Simon Marmeladov was in Greece learning Greek. Because Santorini tends to be rather hot in June, the lessons started at seven in the morning and finished at eleven. This arrangement suited Simon who had become an early riser since he had turned his life around and become a British dissident. For the first three days after his arrival in Santorini, he had eaten lunch at a small taverna near the harbour, but yesterday he had had an unpleasant experience. A young Swede, about half Simon’s age, who introduced herself as Pernille, had taken an interest in him. Moving to his table without any invitation, she had launched into a homily about global warming and all its supposed destructive effects, as if heat in Greece in Summer was something new, going on and on while Simon listened in amazement to the nonsense her rather large mouth spouted. Suddenly, for no reason Simon could fathom, she erupted in idiotic laughter and it was then that he caught sight of a black metallic stud embedded in her thick tongue, which for some reason sent a jolt through his spine. At first, Simon told himself he had imagined it, but he had another discreet look as Pernille started jabbering again: a stud was indeed planted bang in the middle, making her tongue look as if it were afflicted with some strange disease, which somewhat killed off his appetite. Although she did all the talking, Pernille seemed to like Simon enormously and suggested at the end of their meal he had originally intended to eat alone that they meet again in the evening. Simon had become a shy, withdrawn, even ascetic man since his last release from prison more than three years ago. He had realised since then that the daring and braggadocio of his early life had been nothing but a pose to fit in with his criminal environment.

“Only a mad, raving, self-mutilating liberal would take a fancy to an old wreck like me,” thought Simon.

He made a few non-committal noises, paid his bill quickly and hastened to the relative safety of the tiny fisherman house he rented in a quiet street nearby.

That night, Simon was visited by a nightmare about Pernille’s black-studded tongue. As this is a family-friendly site, I shall refrain from recounting its contents. Suffice it to say that our friend woke up at dawn screaming and covered in cold clammy sweat. To avoid further distressing encounters, Simon decided on this, his fourth day in Santorini, to go to the market and buy a bit of fish to cook at home for his lunch. He would rest for an hour, write more postcards to his daughter and friends, then spend the afternoon studying for tomorrow’s lesson, the subject of which was Aristophanes.

On his way to the fish stall, Simon whose mind was still on Aristophanes spotted a deal table covered in a mountain of cuddly toys, the most prominent of which happened to be a life-like green frog with an enticing grin. For obvious reasons, it brought back Simon’s grandson, Dmitri, now four months-old, for whom he decided to buy it as a present. As he was handing the money to the lady vendor, Simon caught sight of a young blond woman standing at a potted plant stall a little further down the street. He remembered her well from a dissidents’ gathering two years before. A music producer, he had found her at the same time interesting and friendly, but for the life of him could not remember her name. She was accompanied by a tiny brunette who, though pretty and lively-looking, seemed to suffer from dwarfism. The little creature, whom Simon judged extremely lovely, had a skye-terrier on a lead.

Just as Simon recalled that the young blond lady’s name was Tilly, she turned round and upon beholding him waved and smiled.

“Simon!” she called, making her way through the crowd to the toy stall.

“Tilly!” echoed Simon.

“We met at the Alexander Solzhenitsyn dissidents’ campsite picnic the Summer before last,” said Tilly.

“Caddie, meet Simon. He’s one of ours and lives at the Andrei Sakharov campsite in Devon. Simon, this is my friend Caddie; and this is Dougal,” she said patting the skye-terrier.

“A pleasure to meet you, Caddie,” said Simon, shaking the little thing’s hand warmly. “Are you two on holidays here?” he inquired.

“No, we live here now,” said Tilly. “Have you had lunch yet, Simon?”

“No, I was about to buy fish to cook at home.”

“In this case, come to my place,” offered Tilly. “We’ll eat, drink and catch up. Caddie and I are neighbours as well as friends.”

