In this extract from his book* my uncle describes his time as a war correspondent with the Army’s official newspaper Union Jack in the latter stages of World War II. Jerry F.

In World War II the Army newspaper was born. This was a fully-fledged newspaper serving the troops in battle. It was staffed by journalists in uniform: journalists who were soldiers first and reporters a long way afterwards.

These reporters in battle-dress saw war in close-up. They flew with the bombers and rode with the tanks and hit the beaches in landing craft. They saw war in all its moods.

One of the first and most famous of these army newspapers was Eighth Army News. Born in the Western Desert and edited by a tall, lean young fanatic called Warwick Charlton it followed the fortunes of the legendary Eighth Army all the way from the Nile Delta, in Egypt, to Bari, in Italy.

It was very much a local newspaper. It jealously guarded the reputation of its Army: it was full of little private jokes that were pointless unless you wore the white crusader’s cross of the Eighth on your sleeve: and the sunburned Desert Rats swore by it.

It was Charlton’s proud boast that he never missed an edition. On one desperate occasion – it was after the fall of Tobruk – a high-ranking staff officer found him at a desert road-block running off on a hand-press a special edition announcing the fall of Tobruk, and handing out the still wet copies to the battle-dazed troops as they poured east away from the doomed city.

The staff officer thought this was in very poor taste, and said so with some heat. Charlton was unmoved.

“My readers expect the truth from the News,” said the soldier-editor. “And that’s what they’re going to get!”

In time Eighth Army News was taken over by Union Jack, though it remained the Eighth’s own newspaper until that proud Army was finally disbanded in 1946.

Union Jack was something unique in journalism. It was the first newspaper to be sponsored by the War Office, who created a complete Army unit – the British Army Newspaper Unit – to print and publish it. For nearly two years it was the only source of news many servicemen had. It went up with the rations to isolated units in remote places. Once it was actually delivered by air to troops advancing into battle. And at one time it had over a million readers.

Its alleged origin is fantastic enough to be true. The story goes that Winston Churchill, during the Casablanca Conference, opened his eyes one morning to find a strange-looking newspaper on his breakfast tray.

“What is this?” he asked, holding it up curiously.

They told him it was The Stars and Stripes, the official newspaper of the American forces.

“And where is the British forces newspaper?” enquired the Prime Minister, somewhat acidly.

They explained, apologetically, that as yet there was no British forces newspaper.

“Then let there be one!” growled Mr. Churchill.

And of course, there was. Forthwith and at once.

A certain infantry captain named Hugh Cudlipp, who before the war had edited the Sunday Pictorial, was recalled from the desert and ordered to start a Forces newspaper.

In Cudlipp they had found the right editor for the job. A dark, dynamic little Welsh terrier of a man, he flung himself furiously into it; barking and biting at Authority until he got exactly what he wanted in men and material.

It is unlikely that any newspaper in history has had a more brilliant, colourful or, by Fleet Street standards, more expensive staff of writers and pressmen than the Union Jack in its short but hectic life.

Given a free hand to recruit from anywhere any man who could be spared, Cudlipp rapidly got together a unit made up of officers and men who, in peacetime, had worked on some of the greatest newspapers in the world. There was no formality on Union Jack. And, as the paper rapidly expanded, very little room for rank. A young subaltern, who had just finished his apprenticeship on a small weekly paper when the Army took him, might find himself nominally in command of a sub-unit which included a sergeant who in peacetime was night-news editor of the Daily Mail, a lance-corporal who had been foreign sub-editor on The Guardian and a couple of privates, one of whom had seen happier days as leader-writer on The Scotsman and the other a famous Fleet-street film-critic.

The first editorial office of Union Jack was a corset shop in Algiers. But as the Army moved forward, crossed the Mediterranean, and invaded Europe by way of Italy, Union Jack moved forward with it. Soon it had its headquarters in Rome: and was publishing local editions in Algiers, Tunis, Catania, Naples, Bari and Athens. The last edition was published in Venice – and distributed by gondola!

