In the now forgotten days when human beings were still allowed to show their faces and set foot out of the house rather than get fat on furlough, soon to become Universal Basic Income followed by euthanasia, I went to Thailand for a short Spring holiday. Thailand is a country I love, which I shall unfortunately never visit again since I proudly wear the yellow star of the unvaccinated; but that is another matter.

I had been in Bangkok but a handful of days when, one clear morning, I walked past a small travel agency and caught sight of an advertisement for an excursion to Kanchanaburi in the window. Being an ignoramus, I had never heard of Kanchanaburi although I had seen Bridge On The River Kwai many years before. The photographs stirred my natural curiosity, I went in and signed up for the excursion.

The following morning, we left Bangkok at six o’clock sharp on an air-conditioned minibus. The Thai are not known for being tardy, which is one of the many things I love about them. We reached Kanchanaburi shortly before nine and were taken by our tour guide, a soft-spoken Thai gentleman, to the train station. The first part of the excursion consisted in taking the original 1940s train and travel over the famous (or infamous, whichever way you want to put it) Bridge over the River Kwai all the way to the Burmese border.

We had barely waited five minutes on the platform before our train arrived and I was suddenly taken back to my father’s stories about the war. The benches and floor were made of wood and, unlike our safety-obsessed times, little attention had been paid to security. A bell rang, no one cared whether the doors were tightly shut, the train set off into the unknown, and that was that.

The train runs slowly, about twenty miles per hour, which allows passengers to take in the view, and, let me tell you, there is a lot to see. For some reason, I had always imagined the River Kwai as nothing more than a small tributary, if not a brook, and the bridge as a rickety wooden, if not straw, structure. My, was I in for a shock! The River Kwai is gigantic, bordered on both sides by lush vegetation. Our guide explained that in those days it swarmed with mosquitoes and as a result many British prisoners of war died overnight from malaria. No wonder it is called “Death Railway.”

I cannot describe the bridge itself other than as the work of titans. I did not yet suffer from fear of heights in those days which was lucky for the bridge is built very high up over the river. The most impressive chunk is that which runs along the mountain. Rather than build a tunnel, the POWs were made to dig into the rock face so as to form a narrow ledge on which the tracks were laid. Perhaps, some of the military historians here may be able to explain why the Japanese had this done rather than a tunnel. The guide told us that many POWs died building that bit, by far the most perilous of all.

After an hour or so we reached the border with that super friendly country, Burma, (I hate the name Myanmar, so unpoetic) and were met by barbed wire and unsmiling border guards holding machine guns, bazookas and other people-friendly implements. I do not read ideograms, but cannot have been far wrong when I guessed that the huge sign planted there read, “No trespassing, or else…” No one on board our historic little train was tempted to do so although the tracks continued way into Burmese territory. The train obediently stopped in front of the barbed wire and travelled in reverse back to Kanchanaburi.

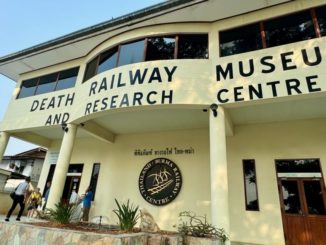

From the station we were taken to the War Museum. It is full of war memorabilia, but what moved me most were the life-size clay figures representing the POWs, emaciated, exhausted, wearing just a loin cloth on account of the heat. On the walls are framed tablets in English which tell of the prisoners’ daily life, the back-breaking work, starvation, beatings, disease… I thought of my father, a veteran on a different theatre of operations, who had not been dead very long then and would have scrutinised every exhibit with the utmost interest. The war had been the most important event in his life.

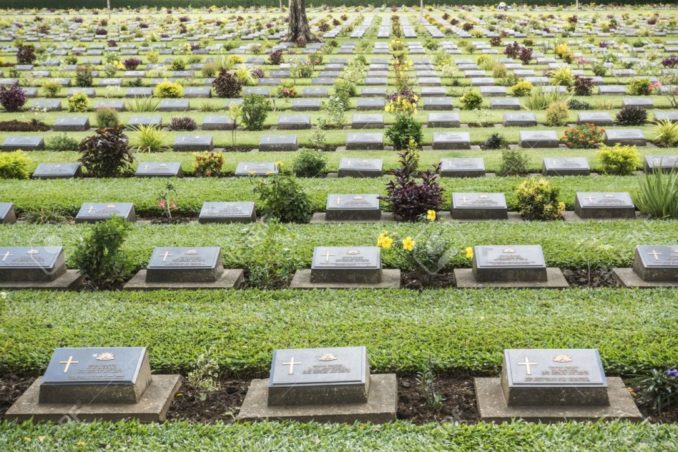

Next to the War Museum lies the War Cemetery, final resting place of almost seven thousand POWs. Just outside the archway leading to the cemetery proper, an elderly Thai lady sitting on a tiny wooden stool gave every visitor a photocopied booklet in English. I took it out of politeness and dropped it distractedly into my handbag. The lady spoke no English, but a slightly younger Thai gentleman standing protectively next to her told us, “It’s her story. Please, read it.”

