The preparatory work was completed by early September 1942 and construction began both in Burma and Thailand on the 16th of that month.

Many of the Japanese engineers had attended British universities before heading back to Japan to practise their trade and were already well-versed in designing and building railways through the mountainous terrain of their homeland. Their specification for the Burma Railway was based around the performance of the locomotives and availability of appropriate rolling stock:

- Railway length between Ban Pong and Thanbyuzayat of 415 km (258 miles)

- A gauge of one metre (standard throughout South East Asia)

- Load limit of 15 tons per rail

- Maximum gradient of 1:40

- Minimum bend radius of 200 metres

- Track surface to be 4-5 metres wide

- Fifteen timber railway sleepers every 10 metres

- Stations to be every 10 kilometres

- To be finished by December 1943

The acquisition of materials for the railway did not prove to be any more difficult than obtaining the labour. As part of their war preparations the Japanese had readied almost one hundred locomotives and other rolling stock for shipment to South East Asia. Almost half of these locomotives were landed in Bangkok in January 1942 and were put to use on the railway to Singapore as soon as that line was repaired after the British forces retreated.

The plans for the railway to Burma called for the use of locally available raw materials wherever possible with any shortfall being exported from Japan. During the British retreat from Malaya (now Malaysia) the east coast railway was so badly damaged that the Japanese decided it was better to lift the entire line and transport the rails, bridges and other materials to Thailand for their new route.

Smaller quantities of track materials and rolling stock were taken from the Netherlands East Indies (now Indonesia) and Burma. The most significant of all of the material taken by the Japanese was a bridge dismantled in Java and transported in its entirety to Thailand. This was the bridge that was later to become world famous as the ‘Bridge over the River Kwai”.

Copyright Humbug 2024

The IJA engineer study concluded that for the bridges, 680 timber trestle constructions would be required along the length of the railway and each one was to be built to a common standard as defined in the American Civil Engineers’ Handbook; Just four of these bridges exist today, all located at Tham Krasae (previously called Wang Pho).

No power tools were available to dig the foundations, saw and join timber, remove soil or cut through solid rock. With the initial assistance of some elephants (whose mahouts soon died from disease) everything had to be done by hand, in sweltering conditions and on nothing more than the most basic of survival rations. To speed up construction, the Japanese devised an ingenious way of combining the cement, sand and hardcore required for foundations and bases as a dry mix stored in wooden barrels which were then transported to the construction sites where water was added.

On arrival at Ban Pong or Thanbyuzayat, some groups of workers were fortunate enough to be transported to their work areas. Most, however, were forced to march. In the early stages of construction this was not a major problem since the distance to be marched was relatively short and was made during the dry season. However by early 1943 the situation was changing for the worse. Many of the workers were arriving in an already weakened state after living under Japanese control for more than a year. The distances to march were longer and then in April the rains started. The group of POWs to suffer most from was ‘F’ Force. Now expanded to be 7,000 strong, the British and Australians had to march a total of 185 miles, only by night to avoid the unrelenting heat of the day, carrying all of their personal equipment, medical and camp provisions, Japanese stores plus their own sick comrades. This march lasted seventeen days and passed through camps occupied by Asian workers where cholera had already broken out. The effects of the march, the beatings by the Japanese and malingerers falling prey to local bandits took their toll and many men perished.

Arriving at their worksites, the utterly exhausted workers found dilapidated or unfinished bamboo and nipa palm leaf huts. Others carried worn out tents which were of little use given the ferocity of the rainy season downpours. Often the POWs were not even given time to repair or finish this most basic of accommodation to make it habitable before being forced out to work on their section of road or rail. Whatever the accommodation, tattered tents or leaking nipa huts, the men were packed together like sardines, twenty eight men would share a tent which normally covered eight.

The sleeping platforms added to the distress of all. These were made of split bamboo fixed to bamboo frames. Not only were these platforms a torture to the POW’s emaciated bodies but they also soon became infested with blood-sucking lice and other biting insects. So even the chance to have restful sleep was denied the exhausted labourers. Mosquitoes from above, lice from below. And all night, the demands of dysentery would make already-distressed men stumble and crawl their way to and from the latrines.

Food

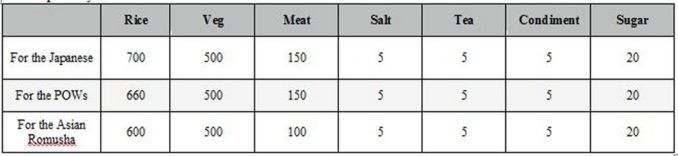

The single factor that had the greatest impact on the health of those who worked on the railway was the food and water, not only the quantity but also its composition and quality. If the following rations (from Japanese sources) had been provided, the Asian labourers may have managed but the POWs would have suffered badly because this diet, of little more than 2000 calories per day, was only half what was required tor Western men performing hard physical work.

Grams per day

In reality the food that did reach many of the camps was often far less than these meagre amounts and was also of poor quality with much of it being pilfered en-route. Rice was the staple food but was often broken grain contaminated with foreign matter such as lime or kerosene (the Allies had attempted to destroy their own rice stocks before their surrender) or dirt, rat droppings or weevils.

Any meat or fish that did reach the camps was in tiny quantities and often rotten and full of maggots, sometimes so bad that it was condemned by the Japanese camp administration and buried only to be recovered later by the prisoners and cooked. Maggots were usually skimmed off the top of the stew before it was served.

Of even greater impact than the small quantity of food was the almost total lack of essential vitamins and minerals which affected the entire slave labour force and significantly raised the risk of death from illnesses such as beriberi (lack of vitamin B1) and pellagra (lack of vitamin B3). Even if they did survive, the POWs suffered from reduced resistance to the numerous tropical diseases which are endemic even today in the area around the railway such as dysentery, tropical ulcers and malaria.

Unknown, A. Mackinnon donated this photo to the Australian War Memorial, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Chances of Survival

The conditions in any camp, and consequential chances of survival were dependent on many factors. These could be natural or man-made and included:

- whether the camp was in a healthy location and condition (provision of latrines)

- whether it had a plentiful, clean water supply

- whether it had access to food supplies

- whether it was close to the railway construction site

- what work the men were forced to perform

- whether the camp had an effective administration, both Japanese and POW

- the ability and experience of any medics

Two ‘H’ Force camps (3,300 men under Malay command) reflect the effect natural conditions had on the death toll:

- Malay Hamlet, situated in a swampy area and drawing its water supply from a muddy, polluted stream, suffered 217 deaths from 745 men in three months

- Tonchan Spring Camp was established close to a large natural spring and only 29 of its 600 inmates died

Two ‘F’ Force camps reflect the effect of man-made conditions:

- Shimo Songkurai, populated by prisoners who were initially in reasonable physical condition and who carried out normal railway and road construction tasks, had strong medical and camp leadership. This camp suffered 151 deaths from its 1600 men

- The nearby camp of Songkurai had a similar number of men but who were drawn predominantly from the hospitals of Changi. These men were forced to build a bridge across a large, fast flowing stream. The leadership of this camp was ineffective and uncaring of the welfare of the men. 600 men died in the camp itself and another 600 died after transfer to a hospital camp

© SWMBO & Humbug Slocombe 2024