Part Two of the Postcard from Romania saw me waxing rhapsodic about the Museum of Pharmacy at the Mauksch-Hintz House in Cluj. After a fantastic visit, when we spent hours marvelling at the extraordinary collections, we didn’t think it could be bettered and, to be fair, I don’t really think it has been. However, the Transylvanian Museum of Ethnography (Muzeul Etnografic al Transilvaniei) apparently took note of our admiration, and indignantly declared ‘tine-mi berea!’.

The Museum is in two parts: an indoor section in the centre of Cluj, at the Reduta Palace, and an open-air segment at the National Ethnographical Park “Romulus Vuia”, a short way out of the city centre. The outdoor section adjoins the eastern extremity of the Hoia-Baciu forest (which means ‘Shepherd’s forest’), a popular recreational area with numerous hiking trails and biking tracks…by day. But the dense forest is a less inviting place after dark, and is a place enveloped in myths and legends, hiding many secrets.

Our intention was to visit the Romulus Vuia first as it’s quite large and would be a pretty tiring day out, with a lot of walking (not least as we couldn’t figure out which buses went from the town to that area, so Shank’s Pony it was!). Then, we thought, when we were back in the city, we’d follow this with a wander around the indoor collections. However, Mother Nature had other plans. Overnight, the heavens opened, the cloudburst hammering on the Velux windows to keep me awake, and the most incredible thunderstorm with brilliant flashes lighting up our room and the weather gods moving the furniture around in the heavens. Noisy buggers!

The forecast for the next day was unsettled, to say the least, with more thunderstorms anticipated. Meandering around an open-air museum on the top of a hill didn’t sound all that sensible, so we decided to head for the Reduta Palace instead. But before I begin to describe the wonders of this bipartite museum, a little bit of a diversion.

The Hoia-Baciu Forest is a curious area which, if you believe in such phenomena, is one of the world’s hotspots for paranormal occurrences. It has been called the creepiest forest in the world, the world’s most haunted forest, and the Bermuda Triangle of Transylvania. The first chilling legend to emerge from Hoia-Baciu is the one which gave the forest its name. At some time in the dim and distant past, a local shepherd was said to have entered the forest with his flock of 200 sheep, but neither he nor his charges ever returned nor were heard from again. They’d disappeared without a trace. A more recent tale is of five-year-old girl, who have wandered off into the forest (where were mummy and daddy, one wonders) and, as before, disappeared without trace. On this occasion though, some five years later, she is said have wandered back out in a confused state, still dressed in the same clothing, and with no recollection of where she had been or what had happened to her.

Figure 1: Haunted Forest

© Dennis Jarvis, licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

There are reports of orbs, flashing lights moving rapidly through the forest at night, weird fluctuations in the magnetic field, and the failure of electronic devices. Oh yes, also inter-dimensional portals and poltergeist activity, with spirits whose unfortunate souls are eternally trapped within this haunted forest. The forest does appear to be an unsettling place, and countless people claim to be overwhelmed with anxiety and the feeling of being watched as they walk through the trees, some of which grow in odd, inexplicably contorted shapes. Other visitors speak of headaches, nausea, vomiting, and strange rashes. To be fair, I’d be considering leaving those mushrooms well alone! When we were there, an annual Hungarian student bash was in progress—loud rock music, and I daresay some exceedingly dubious practices going on.

Within the forest’s interior, the Poiana Rotunda (a.k.a. ‘The Clearing’ or ‘Dead Zone’) is a vaguely roundish clearing of about half an acre (2,000 square meters) in size where, inexplicably, no trees ever grow. This is the most sinister place in the forest, allegedly, and the source of the paranormal activity. Adding to the many tales of the unexpected centred on this strange forest are UFO sightings. In 1968, Emil Barnea, a 45-year-old ex-military construction technician, photographed a large, round craft hovering over The Clearing. He took several pictures, and noted that the object was of metallic appearance, changed its brightness, and reflected the sunlight as though silver-plated. The machine slowly flew above where he stood in the wood, without any noise, and then accelerated rapidly and flew upwards. Unfortunately, this being the communist era, the poor chap was vilified, with one ‘official’ declaring he was “an ignorant illiterate, undoubtedly an alcoholic, and that his photographs were faked.” However, subsequent analysis by several sources found his photographs to be perfectly normal, without any trace of falsification.