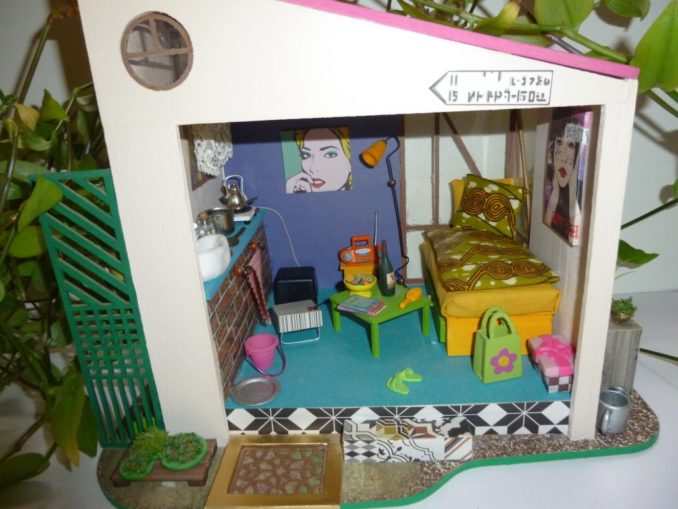

Tilly’s house was small and cosy, in two parts, one modern, the other traditional. She had adopted a stray ginger cat whom Dougal, Caddie’s dog, loved passionately. Tilly and Caddie had met two years before at the very same market and been fast friends since. Caddie was a flower gardener.

Simon, Tilly and Caddie sat around a tile-covered table to eat salad, black olives, feta cheese and bread. Tilly brought a bottle of ouzo, which they drank mixed with water from the courtyard well. When coffee, fruit and pastries arrived serious conversation began.

“The Globo-Cult has become so tyrannical,” explained Tilly, “I had to turn down the best songs because the lyrics deviated slightly from their psychotic dogma. For the whole of my last year in England I was reduced to producing complete drivel which sounded like parodies of Graun articles. It was that sad. So I decided to move here.”

“It’s the same with flower shows,” said Caddie. “Flower growing is now deemed racist and you can’t even show certain flowers because they’re apparently tied to slavery. In the end, either you remove yourself physically and mentally from that madness, or you obey their aberrant rules, which keep changing without rhyme or reason anyway. Something is allowed one day, you risk persecution the next, and so on…”

“Dissidents’ accommodation was created in order to insulate us from that very madness and last Winter the campsites managed to snatch autonomous zone status from the government. Although many dissidents work outside, they tend to be employed by dissident businesses. Little by little, we’re getting our country back.”

For the rest of his Santorini sojourn, Simon saw Tilly and Caddie every day. Tilly had a big collection of vinyls to which they listened as they talked. Simon told them about life in the Andrei Sakharov campsite, about his work running the pub with his friend Roger, about his daughter Sonya, her husband Rodion and his grandson Dmitri who lived in the Aleksander Zinoviev building in Exeter. He showed his friends photographs of Dmitri.

“He doesn’t have his mother’s copper hair unfortunately, but I’m glad he inherited her cornflower blue eyes.”

“He does look like you, doesn’t he?” said Caddie.

“Do you think so?” asked Simon. “Sonya and Rodion love their garret flat and were reluctant to leave the Andrei Zinoviev Builiding. Then, by a stroke of luck, the garret next door became vacant. They just had to have a door built between the two and now Dmitri has his own bedroom.

“I babysit two days a week so that Sonya can go out to work. Rodion doesn’t make much so any extra helps. I love spending time with Dmitri, watching him change. I was in prison all the time Sonya was growing up. Only now do I realise how much I missed out and hate myself even more for it.”

Since his daughter’s wedding, Simon had been coming to Greece twice a year to learn Ancient Greek and had always enjoyed himself, but thanks to meeting Tilly and Caddie that one visit turned out to be the best and most treasured.

In those days, the Prime Sinister of the Erstwhile Great Britain was a lazy, careless and depraved blithering idiot called Borzoi Fatturd who always appeared flanked by his two favourite foetid fools, Slowitted and Shot-Liberty Valance. Borzoi, known to some as The Eton Mess, was a third cousin of Merdoan the despot of Turdey.

Day in, day out Slowitted and Shot-Liberty Valance, both evil dwarves, whispered poison into Borzoi’s greasy ear on whom they seemed to have some kind of hold. It was known that Borzoi bragged about having bedded two-thousand women before he was fourteen years-old, which sounds surreal to this author since he was an ugly albino berk and stranger to barbers. He also had a rather disquieting habit of taking a poisonous powder into his pimply nose. His current consort was a green witch called Scary. As if all I have already recounted was not horrible enough, during the last year Borzoi had become a criminal against humanity whom Pol-Pot would have envied.

