t eat). In Hola, in fact, everybody works. All for one and one for all. Its as simple as that. Coming from the decadent West I found this strange fact slow to sink in. I kept looking for the catch. But for the life of me there didn’t seem to be one. Nothing – except their homes and one tiny patch of cottage garden – belongs to the individual. Everything belongs to all. That is, if you are inclined to be cynical, to the State.

In return for this unremitting labour the commune, through its brigades, takes care of the individual. The pick of the crop is pooled and sold at strictly controlled prices to the householder. The rest goes on to the commune, to the State, or into reserve. And nothing is wasted. The manure from the fish ponds feeds the mulberry trees, the refuse from the mulberry trees feeds the rabbits.

Every worker receives a rate of pay based strictly on the amount of work he puts in. Not a particularly generous rate by Western standards, but enough if you are careful to leave a little over at the end of the month. Workers are paid on a points system according to the amount of work done, the tally being kept by a bookkeeper elected from the team. As Tang put it: “For each, the more he does for the team, the more he earns.”

Tang is more fortunate than most. Fish breeding is seasonal work, so rates of pay here vary according to the time of year. At the height of the season a good worker might earn as much as 20 points for a few weeks; but, as an experienced worker, Tang earns a steady 12 points all the year round. To Tang that means money in the bank. He is saving up for his first bicycle.

The brigade has its own simplified version of the National Health. The commune has its own small hospital and the health-work production team which supplies – at a nominal charge of 1 yuan per person per year – four “barefoot doctors” to each brigade in the field. Tang’s best friend, Whu Ling – a lean, ever-smiling young man with magnificent teeth – happens to be the “barefoot doctor” of the fish team.

He told me proudly how the name was given by Chairman Mao to medical orderlies who served the People’s Liberation Army during the wars of liberation. Yet that is all he is, by Western standards – a medical orderly, with a basic six months’ training in Western and Chinese medicine and a refresher course every year. He is a midwife, too, though most babies these days are born in the commune hospital. And there aren’t so many babies, anyway.

Comrade Wu Ling is also in charge of Family Planning and is apparently making a good job of it. Most women, he tells you proudly, take the Pill conscientiously every day. After two babies they want no more.

And this in China, nation of teeming millions, where only a few years ago distraught Chinese simply killed off the latest baby in order to have one less mouth to feed; and sometimes kept a bucket of water by the bed of childbirth so that the period from delivery to death by drowning need only he a merciful matter of moments.

Another thing that impressed me forcibly is that just as everything produced within a commune, through its brigades, is shared by the commune, so every new experience or discovery is shared by a commune with other communes.

The idea of pearl cultivation – not merely for ornament, but also, when crushed into fine dust, for Chinese medicine – was passed on from a fish breeding team in a neighbouring commune. And twice a year, as the brigade’s expert, Tang travels by rail 2,000 miles to deliver fish fry to communes in the Far North.

The awkward questions

Now I know that communities are no new thing in China, where nothing is new. Eighteen hundred years before Chairman Mao, a popular revolutionary movement called the Yellow Turbans organised into rural communities, whose members ate together, practised public confession, and trained for war.

And I realise that this was very much a “show” brigade. For the land around Wushi on the lower reaches of the Yangtse had always been famous for the richness of its soil; soil, they say around here that only needs manure once a year. In this lushness any organised system of land cultivation on such a wholesale scale as this was almost bound to succeed a thousandfold.

But who really runs it all, and where does the money go? And what do the workers get out of it, except eight hours hard work, a roof over their head, and a full belly every day? Such questions you don’t ask in China. But coming from the West, you’re bound to.

Well, in the Western sense, I suppose the man who really runs the Hola brigade of the Hola People’s Communes is Comrade Liu, chairman of the brigade’s Revolutionary Committee; a handsome slender man with the face and hands of a poet and the longest little fingernails I have ever seen on a man, which I discovered he used for cleaning his ears.

He told me how the brigade balanced its budget. Each team is expected to be self-supporting, pay its costs of production out of gross revenue, and make regular contributions to an accumulation fund. Out of which it could, with brigade’s permission, buy new equipment. In this way the brigade had bought, over the years, 11 tractors, 13 power boats, three water pumps and 14 threshing machines,

All policy decisions within the brigade are decided by vote after a public discussion. Recently Tang’s team discovered that the deeper your fishpond the higher your yield of fish. At a public meeting a decision was taken to re-dig about 100 of the 162 fishponds; a colossal undertaking involving an immense amount of overtime by most of the male population, for no extra pay; but resulting in the general good of the community.

What makes men and women work like this; with no reward but the good of all? It seemed embarrassing, in this year of materialistic disgrace 1973, to put such a question.

No beggars

Comrade Liu smiled and told me a story which was really the story of Hola over 20 years. Before Liberation, he said, 16 households here were beggars, 119 households relied on long-term hired labourers, 120 households depended on moneylenders, 45 households had to sell their land and houses to live.

“In the old days 80 per cent of this land was owned by poor landlords,” he said. “And famines were constant.

“Look at us today. Last year we built about 150 houses, 542 families out of 986 have savings in the bank. Many own bicycles and sewing machines, where before we owned nothing.

“But don’t ask me for statistics. Go into the streets and look for yourself. You will see no beggars. We are healthy, we are well fed. Above all, we are happy. Because, through the leadership of Chairman Mao and our own efforts, we have found self-respect.”

Against such argument there is no answer.

Jerry F 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player