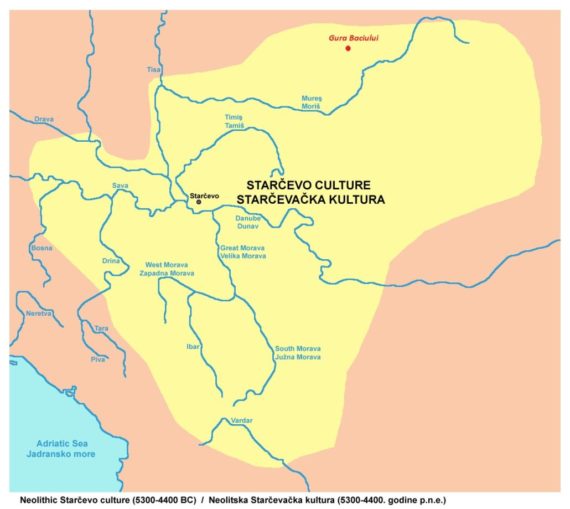

Personally, I lean towards a similar view to one of the local guides, Alex Surducan, who suggests that: “The forest is only haunted if you bring your own ghosts.” Perhaps of more interest to me is that this forest is close to Gura Baciului, the oldest archaeological site in Romania, one which dates to c. 6,500 BC. It would have been interesting to visit the site, which is associated with the Starčevo-Körös-Criș culture. These peoples were some of the earliest farmers in Europe, who expanded northwards from Anatolia in the early Neolithic. Meadows, terraces, hillsides, and even caves were exploited as people settled wherever the landscape and environment was agreeable. Clay bowls and cups, flint tools and large polished stone axes were commonplace. Hunting and fishing was the norm, although evidence has been found suggesting that cattle predominate, but also sheep, goats, and pigs were also domesticated, and the presence of sickles and saddle querns point to cereal cultivation. A fascinating material culture survives, including anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figurines (often made of clay). At this point, small copper items begin to emerge for the first time.

Figure 2: Neolithic Starčevo culture (5300-4400 BC)

PANONIAN, Public domain

Back to the day’s plans, and before reached the Reduta Palace for the indoor collections of the Transylvanian Museum of Ethnography, we took an art appreciation detour. Dodging the showers, we popped into the glorious Baroque edifice which houses the Art Museum of Cluj-Napoca. This is the Bánffy Palace, one of the most imposing buildings in Cluj. Rare and magnificent historic buildings are some of the finest characteristics of Cluj-Napoca, and the city is proudly restoring many of the structures from the Renaissance, Baroque, and Gothic, to their former glories.

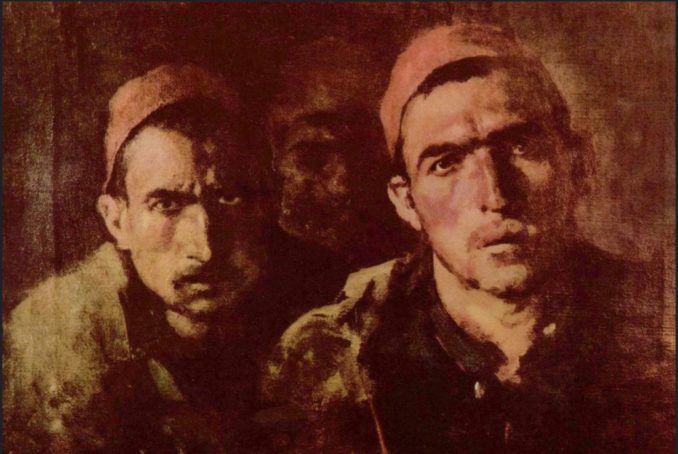

To be honest, though a perfectly pleasant visit, the museum’s collections do not have the commanding presence of the building. That said, one piece really stood out. A small, brooding oil painting by Nicolae Grigorescu, likely painted when he accompanied the Romanian Army as a ‘frontline painter’, a war correspondent of sorts, in the Romanian War of Independence (1877-78). This conflict, also known as the Russo-Turkish War, allowed Romania to gain her independence from the Ottoman Empire, though at a cost of more than 19,000 casualties. The mistrust and despair in the eyes of the defeated and captured subjects contemplating their fate, in Nicolae Grigorescu’s ‘The Turkish Prisoners’, haunts me still.

