RESPONSE TO COMMENTS ON PART 17

There were some great comments on Part 17 so thanks to every-one for that. There are two in particular and one question I’d like to pick out and reproduce.

I nearly missed Tachybaptus contribution because he didn’t post it until some time after publication but it complements my own work so neatly here it is again.

“A late comment on the Oseberg ship and its replica. You can see clearly in the picture of the replica that it’s quite broad and almost flat-bottomed. Probably it never took to the open sea. It was a vessel for rivers and fjords, but its type didn’t matter when it was pressed into service as a burial ship.

The second ship in the Oslo museum is the Gokstad ship. Narrower and deeper, it was a real seagoing vessel. In 1893 a replica was built, named Viking.

It was made as exactly as possible but the builders lacked the great skill with hand tools of the old builders and the ship turned out considerably heavier than the original. But it was absolutely seaworthy and was sailed across the Atlantic to be an exhibit in the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago. It still exists, in Geneva, Illinois, at Good Templar Park. For years the ship was left exposed to the elements and decayed badly, but it has now been restored and housed in a glazed enclosure and is in a viewable condition again.

I have a book, A.W. Brøgger and Haakon Shetelig, The Viking Ships, which describes the transatlantic voyage of the Viking. The crew were delighted with the seaworthiness of the ship, whose flexibility allowed it to slide gently over the high waves of the North Atlantic. There was particular praise for the steering oar, which was much easier to turn than a stern rudder but just as effective. Obviously the single square sail didn’t allow sailing at all close to the wind, but it worked well enough and got them across without problems.”

More images and information can be found on these websites – Friends of the Viking Ship and Viking Skip, and godutchbabyblogspot.

The second comment was from Chimpmonkey who described how he and sailors under his command on a Commercial Ship repelled boarders during a pirate attack in Ecuador. That rang bells with me because I once sailed to Bahia de Caraquez, up the coast a bit from Guyaquil and wondered when he was there. His comment also relates to something I have in mind as a theme for a Piracy embedment in a later article but I won’t say anything more about that here. Here’s Chipmonk’s comment again:

“Talking of Piracy. I have actually given the order to stand by to repel borders while my ship was attacked in Ecuador while in the Guayaquil river. They have had a go in a couple of other locations worldwide as well but this time they managed to get on board.

Fortunately AB’s from Liverpool come in very handy on such odd occasions and after a short kerfuffle on deck ( for want of a better word but football hooliganism seems to have its benefits) a couple of the borders were despatched over the side into the water, while the others decided on discretion being the better part of valour and Disembarked pronto.

They are rarely like that and come armed on most occasions and ready to do serious injury if necessary so the idea is to prevent the approach if possible or certainly boarding.

The Swedish ship ahead of us however was less fortunate and lost its mooring ropes. New ones were brought out in the morning, at great cost, which I very much suspect were the original ones they lost.”

The third comment I’d like to make some remarks about was by McBoatface who asked:

“…..how much moolah do you need to set aside to keep a boat on the water?”

Martin Lomax gave one answer – “You might as well burn ten pound notes on a barbecue”. That was a warmer variant of an expression common in the mid-1990s – “Sailing is like standing under a cold shower tearing up ten pound notes”.

In truth, the question doesn’t have a simple answer because it all depends on the type of sailing being contemplated and the type of boat one is thinking about choosing.

I certainly don’t want to mislead McBoatface or anyone else who looks at my photos and wonders whether they could afford to enjoy the same sort of sailing that I did. Its almost like the old saying that “You can’t afford a Rolls Royce if you need to ask how much it costs to run”. At an earlier stage of my life I certainly couldn’t have afforded either to buy Alchemi or to pay for the Insurance, Mooring Fees, Maintenance and return air fares to distant countries that I did in practice incur.

