How could any true traveller ignore the lure of a name like Thorne Waste? It could be the title of a Brontë novel, or the kind of place the Hound of the Baskervilles was locked up in between eating hikers lost on the moors. And there is another curious thing about it. On my wall map of England, which is huge enough to show every country lane from Berwick to Land’s End, Thorne Waste is the largest blob in the Midlands almost without any settlement features. It sits there on the map of the East Midlands like a bald spot, free of roads, railways, villages or even hamlets. Just a couple of arrow-straight drains cut diagonally across it.

I bet you are wondering, where the hell is it? Well, your clue is the word “drain.” In one boring line, this 8,201 acres tract east of Doncaster is part of the largest area of lowland raised peat bog in the United Kingdom. It was brought to the surface in the 17th century by Cornelius Vermuyden, the great Dutch drainage engineer who reshaped several counties through massive land reclamation — in this case South Yorkshire. It remains a pretty boggy place, which has long discouraged settlement. For centuries, all you could do here was cut peat. The last firm to work the “moors,” as this area is known locally, was Fisons, and they have left a spooky and magnificent ruined factory shed right the middle, where you can role-play your Reservoir Dogs fantasies.

I very much like this part of England, with its glinting dykes and canals, its solitary muntjacs and marsh harriers, its plain, lonely brick farms, its huge fields, its bleak horizons. (But not so much the sodding windmills which now ruin many fenland vistas). Many times I had ridden past Thorne Waste, always wondering what lay beyond the plantations that now screen the interior off, before I got out a one-inch map and actually ventured into it.

I began my visit on the edge, at Medge Hall signal box, where horse-drawn tramways of the peatcutters once joined the main line. The signal-man told me the Waste is a weird place, prone to mysterious weeklong fires (peat is known for occasional spontaneous combustion) and dotted with deep, dangerous old workings you really would not want to fall into. It’s a nature reserve now, he said, but being unpoliced and empty, prone to deer-poaching. There I left him, with his bunk-bed, sink, microwave and pile of Suns as he waited for the next Scunny train.

In official eyes, Thorne Waste, exhausted by peat-extraction, did not cut the mustard for being a nature reserve. But it was championed by an early 1970s bunch of eco-warriors called Bunting’s Beavers who interfered with Fisons’ operations with various acts of sabotage targeting the drains. I am instinctively against this kind of vandal-activism, but have to admit in this case they probably saved Thorne Waste from being turned into another new town or regional airport.

The only place I have been to that is like is Thorne Waste is Foulness. Without amenities, traffic or villages, and just a few farms, it really was like stepping back into another age. The lanes were tarmacked, but the only people I met were a dog-walker from one of the farms, and a birdwatcher from Holmfirth who was “here for the dragonflies.” I would imagine there’s a lot of unusual wildlife in this unique environment.

Thorne Waste felt less remote, though, than I had hoped, as you were always in sight of civilisation in the form of windmills and a power station across the Ouse at Goole. The fenced off bits with the inundated peat workings really were frightening, though. Fall into one of those holes and nobody would hear you.

Moats

Once upon a time, most big houses in England had moats. Even after the turmoil of mediaeval times, squires still kept them topped up because they were a deterrent to burglars. Not a very good one, of course. But if you had to choose between wading through a full moat in your Fred Perrys and picking an equally rich-looking place without a water barrier, you would probably go for the latter.

Today, the few places that keep their moats filled tend to be stately homes and other A-list buildings with tourist brochures. Examples include the Bishop’s Palace at Wells, Rye House in north London (the Plot place), and the glorious but almost unknown Elizabethan manor house at Harvington, Worcestershire.

But what I like to find is the humble no-name moats that are still reasonably complete and fully watered simply because time forgot to pull the plug on them. These are rare. After an extensive trawl of my cycling notes, I can come up with only two — Metham Hall Farm on the bleak south bank of the Humber, not far from Thorne Waste, and Moor Court Farm at the back end of Lewknor, South Oxfordshire. There must be more, especially in Essex, a county with a full ditch or two, but that is all I can claim to have seen and dipped a finger in. I am not counting severed limbs of old moats that are now just ditches and no longer surround anything.

Nor am I counting dry moats, of course. But to end this section, I do want to say something about them. If you want to see a profusion of dry moats, the place to go to and waste an afternoon poking around village hedgerows is Scredington, Lincolnshire, which for some reason has a half dozen of the things “within a 1.25km radius.” I have no idea why.

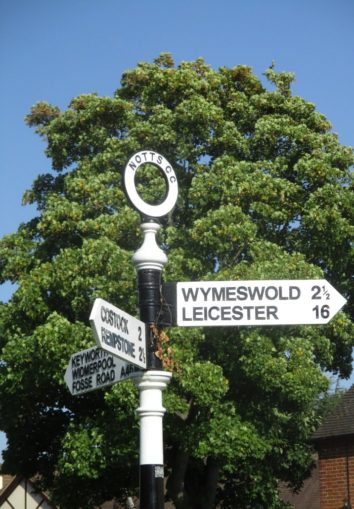

Wysall

Wysall is a pleasant village in the Nottinghamshire Wolds, not far from the little cheese-making town of Wymeswold, which everyone thinks is the creation of a dairy marketing team but which does actually exist. (And jolly nice it is too, though I haven’t seen a Wymeswold cheese for donkey’s years). All the villages round these parts are lovely. But Wysall caught my eye for two reasons. Firstly, because of its manor house. A delightful Tudor job (“Timber frame, rubble, render, red brick, some ashlar,” notes a standard source) but interesting also for its odd location, in a little cul-de-sac modern housing development. There it stands, among the neatly cropped lawns and gleaming Audis. It is privately owned. According to villagers, it had nearly been knocked down two decades before as the old walling with its half-timbering and stonework had been hidden by rendering. Presumably the little estate was built on the manor park.

The other interesting thing about Wysall is that is a Thankful Village, one of just 41 British villages to emerge from World War 1 without losing any of its young men at the front. Twelve Wysall men signed up over the five years of the war (it is a village of over 300 souls today), seeing action in northern Europe, Ypres and the Somme. One was injured, but was able to return to farm work.

I have only ever visited a few Thankful Villages, and I have wondered how it feels on November 11 in such a place when there is nobody to remember. Do Thankful Villages have anything like “survivors’ guilt”? I asked the two villagers I met by the manor house this. “No,” was the first reply — it was just like in any other place. The other villager looked at me and said, “What’s a Thankful Village?”

Perhaps it was indeed a stupid question.

For my free downloadable pdf travel books on Europe and East Asia, please visit this website: https://www.itabibito.com/.

© text & photography Joe Slater 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file