Cudlipp’s orders to his editors were simple but exact: they were to publish as close to the front line as possible.

His editors wanted no encouragement.

Often a local edition would move into a front-line town and open up before the streets were clear of fighting. Fred Redmond actually ran off the first number of the Florence edition while the Germans were still sniping at him from the opposite bank of the Arno.

News-gathering for Union Jack was wonderfully unpredictable. You might find yourself sent off on a routine weekend assignment and not see your editor again for six months. You might go up the line to write a cosy ‘gossip piece’ about a new unit just out from home and find yourself involved in a full-scale invasion.

That happened to me. In July 1944 I was helping Ralph Thackeray, late of The Guardian, to get out the Algiers edition when a letter arrived express-airmail from my editor-in-chief in Rome. Cudlipp never wasted words. All it said was:

“I have already cabled Thackeray to send you as soon as possible to see me in Rome. There are several jobs I want you to do here that you will find interesting.”

That last sentence was a real masterpiece of understatement. A week later Operation Anvil smashed in France’s back-door. Just twenty-four hours after that I dropped in from an American Mitchell bomber to see how things were going.

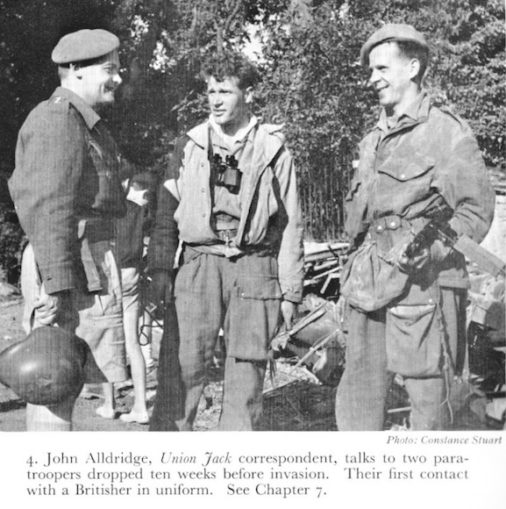

John Alldridge, Union Jack corresdondent

Constance Stuart via G.Bell & Sons Ltd – Copyrights lapsed

“Just stick around for a few days,” was all the ‘briefing’ Colonel Cudlipp had given me. In fact I stuck around for four and a half months. That assignment took me right up into Germany and back to Italy by way of Britain. Mine not to reason why. “Stick around”, Cudlipp had said. So I stuck.

It was one of those heaven-sent, wide-open assignments where it is left to you to find your own stories. I was completely on my own. All I was allowed to take with me were my typewriter and a small haversack. I landed in tropical shorts and shirt. I was still wearing my shorts in November.

But I was not quite without friends. I carried orders from American Public Relations which gave me leave to make use of their Press Camps – for I was officially attached to the U.S. Seventh Army. The Americans, as always, were wonderful friends: and wildly generous in their help. They supplied me with food, shelter and transport. And – what was even more important – a means of communication. More than once they laid on a special courier plane to fly my brief dispatches back to the beachhead for onward transmission to Rome. On that assignment I must have used practically every form of communication known to man – from short-wave radio to pigeon-post!

For convenience, war correspondents in the field work in small groups of two or three together. It’s a good idea, not only because it saves petrol and fuel; it is reassuring to have a friend breathing down your neck should you suddenly find yourself in a tight spot.

Keeping check on the activities of these highly-mobile reporting teams became quite a problem. As I noted in one of my earlier dispatches from Southern France:

‘Perhaps the most harassed officer in the 7th Army at this moment is a certain American Brigadier responsible for the movements of the forty or fifty war correspondents operating in this zone.

‘Every morning they disappear, four to a jeep, and there is no indication where they will be by nightfall. Like Xerxes, he counts them all at break of day and when the sun sets where are they?