When I decided to go for a new lifestyle I was nearly 60 years old and at the end of a nearly 40-year professional career. I was not taking it up as a hobby despite the categorisation that sometimes appears at the head of my articles. I didn’t keep accurate accounts and have forgotten many details but I guess my average annual spend was something like 5% – 10 % of the initial purchase price – less in the early years and maybe a bit more later when I had to replace the engine and arrange more comprehensive maintenance.

That sort of sailing can be enjoyed much more cheaply and I met several younger people who had adopted the lifestyle as one of freedom and adventure because they chose not to take the “marry early-have kids-service a mortgage” route through life. They typically bought a second hand yacht, did virtually all the maintenance needed, ate a lot of fish they caught themselves, and earned enough cash to keep going from casual work. I remember one such couple had complementary skills – he could restore or maintain anything, she was a good cook, seamstress and freelance journalist. Somewhat more prosperous couples sometimes do something similar but combine their self-sufficiency with having a family by self-educating their children – who develop their parents’ attitudes and independence – its wonderful to see them deploying their minds and bodies using to the full the self-confidence they develop.

It is clear from McBoatface’s further remarks his circumstances are completely different from mine, and probably from the ones I have just described. I’ll continue by making some observations on what I take to be his motivation – namely to have fun on the water at modest cost and as a recreational activity during relatively short sessions. His reference to a trailer-sailer and Porthmadog are the clues that guide me.

One of my colleagues and friends spent many holidays at Porthmadog having fun with his young family sailing a “Topper”. He always spoke very highly of the water, the beach and the sailing conditions. A craft that can be carried on top of a vehicle is about as low-cost as one can go and provides a good deal of flexibility about venue from day-to-day.

A larger craft creates a need to think about the type of sailing one has interest, time and money to indulge in. Those looking for speed and excitement might choose a catamaran such as a Dart or a Hobie. Others looking for a more traditional style of small boat might prefer a Wayfarer or similar.

There are so many variables I cannot give more specific advice and encourage McBoatface to do lots of reading and thinking before he decides what would be best for him.

Alchemi’s 1997 Cruise – Oslo to Bergen – 1

The schedule I had drawn up when planning leg 4 of Alchemi’s 1997 cruise allowed 3 weeks to get from Oslo to Bergen and that’s what it took between 12 July and 4 August.

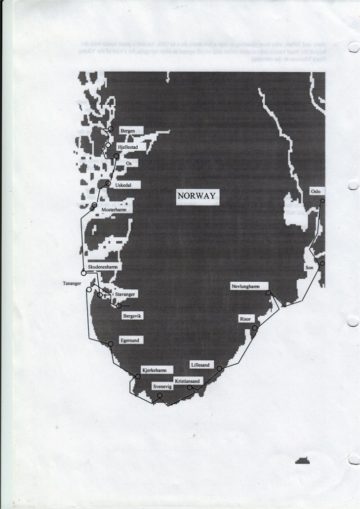

However, to keep each article to a reasonable length and embed within it more remarks about piracy this one will cover just the section along Norway’s south coast. Here is the usual map showing the overall plan for this leg.

Bergen’s latitude is a little over 60o N and others have told me since that I should have taken the opportunity to go right up to the Lofoten Islands just outside Narvik at approximately 68oN. Cruise Ships often do because its north of the present position of the arctic circle at about 66o N. Being able to say you’ve been in the Arctic where the sun never sets in summer, and never rises in winter does have a special appeal, especially in summertime if you can get enough sleep.

I say the present position of the arctic circle because the earth’s position relative to the sun varies from year-to-year and that causes the arctic circle to move around within a range of about 2.5 degrees. The main drivers for the changes are believed to be gravitational effects associated with the moon and the other planets that are all moving about in space but return to the same relative positions from time-to-time..

Three main types of change have been identified and each type has its own cycle over time

Wobble of the axis over about 26,000 years

Change of angle between the axis and the orbital plane over about 41,000 years

Change in length of the orbital axis over about 100,000 years.