Borzoi’s Minister For Peddling Lies was a grey cadaver called Pat Badcock. Badcock had been slowly rotting away ever since he left his mother’s womb and was endowed with the reverse Midas touch: everything he came near withered and died. His mission (which he had decided to accept even before he listened to the self-destructing tape) was to devise new forms of torture to punish the British people for leaving the Wagnerian Onion a few years before. And Badcock was pretty good at that, had to be since he was good at nothing else. He went to bed at night and dreamed of the day when nothing but ruins would be left and the people he so loathed would be reduced to scratching the ground in order to find worms to eat. The truth is that Borzoi, Badcock, Slowitted and Shot-Liberty Valance belonged to a morbid elite way past its sell-by date which projected its own inevitable death on to us all.

Four days before Simon Marmeladov was due to fly back to England, Badcock the cadaver had a marvellous torture dream and upon waking up announced that all holidaymakers would have to quarantine in designated hotels for fourteen days upon their return.

Simon, Tilly and Caddie were eating a fish lunch cooked by himself at his tiny rental house when they heard the news on the radio. Simon’s face drained of all colour, his throat lost the ability to swallow, he choked on the mouthful he had been chewing, tears ran down his cheeks and he started coughing painfully. He recovered somewhat after Tilly had patted him on the back for a few minutes and made him drink two glasses of water.

“I’m to be Roger’s best man!” he had last managed to croak. “Even if I left today, I’d never manage to get there on time.”

“Roger the publican is getting married!” exclaimed Caddie. “You never told us.”

“We’d so much to talk about, I forgot,” apologised Simon. “He’s marrying Galta the dissident sculptress in seven days’ time.”

“I’ve heard of Galta,” said Tilly. “What wonderful news!”

“What am I going to do?” wailed Simon, taking his head in both hands and rocking back and forth. “At least one hundred dissident guests have been invited. I can’t let Roger down.”

“Write him a letter today,” advised Tilly. “The post doesn’t leave until six o’clock. They normally take only four days, he’ll get it even before you reach England.”

“Tilly’s right,” said Caddie. “Don’t phone or write an email, that might be intercepted.”

“I don’t own a mobile phone and couldn’t use a computer to save my life,” laughed Simon.

After Tilly and Caddie had left, Simon wrote a long, detailed letter to Roger and for good measure an even longer one to his daughter and son in-law. As soon as he had sealed the envelopes, he walked to the post-office, double stamped his letters and gave them to the post-master personally. The post-master, a quiet, kindly man whom Simon suspected of holding dissident opinions, promised they would be on their way to England before sundown.

The week had been quite hot, so on the following evening Simon, Tilly and Caddie took a picnic basket to the hills. Simon who had felt gloomy all day started relishing his friends’ company and the magnificent sunset over the harbour.

“Greece is paradise,” he said, “so much beauty all around. So is England. And yet the putrid elites won’t let us enjoy them.”

“It’s almost as if they were satanic,” mused Caddie.

“Or simply evil like all spoilt brats brought up to believe they’re God,” said Tilly. “They’ve been given so much they’ve grown unable to enjoy anything and need ever increasing stimulation just to feel something. Then they envy and hate us when we’re happy watching a sunset and having a picnic with friends.”

“Killjoys fill me with both disgust and sorrow,” said Simon. “I can’t tell which of the two emotions is stronger.”

Three days later, Tilly and Caddie saw Simon to his plane, and I must say that it was with a heavy heart that they finally parted.

In previous years, Simon who no longer liked London had always taken the train to Barnstaple directly after landing at Gatwick. But that time, immediately after passport control, he was herded on to a bus with thirty other dazed passengers and driven to a quarantine, or rather prison, hotel near the airport. The whole ghastly process took place in total silence broken only once by a brutal police officer (or foreign mercenary) who ordered them to wear two masks instead of one.

When they reached the hotel, a huge white monolith at least ten storeys high, their passport was confiscated and each man or woman was taken to his or her single room. Couples were separated and told not to mix, or risk ten years’ imprisonment. Setting foot out of the room was forbidden; food would be brought up three times a day. In between, there were tea and coffee-making facilities in the room.