‘Five have been missing since Sunday. Now we know that three were taken prisoner by the Germans before the fall of Marseilles and the other two have just wandered back from Switzerland. Others have drifted in by twos and threes from all over Southern France. There was nothing to stop them. The only Germans they found in a day’s scouring were miserable little hunted parties who have been hiding in woods and are eager – so terribly eager – to give themselves up.’

I teamed up with Rupert Downing, of the B.B.C. Rupert was an eccentric. One of the smallest correspondents in the game – he stood barely 5 feet high – he incidentally had a tremendous sense of occasion. He wore a splendid fancy-dress uniform which he had designed for himself. He wore a beretful of badges – a la Montgomery – and carried a formidable armoury tucked in his belt.

He had lived for many years in France before the War and spoke French like a Frenchman. He understood the French temperament, and they certainly understood him.

His special delight was to race on ahead of the liberating Allied armies, select the next town or village due to be liberated, descend on the town just about lunchtime, and announce the great news in ringing tones from the town-hall steps.

The reaction was always the same. There would be scenes of wild rejoicing. Bells would peal from all the steeples. Flags would fly. The prettiest girls would queue up to kiss us. And we would be led off to a hastily-arranged Liberation lunch in the town’s best hotel as the guests of the Mayor and Corporation. We liberated a great many of the villages in Central France like that!

Rupert was the proud owner of a little red Fiat, which he called ‘Fifi’: in honour of the French resistance fighters, or ‘F.F.I.’, who had presented her to him.

In Fifi we were free to roam at will all over Southern and Central France. And roam we did. For this sector of the war was wide open. Taken completely by surprise and already heavily committed in the North where General Eisenhower’s forces were beginning to break through, the Germans had withdrawn hastily. The Americans followed up fast. Too fast, as it turned out, for very quickly they ran out of petrol; and in a few short weeks an invasion which had started by advancing several hundred miles in a single day slowly ground to a standstill.

With the Americans furiously marking-time the job of continuing the fight was left very much to the French partisans. They had been waiting five years for just such a chance. But for all their fierce courage they were pathetically short of arms.

In the Seventh Army Press Camp we had heard a good deal about these civilian-soldiers of France and of their magnificent fight. Since there was little happening on the official front, Rupert and I decided to go off on our own and report this strange unofficial war.

We drove down long white roads where nothing moved and life for a time seemed to stop and the people moved about in a daze, still shocked by the coming of peace. For them the war was over. But they could not believe it. They seemed to be living in a dream that was so good that they didn’t want to wake up.

In one of these small towns I sat at a café table and scribbled a dispatch for Union Jack.

‘You sit down at a café table, slip your goggles up into your hair and wipe the dust from your ears,’ I wrote.

‘You order a bottle of wine and wearily light a cigarette. The circle of chairs round your table slowly fills. You are too tired to talk and they are too shy to speak. So you both sit there and smile at other.

‘You hand round cigarettes. They are taken with polite eagerness and examined for the brand. That breaks the spell. “Cigarettes Anglaises! Vous etes Anglais?” And the flood breaks over.

“Me know London. Me blesse – ‘ow you say? – wounded – with Anglais at Cambrai. Best friend of me live Manchester.”

‘And then from the back of the crowd, where they are shyly watching, they are pushed forward to meet you. The real heroes of France. The little people who in a thousand newspaper stories for four years have stood like giants. Those almost legendary figures, the men and women of the Resistance. For so long we have known them only as “Mlle X” and “Peter Pan” and “Chariot”. Now they are coming out of the shadows and we are meeting them for the first time.

‘I think Sacha and Annie are the bravest young married couple I have ever met. Annie is small, dark, vivacious. Sacha is tall, blond, broad-shouldered. Before the war they were Paris journalists. When Sacha escaped from his prisoner-of-war camp he joined Annie and together they started a typewriting and duplicating bureau in Lyons. At least, that is what they told the Gestapo when they called.