There is a fourth type too which is a wobble of the plane in which the earth orbits. All these are matters that fascinate astronomers and climatologists but are unlikely to be of much immediate interest to humans whose current life expectancy at birth ranges from about 49 years in Swaziland to 83 years in Japan.

I also expect GP readers will be more interested to learn the summer in 1997 was a particularly fine one and that people say you’ve only really seen the fjords if you’ve been north of Bergen

I may have missed a rare opportunity by not doing that but I don’t really regret it because Bergen was an ambitious enough target for me at the time, it was compatible with my overall objective of getting back to Falmouth before winter, and it was at the northern limit of my insured cruising area.

In addition to myself there were two others on board as we left Oslo – one young lady from the Cruising Association, who had wavered a little in early July but turned up trumps, and my companion on leg 2 who came again for another three weeks.

SON, NEVLUNGHAVN AND RISOR

We made our way the first day to a small port called Son on the eastern shore of Oslo Fjord a little north of Horten where I had stayed on the way in. Here we moored to the harbour wall and were soon visited by a sailing Swede and his son who came aboard for an inspection and conversation about boats.

The son returned the following morning, complete with girl friend, and gave us a schedule of radio frequencies on which local weather forecasts were broadcast and copies of extracts from their Swedish Pilot Book to the south coast of Norway. We reciprocated with information about UK waters and particularly about tidal navigation with which they were unfamiliar because there’s a much lower range on their home coast.

For lack of wind we had to motor most of the next day, all the way to Nevlunghavn, as recommended by our Swedish visitors, and anchored overnight outside the small and crowded harbour.

There was a good wind the following day and brilliant sunshine as we found our way through some pretty intricate passages between the mainland and some offshore islands until arriving just outside the town of Risor. My journal had this to say about getting into the harbour –

Our entry was mostly straightforward but there were one or two tense moments when going past a lighthouse on a rock 20 feet to starboard with an equally close rock awash to port.

Moored in the harbour we found ourselves next to a friendly Norwegian who told us he had stopped off at Falmouth when sailing back from the USA via the Azores. He said we’d chosen the busiest time of the whole year to visit because these were the three weeks when most Norwegians take their summer holiday and a lot of them do so on the sunny south coast.

THE SKAREGARD AND LILLESAND

This stretch of coast between Risor and Lillesand is similar in some rspects to the Bohusland archipelago in Sweden. It has a chain of offshore islands and a continuous but not straight channel between them and the mainland. As I write this account now, many years later, I wonder if that is truly so. It could have been just because we’d stuck to the main route through the Bohuslan, or perhaps because I was not very experienced in 1997. The channel is called the Skaregard, and I thought that was very appropriate when pronounced in the English way. The islands themselves seemed a bit lower and smaller than the Swedish ones and to have a lot more vegetation growing on them.

Our navigation wasn’t helped by the installed GPS showing us jumping about all over the place but the hand-held instrument continued to do us proud. We also had an excellent pair of binoculars and I learned on this voyage, here and elsewhere, that eye-balling your surroundings when close to hazards and finding your way in unfamiliar surroundings is a vitally important element in keeping safe – don’t just rely on the GPS and autopilot. (I sometimes wonder if those developing self-driving cars these days really take enough account of the same message).

This was a long and tough day but we finally entered Lillesand harbour and rafted up against a Norwegian yacht with yet another friendly skipper. We had a very late supper and finally got to bed at 01:00 the next day.

In the morning we adjusted our lines to let our friendly neighbour leave and no sooner had we done so than our other friend from Risor came alongside and moored to us – it was a busy time of year. He had moored at Arendal the previous evening but had been kept awake nearly all night by loud pop music and had set off as soon as it was light.

There was a strongish wind blowing straight into the harbour and we decided to replenish stores so the crew went off looking for food whilst I looked for a chart shop. I found it but the owner didn’t have what I was looking for and said come back tomorrow. Lillesand has the reputation of being one of the most attractive towns on the south coast and it is very pretty. Perhaps for this reason it was also very full of holiday makers.

