More notes from 45 years of cycling

If you are following this series, you will know that my kind of curiosity is one that is still making money, or at least providing a public service unconnected with tourism. First up today is Chetham Library.

Even if you live in Manchester, chances are you haven’t heard of this wonderful place by Victoria Station. I didn’t actually stumble on it, but heard about it and cycled there over 20 years ago, which is when the following was written.

Chetham Library was first described by the seventeenth-century traveller Celia Fiennes. You can’t share a piggin of beer with the pupils as she did in the cellars of Chetham’s school, but you can still use her as a guide to the library, the oldest in the English-speaking world still open to the public. Apart from the electric lighting, this L-shaped panelled chamber has hardly changed since her visit in 1698. It was the first time that I had ever opened a seventeenth-century book, or, for that matter, sat in a seventeenth-century chair at a seventeenth-century reading desk or browsed among seventeenth-century oak shelves. These contain 60,000 volumes published before 1851, some still chained and stacked spine inwards in the old fashion. “People tell me,” the receptionist said, “they walk past here every day on their way to work, but had no idea you can go in.”

The old library is one of two separate establishments that evolved out of Chetham’s blue-coat school, created by endowment by Humphrey Chetham (pronounced “Cheat ‘em”), a cloth merchant who died in 1653. The other, which I didn’t visit, is Chetham’s School of Music, Britain’s largest specialist music college. Originally Chetham’s was a fifteenth-century manor, and later a college for priests; the surviving buildings include a baronial hall that has been called the finest in the country. It is used for concerts by the student musicians.

The library’s interior dates from the 1650s. Among the volumes it has are Galileo’s Systema Cosmicum (1646), and Newton’s Principia. As a store of early original texts of western science, Chetham’s can have few equals: Copernicus, Kepler and Brahe are also here, as well as a mediaeval copy of Matthew Paris’ Flores Historiarum. This must also be one of the most important public libraries of works in neo-Latin — the Latin of scholars after the Roman age.

With resources like these, Chetham library became a focal point of Manchester’s intellectual life, and no doubt a valued refuge from the smoke, noise and squalor of its commerce. One of the regulars was one Karl Marx, who struggled there with the seventeenth-century English of works such as Free Trade, or the Means to make Trade Flourish by E. Misselden (a forerunner of Adam Smith). Engels studied there too. You can sit in the alcove he liked best, because, he wrote to Marx, “the window glass is prettily tinted and the weather is always fine here,” and wonder at the enormities that began in the minds of these Chetham readers, in this mediaeval manor.

Chetham is perhaps the only corner that remains of the timber-framed Manchester Celia Fiennes saw in 1698. It’s close enough to the city centre to have felt the IRA bomb blast, from which it was protected by its defensive courtyard layout, even though a modern annex lost windows.

Rawtenstall and Haslingden

Victoria Station is the gateway to Rochdale, itself the gateway to the steep valleys of the moorland cotton belt of Lancashire. Typical of this country is the Rossendale Valley — which looks less romantic than it sounds — where, late one afternoon, I came to Rawtenstall, an old cotton town with its characteristic mill hulks, tall chimneys, views of high moors and sounds of bangla music thudding out of Kias. After a superb quiche at Manning’s the confectioner, who despite being in the process of closing for the day uncovered all their stock again for me so I could buy a bite, I wandered about a bit the centre and so stumbled on Britain’s last temperance bar.

Fitzpatrick’s really had been in business since the age of temperance, the young manageress said, although the present décor is a retro refurbishment using original shelving. It sells a kaleidoscopic range of cordials from Mr Fitzpatrick’s juice works down the road, along with milk-shakes and confectionery. Temperance bars could be found all over the country at one time, but, like the roadhouse pubs of the 1930s, have almost completely vanished now. (One place where you can at least get a feel for those puritanically improving times today is the factory town of Port Sunlight on the Wirral.)

Fitzpatrick’s is not exactly a secret — the manageress told me she had been interviewed recently by Radio 4. I said I thought this idea could catch on, especially if they targeted the Muslim market. She said they did actually get some Muslims, who preferred it to Costa.

