Part One of the Postcard from Romania covered our arrival in the beautiful city of Cluj-Napoca, in May of 2018. In writing it, I tried to dispel just a little of the negative impression many people hold of Romania. I also provided a whistle-stop tour of the early history of Transylvania (whose name translates to ‘the land beyond the forest’ or ‘on the other side of the woods’).

Despite the pervasive influence of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Transylvania is not all vampires, werewolves and gothic horror. It is a picturesque area of central and north-western Romania, covering around 39,000 square miles, and is made up of sixteen counties (judeţ). One of these counties, Județul Cluj, incorporates the Apuseni Mountains, Someș Plateau and the Transylvanian Plain. In spite of the terms ‘plateau’ and ‘plain’, it is largely hilly and rugged terrain, a county known for its abundant and wide-ranging natural resources, and a diverse flora and fauna.

It is also a place where it’s possible to take a step back in time. Visiting Sic, a small village only a short distance from the city of Cluj, is an experience we regrettably missed out on. The old houses still have the traditional blue walls and shaggy thatched roofs. The people here are primarily ethnic Hungarians (thought to be direct descendants of the nomadic pastoralist invaders, the Hun), who call their village Szék. They are renowned for their distinctive styles of vocal and instrumental music and dance (the táncház).

Most of the time, the population still go about their everyday lives dressed in their traditional, richly embroidered folk costumes, as they have for centuries. The men sport felt ‘pork-pie’ or straw ‘bucket’-style hats, and deep blue waistcoats with brass buttons. The women are resplendent in crisply starched, embroidered white blouses, polka-dotted red flowing skirts, and neatly tied headscarves. A far remove indeed from the modern, bustling city of Cluj, the county seat.

© Urbán Tamás, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

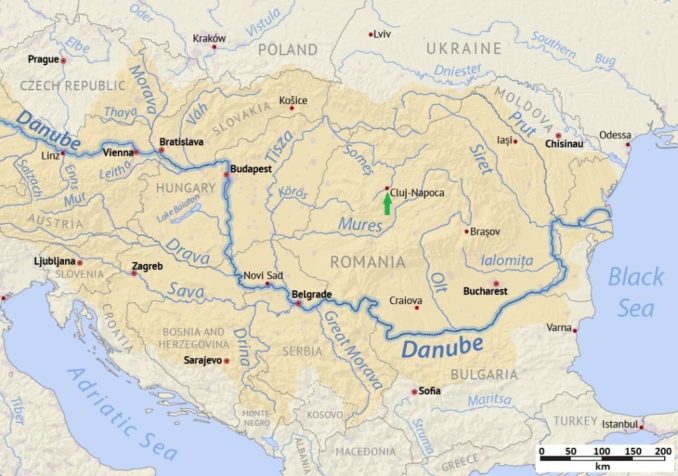

Cluj stands astride the banks of the Someșul Mic (Little Someş) river. As with so many things European, the river systems of Romania are incredibly complex, with tributary upon tributary, meandering from county to county, region to region, sometimes country to country across numerous borders until they reach the sea. The Someșul Mic rises in the Apuseni Mountains (part of the Western Romanian Carpathians) and runs through the Transylvanian Plateau, where it combines with the Someșul Mare (Great Someş) river to form the Someș. From there, the waters zig-zag northwest to join the River Tisza (one of the main rivers of Central and Eastern Europe) before feeding into the Danube on its journey to the Black Sea.