My journal again –

In the afternoon we enjoyed walking around town consuming some of the largest ice-creams imaginable followed by sipping a few beers at the Hotel Norge whilst listening to a local pianist and cellist in the evening sun.

And so to bed, refreshed by a day of rest and looking forward to the morrow.

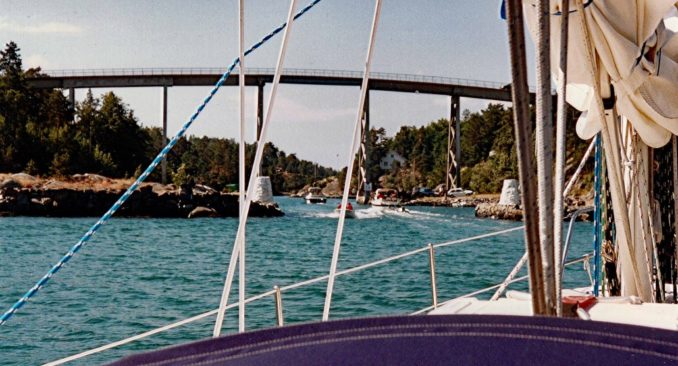

Friday morning was quieter and to my great surprise the book shop had received an overnight delivery of charts including a set of three for the Blindleia passage. This is a waterway about 10 miles long with a least depth of 3.0 m and several places of least width that looked impossible even on a chart at a 20,000:1 scale. Alchemi’s draft was 1.7 m and her width 3.0 m so I could see there wasn’t going to be much margin for error. “Don’t worry” said our Risor friend “although its narrow it will be OK for you, just watch the other boats if you’re in doubt about which way to go”

LILLESAND TO KRISTIANSAND

Sure enough there were scores of boats going in both directions as we approached and entered the Blindleia. The majority were Norwegian motor boats about 20 feet long with canoe sterns. Mixed with these were some real speed merchants, a few gin palaces and several Norwegian and Foreign yachts.

We had no problem route-finding or when watching boats going the same way. But it was a different matter when watching them coming quickly towards us and making for the same central position in the 25 foot wide channel. After some quick stops, some accelerations with bated breath, and some sideways moves made in the fatalistic expectation of a shuddering impact, we were surprised to find we had any time left at all to admire the beautiful scenery.

As we emerged from the channel we realised the wind had been blowing strongly all the time we were in it. The waters outside were really choppy as waves from the open sea met reflections of their predecessors coming in all directions from the many nearby islets. Those conditions didn’t last long though because it wasn’t far to Kristiansand.

When we got there we found all berths were currently occupied except the outer ones from which we were told all boats moored thereto had to leave in the middle of the previous night because swell entering the harbour had made them untenable. Fortunately, a solitary boat left not long after and we darted like a greyhound let off the leash into the vacant space, laying a stern anchor as though we’d been doing it all our lives. The entire passage was only 17 miles long and took just five hours. But it felt two-three times longer because of the need to concentrate so hard.

The next day was my birthday and I celebrated by ‘phoning my mother who was then six years older than I am now. She was still missing my father of course – who wouldn’t after 65 years of marriage or thereabouts. She was keeping well and my sons had both been visiting regularly to keep her company, do odd jobs, and make sure she was OK. I felt the same sort of emptiness after only 37 years of marriage but was keeping the demons at bay by this new life-style requiring deployment of all my physical and mental faculties very nearly all the time.

I reflected on these things the other day as I enjoyed a rare call from my 21 year-old granddaughter – I hoped my mother felt the same pleasure at my call to her from Kristiansand as I did at my granddaughter’s call to me from Milford, where she’d been counting bats – so the wheel of life keeps turning, like the seemingly endless cycles of the solar system.