Figure 3: Turkish Prisoners

Nicolae Grigorescu, Public domain

Finally, evading a few more showers, we found our way to the Museum of Ethnography. Identifying it was not an easy task, as the building was completely obscured by scaffolding, and shrouded in protective sheeting as restoration work is ongoing. This building is rather interesting, as it takes its name from the main hall where balls and concerts were held, this being called ‘Reduta’ (from the French redoute = dance hall). In its heyday, the hall hosted a number of prominent musicians: Johannes Brahms, Franz Liszt, Béla Bartók and George Enescu. Prior to this, in the 18th century, the building was home to the most notable inn in Cluj, the ‘Calul Bălan’ (the White Horse Inn).

As we stepped inside, the first exhibit we saw focused on fishing and hunting, in all its forms. A sizeable jagged-toothed brutal-looking bear trap made me shudder. More common in the past, even today there are thought to be around 6,000 brown bears in Romania, distributed erratically through some 500-odd square miles of mountain ranges. The thought of any animal being caught in one of these vicious, nightmarish contrivances, scared, in pain and despairing, is beyond imagination. On a rather less repugnant note, the nearby display of delicate, hand-knotted fishing nets, woven withy fish traps and a dugout log boat, even with a trident fish spear, is much more appealing.

Figure 4: Traditional fishing methods

© SharpieType301 2018

I hesitated to include the next photo, as the jury is still out on this exhibit, and I can’t quite decide what my feelings about it are. A huntsman’s bag, carefully crafted from a whole badger skin, fur, face and all. Extraordinary, but I think I rather prefer and am more comfortable with the beautifully decorated powder horn in the next cabinet.

Figure 5: The Badger-skin bag

© SharpieType301 2018

Figure 6: Carved powder horn

© SharpieType301 2018

The collections move on to other captivating country-pursuits, such as honey-gathering, cheese-making, and forest foraging (we’re back to those mushrooms!), then on to farming practices of all sorts. The backdrops are often large blown-up black and white photographs of the exhibits (or similar ones) in use. A great idea, which really brings things to life.

Then we get to home crafts, those skills used in the cold, dark winter days when working outside in the bitter Transylvanian winter is best avoided. The crafts on display include leatherwork, and woodcarving. The quality of some of these exhibits is simply stunning.

Figure 7: Leatherwork

© SharpieType301 2018

Figure 8: Woodcarving

© SharpieType301 2018

We press on to slightly more mechanised activity, production of ceramics, metal ore collection, then metal extraction and purification, before we forge ahead to the metalworking and toolmaking. All really interesting, and as is the case across the whole of the museum, as the collections are really extensive with over 50,000 objects, the exhibits can be and have been carefully chosen to give the clearest and most informative impression. This really helps to illustrate the occupations, customs, and everyday life of the Transylvanian rural population.

Textile crafts are next on the agenda, with hemp, linen, and wool, often embellished with beautiful decorative embroidery. Huckaback towels of linen or raw silk canvas caught my eye, their embroidery, often flowers, in a striking rich blue against the plain cloth. There is more use of skins and leather here too, and some great exhibits explaining spinning and weaving, felting, lacework, carpet-making, and other uses of textiles. Combining several of these skills are a series of stunning embroidered waistcoats, based on sheepskin for warmth in the bitter Transylvanian winters, and painstakingly decorated to lift the spirits on dark days – resplendent with the love that went into making them.

Figure 9: Embroidered sheepskin waistcoats

© SharpieType301 2018

Another particularly touching set of exhibits relates to children, with cradles and blankets, toys and rattles, wooden animals, dolls, clothing and more. A sturdy, wooden baby-walker stands out for me here. With the darkened wood and rich patina, I wonder how many generations this saw and helped to stand, then toddle. Gorgeous and, being fashioned for a little one by a doting dad or grandad, so intimate and personal—you can forget those garish plastic monstrosities you’d shell out for at Mothercare and the like.

Figure 10: For the children

© SharpieType301 2018

There is also a tactile exhibition, entitled ‘Touch and Understand – the Tactile Message of the Traditional Peasant Objects’. Encompassing a plethora of the different fields that the museum covers, it was originally designed for visitors with visual impairment. However, it still brings great delight to children of all ages (yes, I’ll confess that I took great pleasure from trying to identify objects by touch alone).