© Shannon1, under GNU Free Documentation License

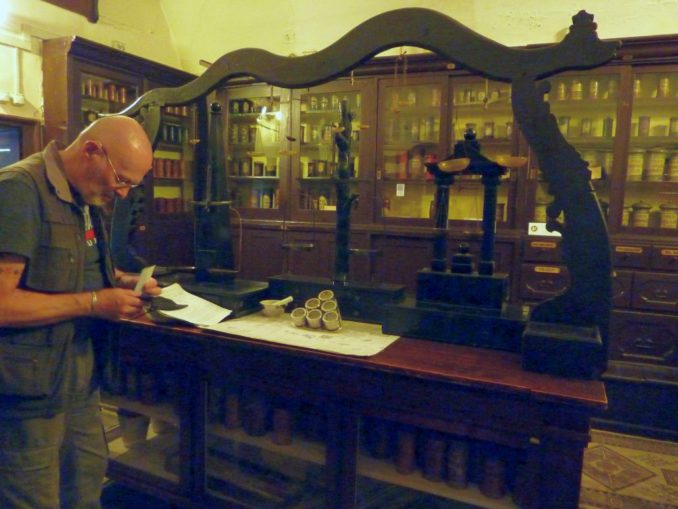

But the fascination of the rivers aside, our plan for today was a visit to the Hintz or Mauksch-Hintz House. An apothecary’s sanctum sanctorum for nearly 450 years (apart from an unfortunate spell when, in 1949, the pharmacy was nationalized and turned into a bakery and pastry shop under communist rule). For the last sixty years, Hintz House has been home to Cluj’s Museum of Pharmacy (part of the National History Museum of Transylvania).

The classicist façade of the building which you see as you approach, dates to around 1820. This belies the interior which holds a few surprises, as the ground-floor and the basement were built in the late 15th to early 16th centuries, during the Renaissance.

The Historical Collection of Pharmacy encompasses a wealth of fascinating artifacts, roughly 3,000 pieces from a time when the line between medicine and alchemy was still indistinct. The collection ranges from porcelain and glass vessels, presses, old balances, laboratory instruments, and old pharmacy furniture, to medicines, recipes, documentation, and mediaeval official stamps. It is said to be one of the oldest, and most intriguing collections in the whole of Eastern Europe, a claim I’m quite prepared to believe.

The first surprise is the entrance fee: 6 lei each and an additional 25 lei for a photography pass. Coming to the princely sum of slightly less than £7.50, it’s a steal, as there is so much to see and marvel over.

Standing on the corner of Strada Regele Ferdinand (King Ferdinand Street) and the main square, Piața Unirii, the building housed the first public pharmacy to be established in Cluj. This was a ‘city pharmacy’, operated by the local administration, and it opened in 1573. In 1727, the pharmacy ceased to be city owned and it was instead sold to a private pharmacist, Alexander Schwartz, who ran the business successfully for several decades. Upon Alexander’s death, his widow asked nephew, Tóbiás Mauksch (who, coincidentally, was born in the year Alexander bought the pharmacy), to take over, then in December 1752 she sold him the business.

The Mauksch family, for the most part pharmacists, came from the Tatra Mountains in northern Slovakia. Tóbiás, whose father was a furrier, was orphaned aged 12 so was sent to Cluj to complete his apprenticeship in his cousin’s apothecary. An ambitious young man, he learned the basics of his trade there, then transferred to pharmacies in Ludwigsburg and Stuttgart to complete his training. He returned to Cluj in 1752 to buy Schwartz’s pharmacy while still in his mid-twenties. At that time, outside of his pharmacy, the entire city’s patient care was delivered by only three doctors and six surgeons. Tóbiás was an outstanding, precise pharmacist. An extraordinary man and a shrewd businessman, he was elected city senator and parliamentary ambassador, and he was the custodian of the local Lutheran parish. He married twice and sired 18 children.