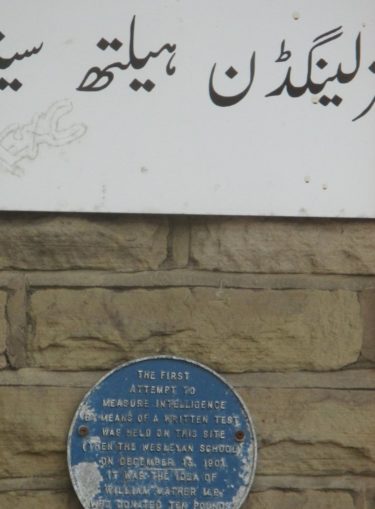

Just up the road is another old mill town, Haslingden, with another curiosity. An overgrown industrial village from the cotton days, Haslingden was the birthplace of written IQ testing, of all things. Had I been driving, I would never have seen the little blue plaque, which said “the first attempt to measure intelligence by means of a written test was held on this site (then the Wesleyan School) on December 13, 1901. It was the idea of William Mather MP, who donated £10 in prize money.”

Barrow-in-Furness

“One hour away from the M6,” Barrow’s council laughingly boasts. (Make that 90 minutes if there is any problem on the awful A590 out of Furness). Outside Cornwall, is there anywhere in England that size from which it takes longer to get to a motorway? That is only part of its image problem. It’s also widely considered an ugly industrial dump full of inbred chavs. And that is from a Barrow native, who was a neighbour for a long time.

I look at the place through different eyes. This is surely the best remaining example of a Victorian factory town that is still making things. It’s a classic of the type. Think grids of terraced streets, 1950s-style corner shops, narrow alleyways, slate roofs and rows of dead chimney pots. Beyond the rooftops, close enough to close off every seaward vista, are the hulking ship-building sheds. There are almost no modern high-rises; nearly all you can see is Victorian or early-mid 20th century. Much is also built of the local “Hawcoat” sandstone, which is almost the same shade of angry red as weathered brick, adding to the austere, monolithic appearance. This really is as close as you going to get today to the smoky, grimy old England Lowry depicted.

So Barrow is no Stow-on-the-Wold. But I seek out places like this. I see beauty in slate roofs and Yorkstone paving slabs shiny with rain, and even in those neat terraces of two-ups-two-downs, the cottages of industry. I have never thought of them as slums. I like the fact that thousands of Barrows men troop off every morning to real jobs, building or fixing nuclear subs on the waterfront at the vast BAE works. And I like the fact that the population is almost entirely West Cumbrian and the shops are nearly all staffed by locals, even if some of them do keep rabid Rottweilers in the backyard and leave beer-cans all over the park grass. There is a real community, and it shows. After Lancashire, I think Cumbria generally is the friendliest region of all England.

I like too the fact that Barrow is identified with a single product. What other town in England can point to something as gob-smackingly powerful, huge and complex as a nuclear submarine and say, “We made this?” I was there during the hiatus between the two lockdowns, and was informed by a newsagent that the full BAE workforce is 9,000, but now reduced to 2,500 during the pandemic because they had a headcount limit in each shed. Unemployment has spiked. But it’s always one crisis or another in neglected West Cumbria. Doubtless they’ll pull through.

For want of space, I’ve said nothing of Walney Island, Vickerstown or Barrow island, the village at the heart of the town. Instead, I want to end with a few lines on the West Cumbrian coast to which Barrow is a gateway, the forgotten western fringe of the Lakes.

You leave Barrow by Dalton-in-Furness, which has its own little castle bang in the middle, a cube of stone that once defended the whole area, and a ruined abbey on the outskirts. The coastal belt is served by a charmingly knackered and slow single-track railway that gives fabulous views over the Irish Sea and, at its northern end, the pasturelands outside Carlisle. The line is a relic of an important industrial zone centred on Whitehaven and Workington, which dug coal and made rails for the world. Before the industrial age, this was the fiefdom of the Earls of Lonsdale, who still have one of the largest estates in England. Yes, the original Lonsdales, the family whose name ended up on the boxing belt and the clothing line. (Long story, worth looking up). Today, the local employer the length of the coast is Sellafield and its dependent industries. The “plutonium factory,” a local called it. It is actually a nuclear garbage-recycling plant, and apparently is or was also capable of weapons manufacture. Whether or not for the subs at Barrow, I don’t know.

For my free downloadable pdf travel books on Europe and East Asia, please visit this website: https://www.itabibito.com/.

© text & photography except where indicated Joe Slater 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file