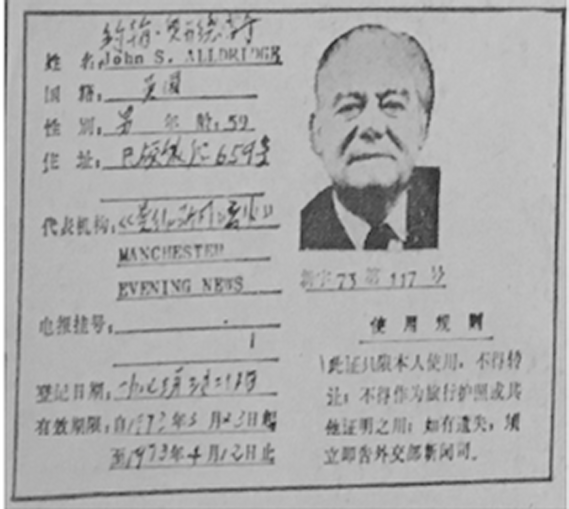

My uncle was a staff reporter for the Manchester Evening News from the late 1940s until his death in 1973. The following is from a series of articles in which he describes his extensive visit to China in 1973 and provides a fascinating insight into what life was like in China 50 years ago. It is reproduced with kind permission of the Manchester Evening News.

My uncle was a staff reporter for the Manchester Evening News from the late 1940s until his death in 1973. The following is from a series of articles in which he describes his extensive visit to China in 1973 and provides a fascinating insight into what life was like in China 50 years ago. It is reproduced with kind permission of the Manchester Evening News.

Hangchow is a very ancient city – “the greatest that may be found in all the world” was how Marco Polo described it when he was spying out the secrets of the silk trade around 1320. It is from the land of the Willow Pattern and its city of pleasure gardens and pagodas that John Alldridge reports.

Spring and port wine

Hangchow, the capital of Chungen Province and the ancient capital of the Southern Sung Emperors before the great Khan came and saw and conquered, is more than 1,300 miles south-west of Pekin. I flew there, smoothly and dead on time, in a Soviet-built, but Chinese piloted Ilyushin jet-prop in two hours and a half.

When I arrived it was raining. This was the first rain I had seen in China and the first my Pekin friends had seen for three months. After the parched dusty North, the smell of that rain and the sight of green things growing everywhere was like coming into a new world.

Spring had come early to Hangchow. And with it had come the peach blossom and the first green shoots of spring wheat. We drove from the airport through avenues of pine and lacy willow. The ditches were full and fat pigs wallowed happily with the ducks at cottage doors.

This was a warmer, more relaxed China. The girls seemed prettier and the old folk fatter, and life seemed to move at a slower, less urgent pace. Or maybe it was just that spring has come a little early this year. Hangchow, despite everything, has been rich and fat and prosperous since before recorded time.

For Hangchow, or Quainsaw, as Marco Polo knew it, is very old. A decade before Canute, a Sung Emperor here in Hangchow commissioned an encyclopaedia running into 1,000 volumes. “The greatest city that may be found in all the world” Marco Polo called it. When he was here, spying out the secrets of the silk trade, around 1320, it had a population of over a million: and that at a time when London’s barely reached 100,000. Its streets were well paved with brick and stone and the inhabitants got fresh water through terra cotta conduits from six main reservoirs and it had its own water-borne sewage disposal system.

It was a city of pleasure gardens and pagodas, of leisurely excursions in lake barges. A city of many inns where rice wine was served in silver cups, and where Marco sampled for the first time the strange delicacy he was later to introduce into Europe – ice cream.

It has changed quite a lot since then. Although it still provides an all-the-year-round supply of fresh vegetables, it also makes huge quantities of chemical fertiliser. Its population has just topped 3m. And since it has always been a fat, tantalising prize to invaders, it suffered a great deal from the Japanese and the wars of liberation.

I dined – and drank a great deal of the famous red wine of the district which tastes uncommonly like old crusted port – with Madame Chang, the editor of Hangchow’s biggest daily newspaper. Here is a girl who certainly came up the hard way. At 18 during the Japanese war she was serving as political instructor with a guerilla company. After Liberation in 1949 she joined the women’s regional committee, got a job as a reporter, and now, 23 years on, she edits a paper with a daily circulation of 400,000 and commands a staff of 150, of whom 130 are women. She has also managed somehow to raise a family of five.

But the old immense charm of this ancient city remains. Pleasure seekers still take leisurely excursions on the West Lake, although most of them now are factory workers enjoying a well-earned convalescence, and the lovely lakeside villas built in traditional Chinese style which remind you so much of Geneva are more likely to be summer homes for groups of Young Pioneers down from Shanghai for a week.