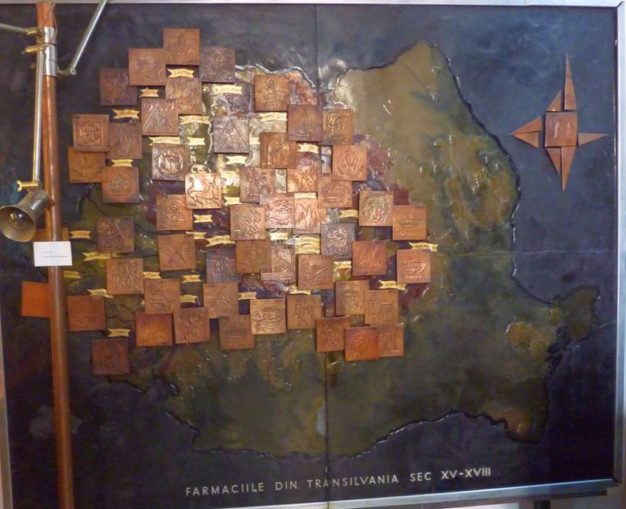

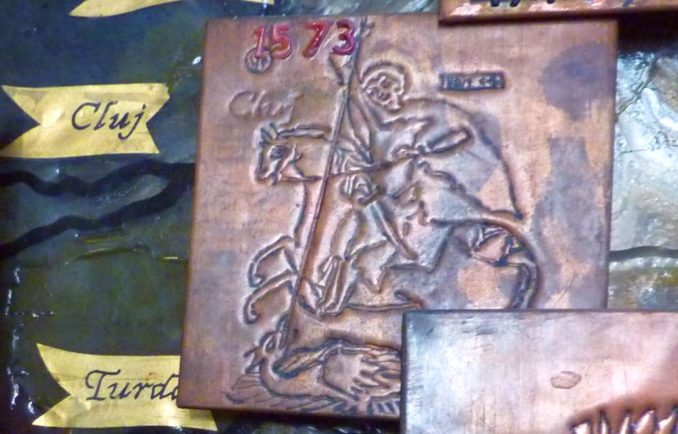

Stepping into the museum’s entrance from the street, the first thing you see is a large copper wall panel. A map of Transylvania shows the registered pharmacies of the 15th to 18th centuries, with small copper plaques displaying the symbol of each pharmacy. At that time, the Hintz House pharmacy was known as La Sfântu Gheorghe (St. George’s Pharmacy).

© SharpieType301 2018

© SharpieType301 2018

The museum is quite small, comprising just four ground floor rooms and a basement. The rooms are a delight, and the objects displayed in them are extraordinary. The original purpose of each room, with one exception, has been preserved as it would have been in the 1750s.

Small, is not a reason to pass a museum by, as Orhan Pamuk points out in his Modest Manifesto for Museums (developed in parallel with his ‘Museum of Innocence’, which opened in 2012 in Beyoğlu, Istanbul):

“It is imperative that museums become smaller, more individualistic, and cheaper. This is the only way that they will ever tell stories on a human scale. Big museums with their wide doors call upon us to forget our humanity and embrace the state and its human masses. This is why millions outside the Western world are afraid of going to museums.

Monumental buildings that dominate neighbourhoods and entire cities do not bring out our humanity; on the contrary, they quash it. Instead, we need modest museums that honour the neighbourhoods and streets and the homes and shops nearby, and turn them into elements of their exhibitions.”

The first room you encounter as you step upwards out of the entrance hall is the Materials Room where medicinal ingredients were stored. Lined with painted wooden cabinets, row upon row of wooden apothecary drawers, and glass-fronted shelving packed with hundreds of original vessels in which the materials were kept. Here too is a collection of delicate balances on which drugs and medicines were weighed.

© SharpieType301 2018

A small interactive display stands on the central table, inviting you to identify six plant-based ingredients (herbs and spices) by their distinctive smell and appearance. There’s a traditional, undecorated, workmanlike terracotta stove in the corner of this room. These stoves go back to the potters’ guilds in 14th and 15th century Transylvania, and the manually pressed and painted terracotta tiles (cahle) used on the stoves’ stone or clay walls, help to maintain the heat.

© SharpieType301 2018

The finest room is the Oficina (the shop floor), the public space in which the pharmacy sold medicines to local citizens. Here, the terracotta tiled stove is much more ornate, with hand-moulded glazed tiles in a rich, dark red, as befits the prosperous impression the showroom offers. Tóbiás Mauksch knew the marketing value of projecting a successful image. The walls are lined with shelf upon shelf of beautifully labelled Majolica and glass pharmacy jars of all shapes and sizes.

© SharpieType301 2018

Unique in Transylvania is the opulent Baroque, vaulted ceiling. Custom-made for Tóbiás, and completed in 1766, this lavish original feature represents a considerable investment. Designed to impress even his most affluent customers, it epitomises his keen business sense. One fresco, the earliest, dating to 1752, tells the history of the pharmacy in the Hungarian language. Then there are four frescos at cardinal points of the room, framed by oval medallions. These depict pharmaceutical and healing symbols: the tree of life framed by two serpents of Aesculapius (Greco-Roman god of medicine), and a crane atop a leafy branch, holding a pebble in its claws (symbolising observation and vigilance).

There is an intriguing assortment of odds and ends in this room. Busts, painted panels, pestles and mortars, portable balances, dockets and orders, weights and measures, and all kinds of interesting bits and bobs.