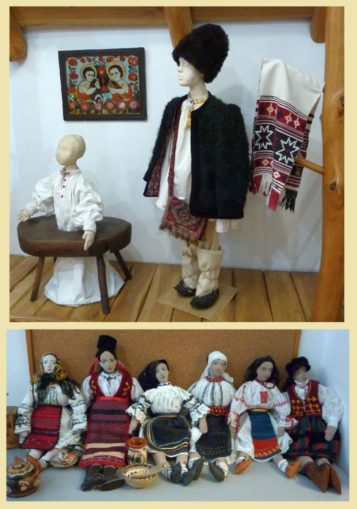

One last gallery before we finished our visit was an absolute must-see. The costumes gallery. Set out cleverly, with mirrors behind, so that you can see the details on the reverse as you delve into the superb collection of regional costumes from across Transylvania, this is a gem. Oh, my word, this really takes the breath away and my sole photo just can’t do it justice at all. Unsurprisingly, I was way too busy leaning in close to these stupendous costumes to explore every tiny stitch and detail. Check out that spectacular peacock feather head-dress.

Figure 11: Costume gallery

© SharpieType301 2018

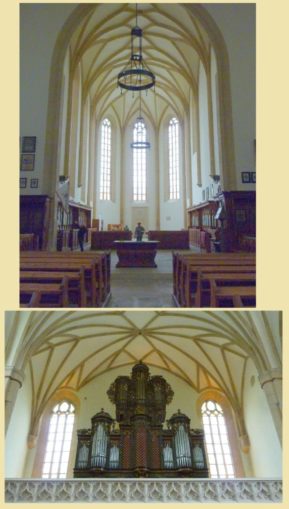

As we said goodbye to Reduta Palace, the rain was starting in earnest. We were keen to make the most of the day, despite the rain, so we headed for the shelter of the Biserica Unitariană din Cluj (the Unitarian Cathedral). A product of the Reformation, the church is in stark contrast to the Orthodox places of worship we had visited. A light, open and airy, calm space, it offers an atmosphere of peace as soon as you walk in through the entrance, passing under the inscription “In Honorem Solius Dei MDCCXCVI” (In honour of the only God, 1796).

Figure 12: Unitarian Cathedral

© SharpieType301 2018

Inside the church is a beautifully executed pulpit, decorated with acanthus leaves, with sculpted moulding, and trompe-l’œil elements of the Rococo. There is also a large boulder. Rather incongruous, one may think, but it is the stone from which Dávid Ferenc (the founder of the Unitarian Church of Transylvania) gave his speech to convert many of the citizens of Cluj to the Unitarian religion. An interesting man who suffered for his faith. Since he disputed the prevailing Catholic view on the Holy Trinity (believing God to be one and indivisible), Ferenc was sentenced to life imprisonment in Déva, where he died in 1579.

Figure 13: The Pulpit

© SharpieType301 2018

Keen to explore every last inch, we headed into the vestry, and there we stumbled across a small exhibition of wooden sculpture by András Kós. We were the only people there, and thoroughly enjoyed taking our time to look closely at his work. If only I could have brought one of his pieces home with me, I would have done. I rather suspect our Reggie would have liked them too.

Figure 14: András Kós sculpture

© SharpieType301 2018

Onwards, and as the rain had finally slackened off we headed for Piata Avram Iancu. A ‘Hero of the Romanian Nation’ who was known as Crăişorul Munţilor (The Prince of the Mountains), Iancu was a Transylvanian Romanian lawyer who headed the Romanian forces, playing an important role in the Austrian Empire Revolutions of 1848–1849. A dignified and complex man, when in 1852 Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria (the longest-reigning ruler of Austria and Hungary) visited the Apuseni Mountains of Transylvania, he expressed a hope that Iancu would agree to meet him. Purportedly, Iancu declined, voicing his famous line “It’s all for naught, a madman and a liar can’t by any means come to understand each other“.

In the square stands his monument, by sculptor Elias Berindei. This behemoth is, unfortunately, hideous so I won’t inflict a photograph on you all. The square itself is a pretty spot, which stretches from the steps of the glorious Catedrala Adormirea Maicii Domnului, the Roman Orthodox Dormition of the Theotokos Cathedral, and the Teatrul Naţional Lucian Blaga, the Neo-baroque Lucian Blaga National Theatre, home of the Romanian Opera.