I took a trip myself on that lovely West Lake. They had given me a room in a luxury hotel with a view of the lake to send Conrad Hilton into hysterics. The stairs run right down to the landing stage and from there we sailed away straight into a Chinese fairy tale.

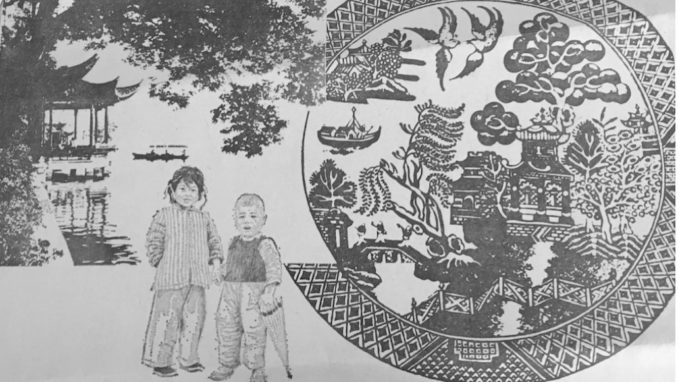

For, of course, this is the Land of the Willow Pattern Plate. There they all are – the tiny artificial islands with names which sound like the distant tinkling of windbells: Orioles Singing in the Willows, Autumn Moon on the Calm Lake, Three Towers Reflecting the Moon.

There are the tiny bridges, each like a miniature crescent moon. There on each island is its tiny pavilion, with its improbable curling roof. And, festooning it all, dozens and dozens of graceful, fluttering weeping willows. All that is necessary to complete the old story are the runaway lovers and the old money-bags of a father. But then the tiny, incredibly beautiful parks, where the cherry blossom and the first magnolia are just in bloom, are full of lovers. Though they all wear baggy blue boiler suits now. And the father? Well, the People’s Liberation Army has long since taken care of him. As for the turtle doves – you remember, the willow pattern plate has two of them hanging in the sky? There are thousands of them here and they never stop singing all day long.

After my boat ride I strolled through the little parks and smiled at pretty young gardeners who were weeding with tiny hoes and hid their faces under their big straw hats when I tried to photograph them. All except one, a bold-eyed minx who sat up and waited for her pic, and smiled and smiled as if all Hollywood is just around the corner.

I fed enormous goldfish that thrashed and splashed for my breadcrumbs like miniature whales. I clapped hands with dozens of eight-year-old Pioneers who sang their party piece and then burst into giggles. And all the time nobody tried to sell me anything. And nobody told me not to walk on the grass. Not for quite a long time, I think, have I been so utterly and completely contented.

Up in the hills around Hangchow grows the coarse, fragrant green tea which I have taught myself to brew up every morning with the hot water in the vacuum flask kindly provided by the management (you can’t go for 10 minutes in China without everything stopping for tea: served in man-sized mugs with sensible lids).

It is also the centre of the richest silk producing district in China. Silk worms have fed on those mulberry trees since long before young Marco Polo came spying out trade secrets. For a couple of hundred years – until crafty Europeans smuggled the silk worms out in bamboo poles down the Silk Road, by way of Bokhara and Samarkand, to Venice – China had a world monopoly.

And they are still making silk in Hangchow. In a garden factory, surrounded by oleanders and magnolias, I found craftsmen, young and old, tirelessly working on designs passed down from father to son through countless generations. I found one man, well on in his fifties, patiently marking out with Indian ink a design for clouds and mountains that had already taken him two months and would lake him two more months before he had finished it.

But the age-old craft has now been mechanised. On elderly looms, painstakingly repaired piece by piece, 1,000 workers were working three shifts – eight hours to a shift. A 40-hour week for which the average wage is 60 yuan. Or just over £3 a week. And the deputy director – another woman – told me she only gets a pound or two more than that. But they have their lodgings provided and their rent taken care of. And as much food as they can eat. And every six months a free holiday. Meanwhile they can get on with the job that most of them have been trained to do, almost from the cradle. Here a man can spend three months painting a mountain, and meanwhile if he has any problems – why, Chairman Mao will look after that.

I watched a roll of rich cream brocade come off a loom. Then a roll of turquoise blue; then an ever richer sheen of mandarin yellow. In each case the design was the same: improbable islands, and bridges, and curly-roofed houses, and weeping-willow trees. But then I told you, didn’t I, that this was the Land of the Willow Plate?

Jerry F 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file