© SharpieType301 2018

This small mediaeval apothecary was important for centuries, with the city’s populace visiting for advice about their ailments and to buy drugs, candles, cosmetics, and balms. However, in amongst the more commonplace stock were also more exotic, and expensive products, and the display in the centre of the room holds some of the more unusual ingredients used by apothecaries. Beaver butt exudate, anyone?

Castoreum:

a highly aromatic (and not in a good way), yellow-brown butter-like substance, secreted from membranous sacs between the anus and external genitals of beavers. Soluble in alcohol, it is prepared for use as a tincture. In the 12th century, the Benedictines drank powdered beaver ‘testicles’ in wine to reduce a fever (the dried castoreum gland is easily mistaken for testes). In pharmacies such as this, castoreum would be used to treat earache, toothache, colic, and gout. It was thought to induce or prevent sleep, and ‘strengthen’ the brain. It was also used to cure headaches. This, at least, makes sense as it contains salicylic acid, the main ingredient in aspirin.

Lizard dust:

a ‘drug’ concocted from the pulverized bones of Asian lizards (labelled as Stincus marinus) this is actually Scincus scincus, the common or sandfish skink. This was sold as an aphrodisiac for young women, to treat sexual impotence, as a powerful diuretic and for leprosy!

Hydrargyrum praecipitatum viridis:

an alarming mixture of mercury and copper sulphate, dissolved in nitric acid, that precipitates to a solid substance, and is then dried. This was used as a potent antiseptic to treat infected wounds, but probably wasn’t for the faint-hearted.

Bezoar stones:

not actually stones, but a mineral concretion which forms around undigested organic matter (often hair or fibrous material), typically in ruminants. There were many legends about the stones’ origins, and they were handled like precious gems. Their exotic name derives from the Persian word padzahr (pad – expel, zahr – poison), a clue to their use. Also useful as emetics, antipyretics, consumed to counter pestilence, to prolong life, or simply as a medicine of last resort, the stones were greatly prized. In 1768, under Tóbiás’ ownership of the pharmacy, Abbot Francois–Xavier de Feller, a Jesuit theology professor with a celebrated aptitude for mathematics and the physical sciences, wrote that:

“In Cluj I saw a beautiful bezoar brought from America, weighing one libra and two ounces. Here are some [bezoars] that weigh up to eight libras…”

Who knows, he may have seen this splendid specimen (8 libra = c. 2.6kg) in Tóbiás’ pharmacy.

Extractum Taraxaci:

the concentrated the juice of the dandelion plant, Taraxacum officinale L., produced by pressing the whole plant and evaporating the extracted juice. This was recommended, in different doses, for treating intestinal obstructions, as a laxative and diuretic (who else remembers mum telling you not to eat dandelions as they’ll make you wee?).

Hyraceum:

an aromatic raw material used in antique perfumery, formed from the fossilised urine of the Cape Hyrax or Dassie (South African mammals resembling large guinea pigs). The urine is not passed as a fluid but as a jelly-like substance which then hardens. Traditionally, the peoples of Africa and the Middle East used Hyraceum to treat epilepsy, kidney problems, convulsions and feminine hormonal disorders.

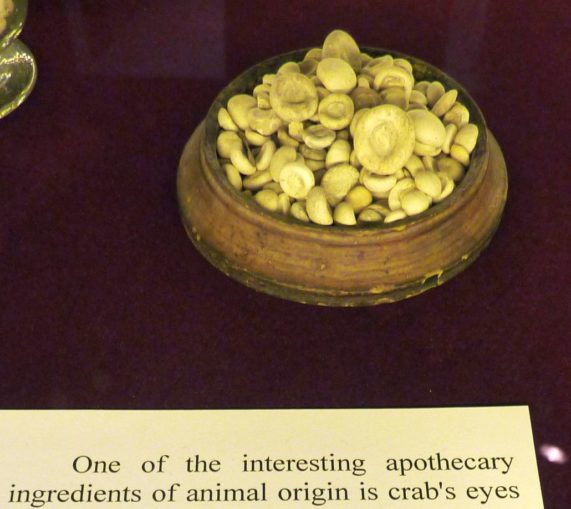

Crab’s Eyes (Oculi Cancrorum):

the calcareous concretions found in the stomachs of river crabs, is a natural source of calcium carbonate used to sooth colic, ulcers, or an acidic stomach. Also used to treat hysteria, as a remedy for pleurisy, asthma, and to cleanse the teeth.