As we approached this lovely building, small groups of people were arriving, obviously for a performance. We walked up the broad steps to take a quick gander through the doorway and I, rather cheekily, asked if we could step inside to see it in more detail. Not really, we were told, by a smiling lady who ushered us in anyway and told us we could have five minutes. Almost in passing, I asked her what that night’s performance was and (given that it started in ten minutes) whether there were any tickets left. Don Quijote, she replied, and yes there were still a few seats remaining.

Figure 15: Lucian Blaga National Theatre foyer

© SharpieType301 2018

Off we raced to the nearby ticket agent and dashed back again bearing two stalls tickets bought for a small fortune. A ridiculously small fortune, in fact, at the equivalent of £6 each. Amazingly, we found our plushly-upholstered seats were only a few rows from the orchestra pit, giving us a fantastic view. The auditorium is beautiful, gloriously decorated, and with minutes to spare it fills almost to capacity.

Figure 16: A Night at the Opera

© SharpieType301 2018

The orchestra commences, the lights dim, the curtain rises, and Don Quixote, the wandering knight, ambles onto the stage, astride a wonderfully decrepit-looking Rocinante. His ever-faithful squire, Sancho Panza, is by his side. Without a word the pair skilfully portray the Don’s vision and Sancho Panza helps him into his armour. Then the Don falls to the floor into a deep sleep and the curtain behind him rises to reveal… ballerinas!

Ooops, this is not, as I’d had foolishly thought, Don Quijote the opera (it’s an opera house, for Pete’s sake!), but Don Quijote the Ludwig Minkus ballet. I took a sneaky look sideways at Mr S, expecting the worst. He’s not what one might describe as a ballet fan, but he was utterly spellbound. Breathing a sigh of relief, I settle down to revel in two acts of splendid entertainment. The grace and strength of the dancers, the movement, colours, and sheer athleticism combine with the marvellous music and an easily understood story, even without a word being spoken.

The Orchestra, Soloists and Ballet Ensemble of the Romanian National Opera of Cluj-Napoca blew us away with this performance. A comedy, dealing with the search for truth and beauty, even in the most commonplace moments of life. As the performers left the stage for the interval, Mr S turned to me, saying ‘It can’t be over already, can it?’. Thankfully it wasn’t. Act Two was equally entrancing, the male dancers yet more athletic, with great leaps and grand gestures, the dainty female ballerinas gracefully bending and pirouetting, dressed in gorgeous costumes.

Quite possibly the stars of the show for me were the bendy foam Rocinante (a run-down, elderly nag, all sad eyes, sagging head and sticking-out ribs, brilliantly suspended on a steel frame) and Sancho Panza’s trusty mule (again made of steel and foam), huge-headed and sweet-faced. Being on wheels, both could be ‘ridden’ to great comedic effect. The entire ballet was magical and was over far too quickly. I was almost tearful; it was so emotional. What an experience for Mr S’s first ballet. It won’t be his last, although at the ridiculously high price of ballet tickets in the UK it might just well be.

Now around 8:30, it was long past time for a welcome glass of wine and dinner. Thankfully, the rain had stopped, but it was only a short walk to Vărzărie. This restaurant is legendary, a relic of communism, but an absolutely fantastic one, serving delicious classic Romanian food for a modest price. Peasant food, some would call it, but it suited us down to the ground. We started with soup—Ciorbă De Burtă (a heavenly, velvety, tripe soup—don’t knock it ‘til you’ve tried it) and Supă De Fasole Boabe Cu Ciolan Afumat (bean soup with smoked ham hock), then we ordered two plates of sarmales (Romanian stuffed cabbage rolls), one with herbs and cheesy polenta, the other with smoked meat that we didn’t think was ham (it was actually beef and pork), both with a big pile of homemade sauerkraut, a dollop of smetana, and a slab of smoked pork. Delicious.

Figure 17: Varzarie and sarmales

© SharpieType301 2018

We’d chosen a bottle of Feteasca Neagra wine. Meaning ‘Black Maiden’, the ancient grape this wine is produced from is the top the bill grape of Romania and gives a ‘ruby red wine of medium intensity, with a smooth, silky mouthfeel, and rich flavours of plum, cherry, dark chocolate, and some oak’ (it tastes like genuinely nice wine to my uncultured palate). As beautiful as the desserts looked, they were extremely big portions, so we decided against it. A few doors away, along Bulevardul Eroilor, the Gelateria Betty Ice was about to close, so we stopped to pick up a scoop of delicious ice-cream in a takeout tub: pomegranate and pistachio for me, cookies and chocolate for Mr S. We sat on one of the boulevard’s benches under the light of the streetlamps. We ate and drank like royalty that night.