PIRACY – 3

The most important part of this mini-essay in a sailing and piratical context is the section about events in the 12th and 15th centuries but for readers to understand those I need to ask them to gallop through the preceding few hundred years.

PERIOD BEFORE THE ARABS

More or less at the same time the Vikings were ravaging the coasts and rivers of the British Isles and France, and using the eastern rivers of Europe to do the same in what we now call Russia, Hungary, Ukraine, Romania and Bulgaria, so the Iberian Peninsula suffered from depredations by the people in nearby North Africa.

That region was called Mauritania by the Romans so some think the inhabitants, mostly Berbers (Graeco/Roman word for barbarians), must have been called Maurs at first with “generations of mumbling” (as my latin master used to say) turning that word into Moors and the name of the country many of them lived in to Morocco.

The Romans were succeeded by the VisiGoths in Iberia and as Byzantine Romans in North Africa. The latter survived until the 600s and 700s AD when they were overwhelmed by the Arabs.

The Moors, were independently raiding and attacking the Visigoths whilst the Arabs were busy with the Byzantines but after they’d dealt with them the Arabs carried on westwards and conquered the Moors as well.

ARAB DOMINANCE AND START OF THEIR DECLINE

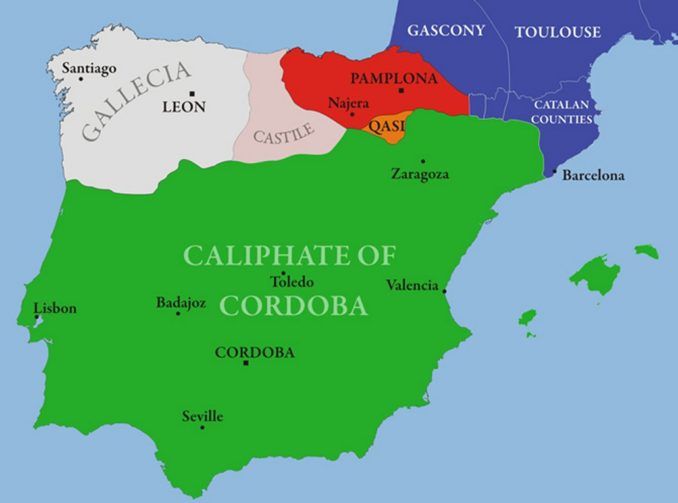

By that stage Arabs were in a numerical minority so they started conscripting Moors into armies led by Arabs but containing relatively few of their own fighters. Initially it was these armies that were used by the Arabs in a full scale invasion of Iberia. So, its highly debatable whether this was a muslim invasion or just a land-grab in the early days. A true distinction may never be ascertained but it is known that after penetrating into southern France and being repulsed by Charles Martel at the Battle of Tours the Arabs consolidated their gains in a land they called Al-Andalus covering most of the Peninsula except the northern Kingdoms of Leon, Castile and Navarre as shown on this map.

In January 929 the Emir of Cordoba proclaimed himself Caliph and that had symbolic significance because in the Muslim world there is supposed to be only one Caliph who is intended to be recognised by all muslims as Mohammad’s successor and Supreme Leader of Islam in all matters – Political, Military, Judicial and Religious. That has only happened intermittently because of rivalries for the succession between members of different clans overlaid by differences of method by which the supreme leader is selected (Sunni – election by tribal leaders, and Shia – leading descendant in Mohammad’s blood line).

In this case the self-declared Caliph of Cordoba (who was a Sunni from the Ummayad clan) was contending with two other guys – who were the Caliph of Baghdad (another Sunni but from the Abbasid clan) and the Caliph of Tunis (a Shia from the Fatimid clan)

The Ummayads in Cordoba had a good run and it was under their rule that Spain’s great advances in art, science and architecture were made including the Great Mosque of Cordoba, the Alhambra in Granada and many other famous buildings. On the religious front it is notable that the Ummayads in Spain were quite tolerant of other faiths and there were many Christian and Jewish communities in several cities – including Caceres which I visited not long ago where the Jewish quarter is still standing.