© SharpieType301 2018

Theriac (also known as Theriaca Veneta, or Venice Treacle):

a panacea to prevent any form of illness, to ward off such illnesses as asthma, colic, dropsy, inflammation, and even the Black Death, and as an antidote to poisons or poisonous bites. This peculiar and costly concoction, which took an inordinate length of time to prepare, contained as many as 70 ingredients.

It was based on a substance called mithridaticum, a potion developed by Mithridates VI of Pontus and Armenia Minor (around 120–63 BC) as a ‘universal antidote’ to counter all types of poison, including the venom from scorpions, vipers, and sea-slugs. Mithridaticum contained nearly 50 ingredients, including walnuts, figs, rue, skink, duck blood and… a pinch of salt!

Theriac was first mentioned in Galens’ books De Antidotis I, De Antidotis II, and De Theriaca ad Pisonem, and in addition to the complicated concoction which was mithridaticum, contained a further 15-20 ingredients, the most important of which were viper’s flesh, opium, honey, wine, and cinnamon. Before use, the final product was supposed to mature for years!

© SharpieType301 2018

There was another precious, apparently miraculous, medicine sold at the pharmacy, dispensed in tiny amounts costing more than its weight in gold. Popular between at least the 12th and the 17th centuries, possibly into the 18th century and beyond, its use was widespread. It was seen as a ‘go to’ drug in many European countries… for those who could afford it. What could this remarkable substance be?

Pulvis Mumiae (Mumia vera aegyptiaca):

considered an all-powerful panacea for a broad spectrum of diseases. A medicinal tonic, a painkiller and anti-inflammatory, a revitaliser, a blood thinner, a cough suppressant, effective for ‘nervous complaints’, dysentery and beneficial for bumps, bruises and contusions as a means to promote would healing.

In truth, the origins of this marvellous medication are rather grisly. It was produced from the body parts of embalmed Egyptian mummies, ground to a fine powder!

© Ryan Somma, licensed under CC BY 2.0

Indeed, one of our own rulers, King Charles II, believed that mummy dust held the secret to greatness. He applied it to his person to absorb the powers of the Pharaohs and was also known to sip his personal tincture made from alcohol and ground human skull (conceivably from mummies), known as ‘The King’s Drops’, to increase his health and stamina.

As bizarre and barbaric as it may sound, there may be a grain of truth in the vaunted healing properties of this macabre ‘drug’. The embalming materials used in Ancient Egypt were a complex mixture of natural compounds such as sugar gum, beeswax, fats, coniferous resins, pistachia resin (possibly Chios turpentine) and bitumen (asphalt or tar). Many of these are made up of terpenes (mono-, sesqui-, di- and triterpenes) which are now proven to possess antiseptic, antiviral, antifungal, and/or antibacterial properties.

