I’ve never been myself, but I’m prepared to bet that Stalybridge is rather different today from when my uncle described it for the Manchester Evening News in February, 1947 – Jerry F

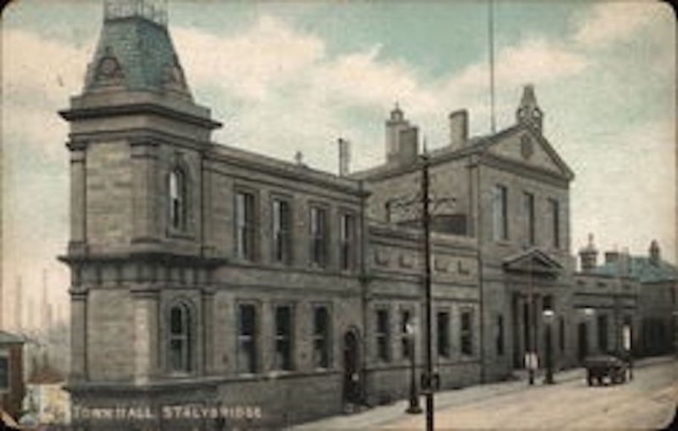

Old Postcard showing Stalybridge Town Hall,

Unknown photographer – Public domain

A blizzard was howling down over the town when I came to Stalybridge.

Banshees were wailing in the Derbyshire hills and invisible machine-gunners, dug in on the Cheshire bank of the Tame, were pouring vicious bursts of frozen tracer into Lancashire. The Town Hall, caked in a rime of snow, was taking the full brunt of the attack.

I should like to know just how that Town Hall came to be built where it is – on the side of a hill, with one side taller than the other, like a man walking with one foot in the gutter. You can get lost for hours in that Town Hall. Enter by the basement in Stamford Street, go downstairs – downstairs, mark you – and you come out on the first floor in Market Street. No matter what corner you turn you seem to end up inevitably outside the Rating Office. You half expert to find Alice and the White Rabbit padding patiently along those corridors.

But a lot of Stalybridge is built like that. The architects of the 1840’s achieved the impossible. They made houses behave like limpets.

For the same reason that you can’t get a gallon of beer out of a pint pot, Stalybridge has never been able to expand properly. Its natural boundaries have been rigidly fixed, but its man-made boundaries are flexible enough. Geographically in Lancashire, for purposes of administration it is a Cheshire borough. It is a parish In the Hundred of Macclesfield. But its 700 Lancashire acres are still in the Diocese of Manchester.

Modern ‘Bridgites would like to clear up that anomaly. They are enthusiastic supporters of a Manchester County Council, which would place Stalybridge conveniently close to the hub. Failing that they are prepared to join forces with Ashton, Dukinfield, and little Glossop, and petition Parliament for a joint county borough.

Never in my life have I seen so many public houses at one time as I saw in Stalybridge. They tell me that within living memory there used to be eighty pubs and clubs in the town. Sam Hill, the Bard of Stalybridge, once wrote a long poem all about the Stalybridge pubs. He found room for 63 of them, with names like “Th’ Frozzen Mop,” the “Friend un’ Pitcher,” “Th’ Owd House o’ Whoam,” “The Floating Light,” and “Th’ Cottage o’ Content.”

When Dr. Johnson talked about “clubbable men” he might have been thinking of Stalybridge. Give the average Bridgite just half an excuse and he’ll form a club. Today Stalybridge, with a population of around 25,000, supports well over 20 clubs, including 15 with political affiliations – seven Conservative, seven Liberal, and one Labour. But there must he many unofficial clubs which meet just for a drink and a song.

For Bridgites by and large are jolly, friendly folk, fond of a good song and a rousing chorus. On April 18, 1808, in a “commodious room belonging to Mr. Samuel Cook, innkeeper,” was held “a Grand Miscellaneous Concert from the works of Handel, Calcott, and others for the benefit of the Music Club.” And a few nights ago 500 townsfolk filled the Town Hall to hear a Pilgrimage of Song.

It is – or was – one of the few towns in England where a local poet can earn a fair living. There was Sam Laycock, for example, Sam started his time as a cloth-looker in a Stalybridge mill. He wrote his first poem on a cop-ticket. But before he died – at Blackpool in 1893 – he had sold over 40,000 copies of his poems.

Stalybridge poets — Laycock, Hill, George Smith, the publican poet, Ben Brierley, Edwin Waugh, and others – were in direct descent from Burns. Their poems,

written in their own homely dialect for the most part, tell of important things in local life – a new set of bells, the coming of the railway to Stalybridge, the opening of the new market hall, potato pie, the town’s bellman,

And it was because of a five shilling bet made in a Stalybridge club that Jack Judge sat down and wrote “Tipperary” in one night. The immortal nonsense was written and composed in the Newmarket Inn, in Corporation Street, on the last day of January 1912, and sung that same evening on the stage of the Grand Theatre just across the street.

The town has a band which is over a century old. It was born in the cellar of “The Golden Fleece” in 1814, when a few youngsters dreamed of buying “2 clarinets, 2 flutes, a bassoon, and a big drum” for a down payment of five shillings and weekly instalments of two shillings each.

Stalybridge is proud of things like that. It is proud of its annual season of pantomime. This month nine church societies and youth groups are giving their own nightly topical versions of “Jack and Jill”, “Babes in the Wood,” and “Humpty Dumpty”. It is proud of its small police force, one of the oldest in England; just as it is proud of its famous unsolved crime, the Gorse Hall murder, committed as long ago as 1909, but still retelled with relish when strangers come to town. It is justly proud of its fine parks and open spaces.

I will add this: there are not many art galleries in the North where you will find a genuine thirteenth-century Buffalmalco hanging, very much at home, beside a very English David Cox. And not many public parks which can boast a bird sanctuary like the one in Cheetham Park, where last year 51 different species of wild bird were counted.

But let Sam Hill have the last word. Nobody was prouder of Stalybridge than was Sam:

“Aw’ve often yerd grand accounts

O’ places up and deawn,

So aw’ thowt ut aw’d say summat

Abeawt my native town.

Yo’ met ha’ seen Killarney’s lakes,

Or climbed owd Snowdon’s ridge;

Bur aw’ll bet yo’ never seed a place

Fur’t equal Stalybridge.”

Text and Image:

The British Newspaper Archive (www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk)

The British Library Board

© Reach PLC

Jerry F 2022