‘The typewriter tapped away in the little office all day. Harmless, innocuous stuff. Bills of sale and business letters. After midnight, behind locked doors, the typewriters clicked to a different tune. The typewriting bureau became a secret news agency.

‘News picked up by clandestine radio, from duplicate copies stolen from the files of Vichy agents and cabinet ministers, went out to 200 news agencies. Twice a day for nearly four years Annie walked downtown to the markets along streets patrolled by the Gestapo. At the bottom of her string shopping bag, hidden among the potatoes and the fruit were the facts and figures, the damning evidence, which must be smuggled away.

‘And the next day the editor of an underground newspaper in a faraway town would receive letters from a greengrocer, a customs officer, a tailor. Inside the envelopes was the material for a leading article. . . .

‘Paul is a patriot of quite another sort. He is the typical French provincial of a thousand cartoons. Round as a football. Voluble. Explosive.

‘When the war came to Voiron he grunted and growled but carried on with his radio repairing. He didn’t understand much of what was going on in Paris. He wasn’t interested in politics. But he hated the Boche from the bottom of his stomach.

‘Then he began, unwittingly, to do the forbidden thing. He mended the radio of a neighbour who was on the Gestapo suspect list because he had been listening to the B.B.C. The listener was taken away and was never seen again. Paul’s shop was blown up by a gang of fascist hooligans. And the Resistance had gained another recruit.

‘Cold fury in his heart, Paul set up shop secretly in the wine-cellar of his brother-in-law. There for three years he has been mending free of charge all the radio sets brought to him.

‘Proudly he showed me his repair-kit. Cigar boxes filled with spare parts unobtainable in France these days. When you ask him where they came from he rolls up his eyes and grins:

‘From heaven. From our friends the R.A.F.’

‘These then, were the little people. The anonymous thousands who had never lost heart. And because of it had kept alive the spirit of France.’

Meeting them was a moving and humbling experience. I brought back few medals from the war. But I treasure today something infinitely more precious. It is a small, ragged Union Jack. It was made out of scraps of coloured silks in secret behind shuttered windows by a French woman who never lost hope. One day, she knew, the British would come back.

When that day came she was ready with her little homemade flag. As we rode slowly down her quiet street she ran out and threw her arms in front of Fifi and fastened her flag to the radiator cap; and there it flew proudly until the end of the war. A Frenchwoman’s “merci!” to Britain.

It was a strange time. Trying to catch up with a war that had got away from you. And when you found it at last it would be a short, bitter affair of amateur soldiers in scarecrow uniforms against a small, weary professional rearguard, almost asleep on its feet.

For days we had been driving warily through open country, unmarked by war, which according to the B.B.C. bulletins, picked up on Fifi’s’ radio, was still very much in German hands.

Sometimes we would even see Germans. And a dozen times a day there would be a nasty moment when a few field-grey uniforms would come scampering down from out of the woods that fringed the roads.

But always they were deserters. Poles or Czechs or Rumanians who had given up and only wanted to be marched off to a comfortable prison camp where the French couldn’t get at them. They would beg us – sometimes with tears in their eyes – to take them prisoner. But we had to push on. We had a war to find.

Then one evening just before dusk, on the edge of a forest in a fold of the Jura mountains we found it.

And this is the story I wrote:

A Jura Village, Friday

‘I am writing this by candlelight in the village school. They have stacked the old worn desks in the corner; but there on the blackboard is still scrawled the triumphant Liberte, Fraternite, Egalite.

‘I am writing this pad-on-knee because there is very little room. It is nearly midnight. In four hours I expect to witness the strangest battle of my life. A battle between the encircled German garrison behind its blown bridges on the other side of the river, and the men of three small French villages who have sworn to be in the town by dawn.

‘The parish priest has spread an old Michelin road map of the district over the teacher’s desk. The parish priest is the battalion’s intelligence officer. He is young, dark, clean-shaven. In 1940 he was a sergeant-major in a hard-fighting infantry regiment.