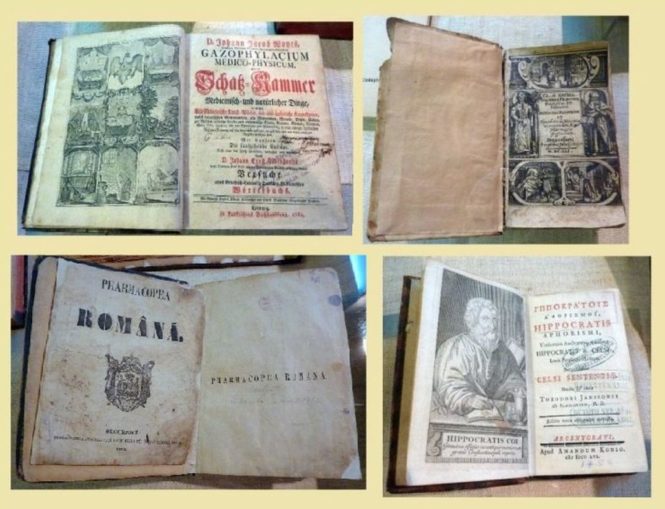

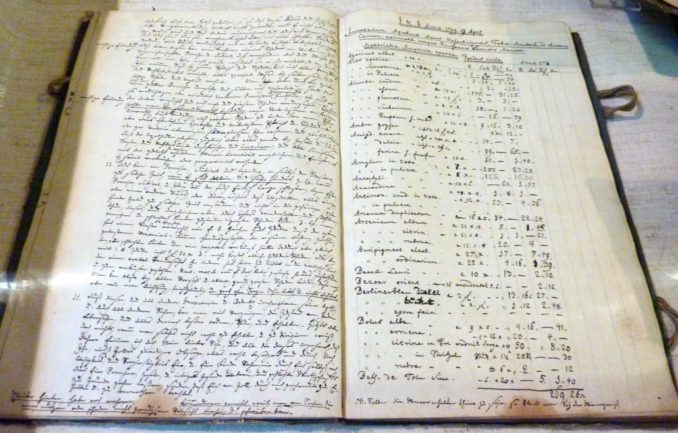

The next of the museum’s rooms to explore is the Book Room, where pharmacists’ ledgers and pharmacology reference books are exhibited. One of the pharmacy’s ledgers, open to the page concerning 9th April 1799, is fascinating, listing materials, amounts and prices, written in beautifully meticulous copperplate script.

© SharpieType301 2018

© SharpieType301 2018

This room holds two manuscripts written by Tóbiás Mauksch, one of which is his 1793 ‘Instruktio’. This gives advice to his young son, Johann Martin (for whom he had bought a pharmacy in Târgu Mureș), on how he should run his business. Tóbiás explained all of the most important aspects of pharmacy management, describing general duties, the procurement of raw materials, the production, storage and sale of drugs, and the selection and remuneration of staff. He particularly emphasised ensuring quality, across every area of pharmaceutical activity.

‘Instruktio’ included a section on ethics and social competency, to cover relationships with patients, doctors, and the authorities. He advised his son to be careful with his assistants and servants, that they didn’t waste time at revelries or cause embarrassments that would dishonour the pharmacy’s reputation. Also, around Christmastime, Tóbiás advised his son that a pharmacist should pay a short visit to the local doctors, bearing a gift to ensure that they’ll send him customers. At the time, lemons were seen as an exotic luxury, so the pharmacist should offer:

“Six lemons for the more experienced doctors, and three for those who had less experience.”

Of more personal and paternal concern, the manuscript gave his son advice on how to become the successful and contented head of a family. Unfortunately, Johann died, so couldn’t take over the Târgu Mureș pharmacy, nor use the valuable advice lovingly written for him by his father.

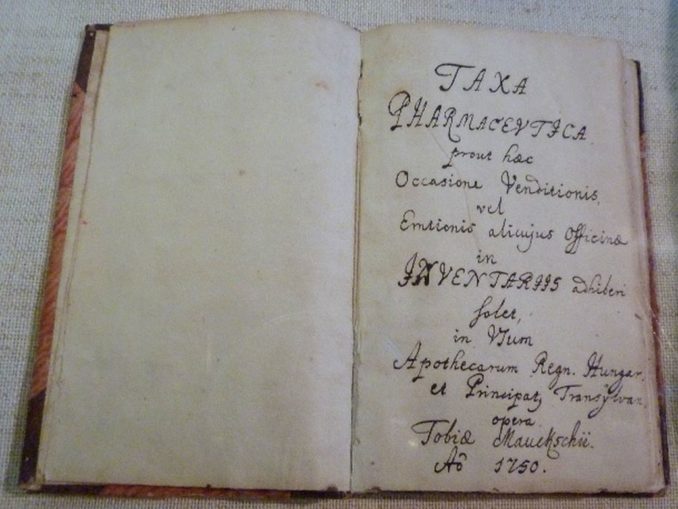

Tóbiás’ other manuscript was his Taxa Pharmaceutica. Written in 1750, this is an inventory which listed the pharmaceutical products that he used or produced, together with his prescription formulae and tariffs. The drugs dispensed at pharmacies were either prescriptions prepared according to a physician’s direction, or a concoction of an apothecary’s own devising.