As we started to walk home, we passed a young man quietly playing the guitar and singing. He was playing The Beatles’ ‘Norwegian Wood’ and he was really good, so we stopped a while to listen. Then he began to play Simon & Garfunkel ‘Homeward Bound’ and I just couldn’t resist (see what half a bottle of wine does to me!). I joined in and harmonised, to his delight, and we sang to an audience of one—a very appreciative Mr S. A perfect end to a pretty spectacular day.

The forecast for the following day still wasn’t terrific so, hoping for better weather, we decided on a bus ride (we did giggle a bit boarding the Fany bus). And once we’d battled our way onto the coach, through the usual mêlée which is a Romanian bus station (Queue? What queue!) we enjoyed glorious sunshine both for the journey and on arrival at our destination. We’d chosen a trip to north western Romania, and the old city of Satu Mare near the borders with Hungary and Ukraine.

Figure 18: Transylvanian Plateau journey

© SharpieType301 2018

Our bus journeys in both directions were enjoyable, if long at about three hours each way, giving us a good feel for the character of the flatlands of the Transylvanian Plateau. We passed through stunning countryside and old villages, passing numerous churches and roadside shrines. We saw single track ramshackle railway lines, old stations, tumble-down farms, itinerant honey producers, and more than one horse-drawn Gypsy caravan on the roads. Not exactly the highly decorated, intricately carved, brightly painted, Vardo you might expect to see.

Figure 19: Romanian Gypsy Caravan

© Emilian Robert Vicol, licensed under CC BY 2.0

Satu Mare developed on the banks of the Someș River (the same river as runs through Cluj), a meadowland area with trees suitable for wickerwork, plus poplar, maple, and hazelnut. In addition to a favourable position for settlements dating back to the Stone and Bronze Ages, the river made possible trade with coastal regions and beyond, so it became an important centre for craft guilds in the 13th century.

The city has some interesting architecture, including an early 1900s, 47m tall Turnul Pompierilor (Firemen’s Tower) but overall, it seems somewhat down at heel giving the slight impression of a frontier town, with fast food joints and casinos at every second step. Interestingly, although we saw no sign of this, Satu Mare has traditional links to fencing and has, apparently, raised the majority of European world and Olympic champions. We had seen a photo of the gorgeous old Dacia Hotel, which overlooks a pretty central park, one of the most beautiful buildings built in this style in Transylvania. Not quite so stunning now, she is a very faded grand dame. We weren’t entirely sure whether it was being renovated or condemned for demolition—very sad to see. Would we go back to Satu Mare? To be honest, no.

Our last day in Cluj dawned, and there was no debate, today we would go to the open-air segment at the National Ethnographical Park “Romulus Vuia”, whatever the weather had in store for us. We were quite tired, but we ambled along the small street where we were staying, onto the larger Strada General Ermia Grigorescu (past the garden with the daunting doggie, which opened one eye to look at us disdainfully, then went back to sleep).

Figure 20: Scary dog

© SharpieType301 2018

We then turned right, up the steep hill towards the entrance to the Park, to arrive at two minutes past ten, just after it opened. I’d love to say we had a laid-back visit, but no. Stopping only for a wee, and a drink from the water fountain, we walked and explored and walked yet more, finally leaving at four o’clock in the afternoon, tired, achy, sunburned, thirsty and raving about how marvellous this museum was. It was just unbelievably wonderful!

A bit of background. Many of you will know that I’m a Cardiff lass, and some of you will be aware of my penchant for museums and archaeology. I worked for a glorious spell at the St Fagans National History Museum (previously called the Welsh Folk Museum and, when I was there, the Museum of Welsh Life). Open-air museums are a bit of a thing for me, and one of my fondest memories is attending a Christmas Carol Service at the tiny Capel Pen-rhiw at St Fagans, this sweet structure used by the Unitarians as a meeting house or chapel from 1777. Another marvellously memorable trip was a visit to Skansen, in Stockholm, the oldest open-air museum in the world.