A sea of small grey headstones extended as far as the eye could see. It was a comfort to notice that the cemetery was lovingly tended by Thai employees, most of them women. Not a single weed was allowed to grow over the graves. I must confess that, apart from the number, what shocked me most was the age of the dead. The majority had been in their early twenties when their life was brutally ended. A few had been even younger. I fell into a sort of daze as I took in the full horror of what had happened. I forgot to mention that as it was not tourist season I was pretty much alone in the cemetery, as I had been in the museum. I was roused from my reverie by four lost-looking youngish men who asked if I could help. They were cousins from England who had come looking for their grandfather’s headstone. Their grandmother longed for a photograph of it. We wandered for a long time before finding it. A captain, he had been just 28 when he died. Suddenly, there was a lot of dust in the air…

Our tiny excursion party was taken to have lunch at one of those lovely patio restaurants that can only be found in Thailand, but it would be a lie to say that I had much appetite. We then boarded a large but flimsy bamboo raft and sailed down the River Kwai. I did not enjoy that part: our group included a fat Canadian yob who kept complaining about the absence of beer; and the river is infested with crocodiles, many of which cheekily came to sun their loathsome silver bellies around our raft.

The excursion concluded with a ride across the jungle on the back of elephants. I had not known until then that elephants are so tall one needs a stepladder to climb on to their back and that a bench fits easily across. I was lucky my mount, if I can call her that, was a placid lady elephant. A young South African man was not so fortunate. His was a teenage male, much given to curiosity, full of mirth and mischief who liked to have things his own way. However hard his gentle Thai driver tried, he could not be nudged into walking straight along the jungle track. There was always a bush or leafy branch, either on the left or right, he needed to have a look or nibble at. He was totally insatiable. Finally, he caught sight of a mud pool and on a whim (he was a very whimsical young creature) decided he fancied a late afternoon shower. His terrified South African rider ended up drenched in muddy water while his teenage mount looked very proud of himself.

By eight o’clock that evening, we were back in Bangkok. It had been a long, emotional, eventful day so I collapsed into bed. The following morning, looking for something (I cannot for the life of me remember what) in my handbag I came across the booklet the elderly Thai lady had given me outside the War Cemetery and decided to read it over coffee. It was about six pages long and told the following story:

The lady had been born and grown up in Kanchanaburi. During the war, when she was 16 years old, a Japanese lorry full of British POWs parked outside the workshop where she was employed. The Japanese driver and guards got out and left the lorry and its cargo in the burning sun while they went somewhere, presumably to get drunk. She got out to have a look and, although she spoke no English and they no Thai, realised that the men were starving. She went home and came back with a platter of rice for which they were grateful.

That same evening, she was arrested by the Japanese and taken to the City Prison. For two weeks, she was subjected to very violent beatings, starved, and finally condemned to death. A couple of nights before her execution, her relatives managed to get her out by breaking her prison cell’s tiny window. A family friend immediately concealed her under sacking at the back of his van and drove her straight to Southern Thailand where he had relatives. She hid with them until the war was over. When the War Museum and Cemetery opened, she decided to write her story down (it was translated into English by a neighbour, she said) and spend the rest of her life sitting outside handing booklets to visitors. She had no interest in recognition, let alone money. All she wanted was that people should know what those days had been like, and nothing would stop her.

I was overcome by regrets. I wished I had read it there and then, and taken the time to talk to that lady. There was so much I wanted to know. But, perhaps it would have been indecent to do so. She gave scant detail of her ordeal. Her style was informative, completely devoid of anger, self-pity, or blame.

Born in or around 1927, she would be 94 now. I have no idea whether she is still alive, a reserved, generous, patient, elderly Thai lady handing her own horror story out of a round vegetable basket to anyone who cared to take it. I hope most, if not all, read it. I made the doll’s house below in her honour. I wish I could have done more.

© text & images Doxie 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player