This beautiful, carefully handwritten tome would have dipped into medical botany (study of the medicinal value of plants, following the first herbalist and ‘father of pharmacology’, Dioscorides), pharmacognosy (the study of plants or other natural sources as a possible source of drugs), and pharmacodynamics (what a drug does to the body). All of these topics eventually developed into an independent discipline, pharmacology, which has its roots, like modern medicine, at least in part, in the Middle Ages.

© SharpieType301 2018

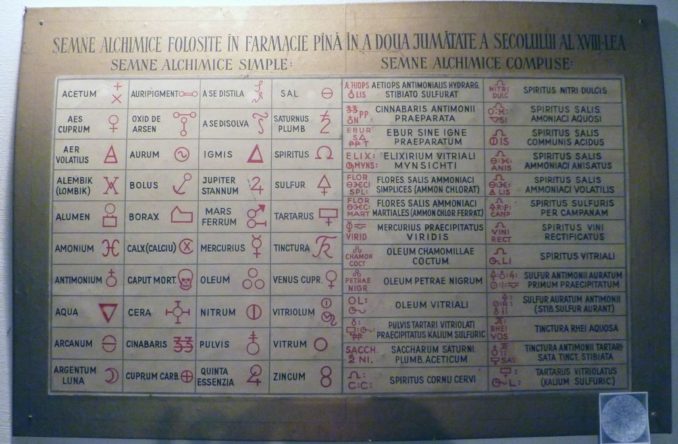

The walls of the Book Room are decorated with prints of apothecary scenes, perhaps taken from the pages of a book, and a large chart displaying a table of arcane apothecaries’ symbols.

© SharpieType301 2018

© SharpieType301 2018

Once again, the shelves here are lined with captivating artefacts, including medical instruments of the kind used by the barber-surgeons (don’t ask!). There are gorgeous blue glass bottles, with heavy, facetted ground-glass stoppers, and clear ‘laboratory’ glass jars of minerals: calcium phosphate, copper sulphate, ferric oxide, zinc oxide, and more.

© SharpieType301 2018

Also on the shelves are the ingredients of, the recipe for, and the extremely pretty hand-painted glass bottles that would have contained happiness-in-a-bottle, the Elixir of Love. This recipe contained red wine mixed with rose petals and various spices such as cinnamon, cloves, cardamom, nutmeg, pepper and orange peel. This would be left to macerate for one day and one night, then filtered through canvas. Even so, the resulting brown concoction (on the right) looks somewhat unappealing!

© SharpieType301 2018

However, unlike other Mediaeval recipes of this nature, this one actually appears quite pleasant. Love potions from 17th century France included menstrual blood, Spanish flies, and herbs such as verbena, while those from England suggest mixing periwinkle with leeks and earthworms to “strengthen love between a man and his wife”. Personally, I’d rather go with the modern version, which combines white rum, Amaretto, chocolate liqueur, and heavy cream. There you have an Elixir of Love cocktail I’d at least try! Perhaps LP could put it on the menu at The Gate Hangs High?

One of the objects on display caught my attention but wasn’t really explained by the museum. Beautiful and practical, it was obviously a travelling medical case of some sort, but it wasn’t until we were back home in the UK, did I find out more about it. It is an apothecary chest once owned by Transylvanian noblewoman Tereza Keményi. The varied contents would have been used in an emergency when a doctor or pharmacist could not be found. The contents, though costly, would simply have been the ‘essentials’.

This portable pharmacy, which she would have taken with her while travelling, has multiple drawers with labels for solid ingredients and twenty-six small glass jars concealed behind sliding panels, to hold either powders (with parchment lids) or liquids (with metal lids). Interestingly, the contents included three different forms of bezoar-related material. One of these, Pulvis Bezoardicus Sennerti (Sennert’s Bezoar Powder), was a mix of oriental bezoar with other highly priced ingredients (such as pearls, red coral, rubies, emeralds, crabs’ eyes, and deer heart).

Sennert’s was believed extremely beneficial, being a remedy for plague, abortion, and the pox, but also of value to those unfortunate souls who had been poisoned. All in all, this skilfully made chest and its contents indicates that its owner was a wealthy woman. Indeed, very well-heeled to afford such an array of expensive ingredients. The chest can be dated to 1787 through a manuscript found in one of the drawers. This is a Specifcatio, a list of products which appears to relate to materials bought to replenish the stock.