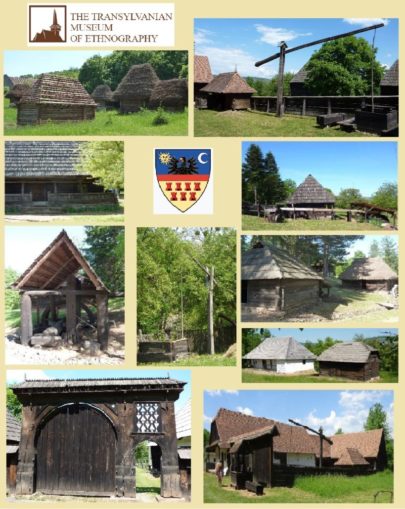

As we bought our tickets, I got into conversation with one of the museum’s staff, a lovely lady who spoke decent English. We picked up a guide leaflet (in French, there wasn’t an English translation) and, chatting to her, got a little information about the site. It isn’t huge, at around 37 acres (the sister museum at Sibiu is over six times the area), but it is jam-packed with buildings from across Transylvania which have been carefully disassembled, moved here, and just as painstakingly reconstructed to preserved them for present and future generations.

Figure 21: Village buildings

© SharpieType301 2018

It is a really beautiful park, green and rolling, the first open-air museum in Romania (only the sixth in Europe) with houses, farms, and churches, mostly built of wood. The way it has been laid out gives the feel of how a traditional village and its buildings might have coexisted. With many of the structures, it isn’t just a matter of seeing them from the outside, you can go inside too.

The first sector concentrates on technical installations and workshops from the 18th to 20th centuries. These illustrate traditional techniques, such as the water-wheel powered sawmill for woodworking, gold stamps for crushing rock to extract the metal, forges with huge leathern bellows for iron processing and blacksmithing, fulling- and felting-mills for wool and other fabric processing, areas for stone processing, working with clay to produce bricks, tiles, and ceramics, and then the agricultural processes, threshing and grinding cereals, milk processing to make cheese and butter, and mills and presses to extract oil or grape juice for wine.

Figure 22: Farming implements

© SharpieType301 2018

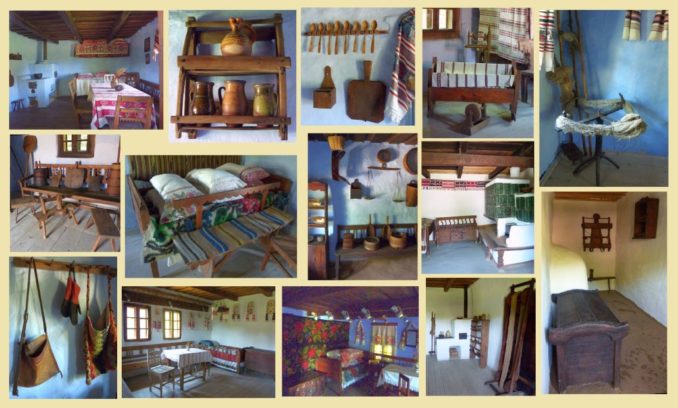

The next area is focused on traditional peasant villages and dwellings, each one subtly different as they represent distinctive ethnographical areas of Transylvania (in part, the designs reflect the local environmental conditions, from hot, dry plains to cold, wet mountainous regions). The buildings here date from the 17th to 20th centuries and have been set up to include the entire household inventory, both interior fixtures and fittings and the equipment used in the outbuildings. There are artisan cottages here with thatched or shingled roofs, some roofed with interspersed branches of fir trees and straw layers. Buildings for potters, woodworkers, for wool-craft and more. Typically small, but exquisitely decorated with pretty little touches, like a carved lintel, to make each one individual. These craftsmen and women made simple but beautiful utilitarian objects.

Typical everyday activities are demonstrated realistically, with mugs, jugs, platters and bowls, spoons, pans and cauldrons, lovely ceramic colanders. There is usually the sturdy family table in the centre of the room, with chairs (often beautifully and individually carved) and wooden benches set around the walls. Lots of straw-stuffed pillows for comfort, their edges decorated with colourful embroidered borders.

Figure 23: Farmhouse interiors

© SharpieType301 2018

The wooden beds with their crisply starched white linens (often beautifully embroidered, in delicate white patterns), and heavy woollen blankets. Some beds are curtained with thick, dense hangings to cut out the cold draughts, others built into a cosy nook for the same reason, the wood darkened with age and use. Cribs, on a gently curved base, or suspended from the rafters to allow the baby to be rocked to sleep. A tiny glimpse of rural life, from across Transylvania.