It wasn’t to last though, and the Northern Christian Kingdoms started to push back in a process known as the Reconquista. That proceeded at a different pace in different parts of the peninsula and was accelerated when the Arabs started disagreeing with one another around 1050 and Al-Andalus broke up into a number of fragmented mini-states.

During this period all sorts of alliances were formed amongst the Christians including one between the King of Leon and Henry, a brother of the Duke of Burgundy. As reward for his services the King made Henry the Count of Portugal that was a province of Leon at the time. They remained allies and Portugal became an Independent Kingdom in 1139 recognised as such by its neighbours in 1143.

THE SIEGE OF LISBON AND ITS CONSEQUENCES

A small army of English Knights stopped off in Portugal during their voyage to Palestine to fight in the second crusade. They did so in order to help King Henry, who was now called Afonso I, to capture the city from the Moors during the siege of Lisbon in 1147 – but their motives weren’t entirely altruistic.

An agreement was struck before the fighting began – If they won, Afonso would have sovereignty over the land, buildings and people, but in exchange the Crusaders could keep any loot they found and any ransom money for release of captured prisoners with wealthy relatives.

That sounds to me just like the Somali demands for release of the Chandlers. Should we be proud of one that happened some 860 years ago but condemn the other because it was so recent? Would this be a good subject for that radio programme – what was it called – The Moral Maze?

The siege was a success with the result that some of the Crusaders decided to settle there and goodwill was created between “the powers that be” in both England and Portugal.

The English were in the country again a couple of hundred years later with King John I of Portugal supporting John of Gaunt in a claim he made on the Crown of Castille. Gaunt didn’t win his claim but settled instead for a bundle of cash to go away (about 400 years earlier the English paid Danegeld to the Vikings and called them pirates – another topic for the Moral Maze?)

Gaunt maintained his friendship with King John (perhaps they shared the cash) and the two of them agreed the Treaty of Windsor in 1386 that still survives as the oldest International Treaty in the World still in force.

The Treaty was consolidated by the marriage of John of Gaunt’s daughter Isabella to King John and that very nearly takes me to the next period of piracy I’d like to mention, though the events I’ve just described seem indistinguishable from piracy to me.

Perhaps robbery with violence is Piracy if its being done to “us”, but “Maintaining Order” if we’re doing it to them – whoever us and them happen to be.

PIRACY IN THE ALGARVE

NO! NO! DON’T CANCEL YOUR HOLIDAY. I’m not talking about piracy in 2021, or even in 1998 and 1999 when I twice sailed down the Portuguese coast.

I’m going back to the early 1400’s when the Algarve was a far cry from today’s tourist destination with its overdeveloped towns, golf courses and crowds of North Europeans suffering from sunburn.

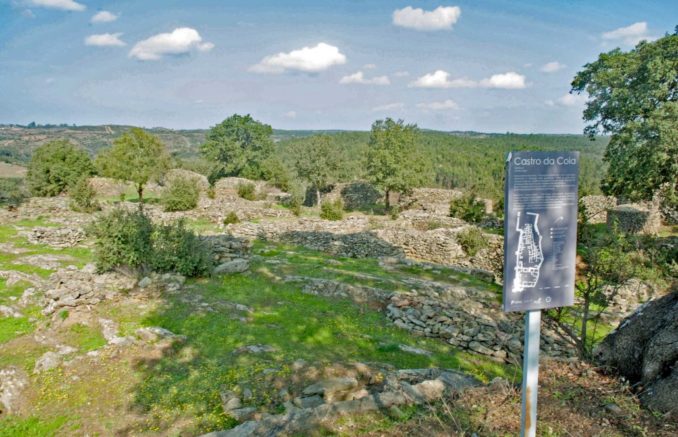

At the time, the Moors had been completely expelled from Portugal (though not from southern Spain) and it was a poor land with scattered villages and hamlets mostly occupied by subsistence farmers and fishermen. It was an ideal target for Moorish Pirates from Morocco who frequently raided all along Portugal’s southern coast and seized anything of value that could be carried away – including people who could be sold in the slave markets of North Africa. Anything that couldn’t be moved was burned or razed to the ground.