© SharpieType301 2018

The final room on the ground floor is the Instrument Room, dedicated to medical equipment. The largest of the rooms, by far, this has a magnificently decorated vaulted ceiling and a huge terracotta tiled stove. Again, this has hand-moulded glazed tiles in Cordovan red. Although the room’s contents are considerably more modern than those in the previous rooms, the collections are still antique. They represent devices used in the hospitals of Cluj from the end of the 19th century until the 1970s.

© SharpieType301 2018

As you step down into the room, the first thing to catch the eye is a leather-covered dentist’s chair, and all kinds of alarming-looking dental cutters and drills (foot-powered, using a treadle). You’d rather hope your dentist was a fit man!

© SharpieType301 2018

There are medical posters, microscopes, sphygmomanometers, electrocardiographs, balances, instruments used in ophthalmology, gynaecology, and physiotherapy.

© SharpieType301 2018

Sterilising autoclaves, Boyle’s-type anaesthesia machines, X-ray machines with more Röntgen tubes of various sizes and shapes that I’d have believed existed. Oh, and books. On the central table, instruction books for apparatus, medical journals, conference publications, and who knows what else. This is an extraordinary collection in every way.

© SharpieType301 2018

Finally tearing ourselves away from this ‘room of wonder’, we make our way back through the Book Room and into the Materials Room, in the corner of which is a small aperture leading down to the basement, down the kookiest and steepest staircase cum ladder we’ve ever encountered. It’s a bit like manoeuvring up into the loft space in my old, terraced house, but going down instead. The wooden treads alternate between each step—one being wide on the left-hand side, the next wide on the right-hand side. They take some concentration to descend, as you have to ensure you use the correct foot for each tread. I’m just grateful that there’s a handrail on both sides!

© SharpieType301 2018

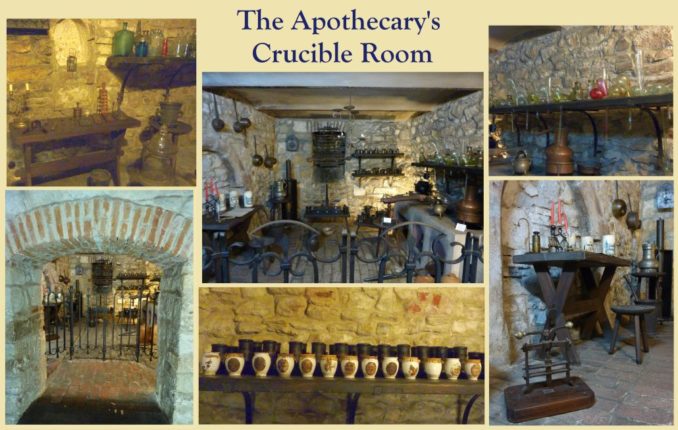

The museum’s basement houses the Crucible Room, a laboratory of sorts in a modest, unseen underground space. Oh, my word, where do I start. Mind your head as you step into each chamber and prepare to say ‘wow!’.

This is the oldest part of the entire building, and it’s like traveling back in time into something resembling an alchemist’s lair. The vaulted stone-built chambers house a brick oven, omnipresent shelves of jars and bottles, balances, tongs and tools, crucibles, presses, mortars and pestles of every size. Tablet-making equipment for producing pills, lozenges and suppositories. Stills and percolators, alembics and retorts, for preparing tinctures and potions.

© SharpieType301 2018

The Crucible Room is where the pharmacy’s lotions and potions, poultices and medicinal recipes were formulated by the head pharmacist and, under his close supervision, prepared by his assistants and apprentices, all amidst considerable secrecy. Deliberately situated in the most isolated part of the building, this allowed the smells and vapours from preparation of medicines to be kept far away from the public areas of the business and ensured the pharmacy’s professional discretion would be maintained.

For a small museum, you might expect a visit to be fairly brief. We were there for hours and still didn’t feel like we’d done it justice. Would we visit again? You bet we would. As we ambled back to where we were staying, we pondered our visit and agreed that we’d be hard pushed to find anywhere better in Cluj. We were to be surprised once again… but that’s a tale for the next episode.

© SharpieType301 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player