Then there are the farmsteads, on a much larger scale with outbuildings for animals, for farm tools, and for storage. Typically constructed around a central yard, with high, ornately carved wooden gates. Dip-wells, a long pole suspended from an upright to lift a water bucket, are common, often with a wall surrounding them, presumably to prevent small children and animals from falling in!

The original thematic outline was to include an ethno-botanical zone around each farmstead, at the ‘village’ borders with traditional crops and related buildings, and an ethno-zoological area with pastoral buildings and local breed animals. Sadly, for reasons unknown this never fully came to fruition, but there are areas planted with typical crops and a few goats, a nanny and two kids. These are an absolute delight to watch but have a curious background. The nanny goat was left behind (as you do!) after a charitable event to raise funds for agrarian projects in Africa.

Quite soon afterwards, the museum realised that she came complete with an added bonus, kid No. 1. Then kid No. 2 was ‘donated’ to keep the others company, and because its mother was unable to feed it. They are now pampered museum pets. Speaking of kids, there’s a kindergarten in the grounds of the park, and the lucky children have this wonderful green space as their playground. Can’t see Health & Safety letting that pass muster in Blighty!

Figure 24: Kids

© SharpieType301 2018

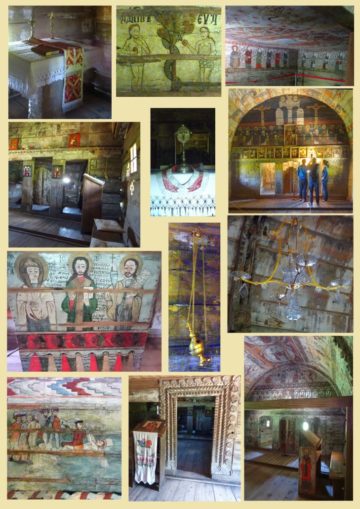

Then there are the churches, three of them which have been lovingly reconstructed at the site. The Church from Cizer-Salaj is considered one of the most beautiful wooden churches in all Transylvania. It was built by Vasile Ursu Nicola (known as Horea). The words ‘worked by Ursu H’ are carved on the nave’s beam in Cyrillic letters. Horea is considered a folk hero who helped Romanians to see themselves as a people and a nation. He led the two-month-long peasant rebellion that began in the Metaliferi Mountain villages in late 1784 and ravaged the whole of Transylvania, resulting in the destruction of many castles and manor houses. Sadly, the rebellion (thought to have inspired the French Revolution) was brutally crushed, and Horea executed. He was publicly broken on the wheel, and his body cut into pieces, to be scattered at various villages to serve as a warning to future would-be rebels.

Figure 25: Churches

© SharpieType301 2018

Each of the churches is quite extraordinary, being entirely constructed from wood, with tall, slender spires and steep shingled roofs. The roof extends well past the line of the wall, to give a sheltered space, often with a veranda. The wood is charmingly carved, a rope-work motif is common. The doorways are exquisitely decorated with elaborate carving. Inside the walls and high, vaulted ceilings are painted in bright colours, depicting Biblical scenes and pictures of the saints. Simply lit (candles most often) they must be extraordinarily atmospheric and even though some of the paintings are faded and some parts have been lost, they are absolutely gorgeous.

Figure 26: Church interiors

© SharpieType301 2018

In the first church we entered, there was a group of three people, one with a powerful light, one with a big camera taking close-up shots, and a lady directing them. It looked like a conservation survey in progress, so I walked over to speak to them. The woman was indeed a conservator, and when I explained that I too had trained as an archaeological conservator, she told me (and showed me) that although there had been a major restoration project less than eighteen months before, they have a localised woodworm infestation. A massive problem, this! The group were there to document the extent and plan the best way to treat the worm while preserving the fragile painted surface. I wished them well with this. It won’t be easy and needs to be addressed quickly.

By the time we left the museum, we were gasping for a drink, and rather footsore so glad the walk was downhill. Definitely ready to sit to watch the world go by. We bumped into an English couple we’d met before, who suggested somewhere for dinner on our last night in Cluj, before getting on the train for the long ride to Bucharest and the remaining days of our Romanian adventures. A brewery, a rather special one at a location steeped in history, whose beers are imbued with the character of this city. It seems Cluj was ready to surprise us one last time… but that’s a story for the next episode.

© SharpieType301 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player