‘Tomorrow, still wearing his cassock, his head protected by my steel helmet, he will go into action with his congregation.

‘The commandant – he holds the equivalent rank of major – has his company-commanders around him. He speaks crisply, wasting no words. The commandant is not a local man. Appointed by General Koenig’s orders he came from Lyon last week to replace the former commandant, killed by a sniper’s bullet. Local prejudice is strong in France; but these three villages have accepted his leadership without comment. In peacetime he is a civil engineer, a lieutenant in the old Regular Army reserve.

‘Today, wearing a British beret, an American wind-cheater, and blue jeans, a revolver lashed round his waist with string, he commands a thousand men.

‘But he is something more than a soldier. He is a civil administrator too; the symbol of law-and-order in this village which has known none since the Germans left two days ago. A few hours ago they dragged three wretched women into the schoolyard. They had been friends of the Germans, these women. The village gathered round to watch the grisly hair-cutting. The commandant stopped it with two angry words.

‘He outlines his battle-plan to me. I am impressed by the military simplicity of the whole thing. Tomorrow morning two companies – the Compagnie Yser and the Compagnie Verdun – will go through the woods and ford the river. Compagnie Dunkerque will put down supporting fire.

‘Supporting fire! That’s ironic. The whole battalion has only five machine guns – all of them Brens dropped by the R.A.F. – and a few captured German automatics. The two attacking companies will go in with hand-grenades, knives, shot-guns, Stens and revolvers.

‘No support will be possible from the regular Allied forces. We are too far forward. This will be a fight to a finish between a few well-armed but desperately tired Germans fighting a delaying action and a thousand ragged but still disciplined Frenchmen, with cold fury in their hearts.

‘Earlier in the afternoon I inspected the three companies drawn up on parade.

‘”An army of scarecrows, eh?” grins the commandant. I look at them – at the red-white-and-blue armbands hastily made out of bandages – at the pathetic scraps of uniform – a British battle blouse, a gas cape, an old French infantry tunic, a rusty helmet or two and – heaven knows how it got there – a Scots balmoral.

“An army of scarecrows?” Well, scarecrows maybe. But so were the ragged armies of the young Republic that shocked the world at Valmy. And I know I shall be in good company tomorrow. And I find a sneaking pity for the Germans waiting for them on the other side of the river.

‘There was a heart-warming cheer when they wheeled out their one “armoured car”. The work of the blacksmith, a village genius. The “car” is an old Fiat chassis reinforced with steel plates and bravely camouflaged. The blacksmith lost a leg on the Somme. It is his share in the village war effort.

‘For the whole village has been mobilised for this battle. We know the strength of the enemy thanks to the sheer cold courage of two of the bravest young women I have ever met.

‘This afternoon they calmly wheeled their bikes across the broken bridge and cycled round the enemy-occupied town. Then they returned with their information.

‘And a proud man is the local draper. A pigeon-fancier, he is now the Signals Officer and his birds are on active service. The grocer and the innkeeper are the quartermasters. And every barn is a billet and packed with partisans. Yes, this is a scarecrow army. But it is destined to scare more than crows. . . . ‘

The following morning Rupert and I watched the attack go in from the belfry of the village church. We watched it go in in three waves that never faltered. The battle on the other bank was short and bloody. No prisoners were taken.

As the first rosy fingers of dawn touched the Eastern sky towards Germany it was all over. Then we were driven out of the belfry by the clanging of the bells announcing victory.

We left the church and walked down the neat little village street. There were no flags as yet. But an old lady stood at her cottage door and offered a tray with brandy on it and invited us, timidly, to drink. We drank and thanked her and walked on out of the village. The bells were still ringing. But we never looked back. Suddenly we had had enough of war . . . .

* Special Assignment by John Alldridge, published in 1960 by (the long-defunct) G Bell and Sons Ltd

Jerry F 2022