The raids understandably upset the local population and those who survived petitioned their rulers for protection.

King John/Afonso and Isabella had four sons. The youngest was Prince Henry who had been appointed Governor of the Algarve so he became responsible for protecting the coastal communities from the pirates. In 1415, when he was 21, he persuaded his father to mount an expedition to capture the pirate’s home port of Ceuta that still exists today as a Spanish enclave in Morocco.

The campaign succeeded but didn’t stop the pirate raids because they just went round the corner and set up shop again in Tangiers. Furthermore, they always seemed to be able to sail away without being caught. Henry asked his shipwrights to design and build some boats that could sail as well as the ones used by the pirates.

They came up with a design known as a Caravel that had Lateen sails. They were a bit bigger than the work boat in Madagascar whose photograph was included in Part 4 of this series and had two masts and sails rather than just the one of the workboat. Readers of these articles will recognise these were much better at going to windward than the square-rigged ones Henry’s ships had been using hitherto.

In fact they were so good that they soon put a stop to the piracy and Henry told his sailors to go farther afield. He also established a school of navigation at Sagres, near Cape St Vincent, the most south-western cape in Portugal and Europe. By these means Henry became known as “The Navigator” though he didn’t go on any voyages himself. But his captains and their successors went far and wide.

THE AGE OF DISCOVERY

Thus began the period now called the Age of Discovery which was pioneered by the Portuguese who discovered routes down the west coast of Africa and on to Mozambique, India, South East Asia and the Far East. They also explored the Islands of the North Atlantic and, in competition with the Spanish, the east coasts of both South and North America. The Spanish had noticed Portuguese success and hired a couple of Italians to do the same for them. They were called Christopher Columbus and Amerigo Vespucci whose exploits are well known. Well Columbus’s are, but Vespucci didn’t do so badly because America was named after him.

In 1494, and as a result of Colombus’s first voyage over the previous two years the Spanish thought they alone should have colonial rights in the lands Christopher had discovered. They appealed to the Pope to adjudicate and he said all land west of 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands should belong to Spain and land to the east to Portugal.

The Treaty of Tordesillas was agreed between Spain and Portugal to give effect to this ruling and neither thought it necessary to consult anyone else about this arrangement, least of all those living in the lands they now claimed.

Some say the Portuguese pulled a fast one when they insisted on the 370 leagues because they’d already discovered the easternmost part of Brazil but hadn’t told anyone else of its existence. That makes a good story but as there was no agreed definition of how many degrees longitude were covered by 370 leagues it may be apocryphal.

A more common explanation is that Brazil was first discovered and claimed for Portugal by Pedro Cabral in 1500. Vespucci was also active on the east and northern coasts of South America at this time and worked alternately for both the Spanish and the Portuguese. Much farther north Fernandes Lavrador, another Portuguese explorer, was busy doing the same around the coast of continental North America. The English were in the region a bit earlier and had already discovered and named the island of Newfoundland, but Fernandes did so well on the mainland it was named Labrador in his honour.

The ships these later explorers used were a slightly larger successor to Henry the Navigators caravels, had three masts instead of two and were called carracks. They still used a lateen rigged mainsail but flew square rigged ones on the foremasts. That combination gave them the flexibility to change sail plan so they could move well downwind by prioritising use of the foresails whilst still being pretty nifty when going upwind because of the power and balance of the lateen mainsail.

I seem to have strayed a bit from discussing piracy but that’s what I started with – and so did a lot of what we know about the world today.

To be continued …………….

© Ancient Mariner 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file