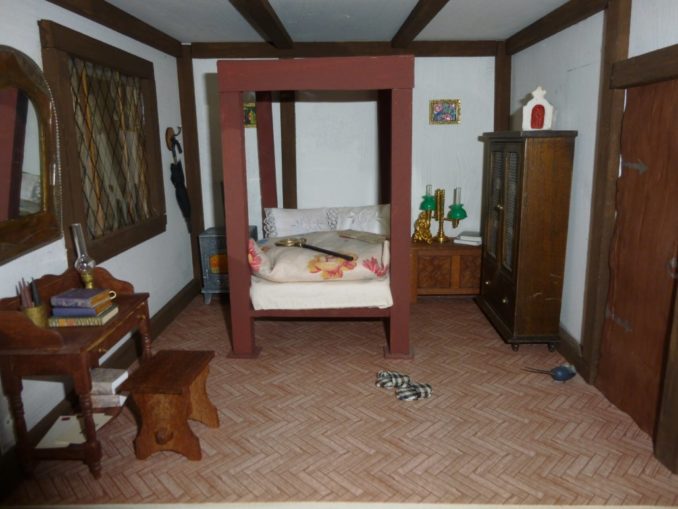

Simon sat on the bed and looked around. The room was not bad. Simon had known worse prison cells. The TV was useless to him who never watched it. He presumed the bar-fridge was full of miniature liquor bottles. Since giving up drinking three years before, Simon had only had the odd beer with friends and never got drunk. He was not prepared to give in to a tyrannical government and become an alcoholic again.

He got off the bed. The sky outside the window was overcast, the view bleak. He went to the bathroom to wash his hands and noticed at least four paranoid warning signs on the walls against slipping on the bath mat or scalding oneself. As he was drying his hands, it occurred to Simon that this was the only time he had been in prison and completely innocent.

“All taken in, prison was better,” he told himself. “At least you were allowed to work and meet other inmates. This is solitary confinement with comfort.”

Simon decided to read Aristotle until dinner was brought, if it was brought at all. You never knew with sadists. He slept poorly that night, awaking every hour or so, close to tears. He missed his daughter, grandson and son in-law.

“Babies change so quickly,” he thought, “I’ll have a hard time recognising Dmitri.”

He missed the campsite, his timbered room at the pub, and above all his friends, all of them, the ones in Devon as much as Tilly and Caddie in Greece.

“For crying out loud,I even miss my daughter’s dog!” he exclaimed, finally giving up on sleep and getting out of bed.

The morning passed slowly. Simon forced himself to read, feeling his concentration slip away when in what now felt like another life he had had to tear himself violently from Greek authors. Although he had showered, he had not bothered with a shave, there was no one to see him. So after lunch he decided to do it just to keep busy. As he distractedly listened to BBC nonsense on the radio set in the bathroom wall, he recalled how Dmitri liked rubbing his tiny hands on his grandfather’s bristly cheeks and laugh. A violent sob rose in his chest and nearly choked him.

When Simon came out nothing looked out of the ordinary. Then, putting his suitcase on the bed in order to take another book out, his eyes fell on a sheet of A4 white paper neatly laid on his pillow.

“I didn’t hear anyone coming in. What fresh hell can this be?” he wondered as he picked it up.

“Your room door and the one downstairs at the back will be left open at ten tonight. Take only what you need. A black car will be waiting for you at the kerb,” it read.

Simon did not waste time wondering whether this might be a trap. It was his one and only chance of escape and he was the sort of man who would take it. He sorted through his luggage and filled a shopping bag with Greek books and the gifts he had bought for family and friends.

“When I came out of prison three years ago,” he thought, “I had nobody; and now look at this big bag of presies for everyone I love, an art calendar for Rosie and Gideon, a book of postcards for Dasia who collects them, a framed picture for Lucy Cohen and her husband who’s my namesake, a mug for Ida to drink gin in, wedding presents for Galta and Roger and lots and lots of thingies for Sonya, Rodion and Dmitri. There’s something about that frog I bought at the market; it seems to bring good luck.”

It took Simon no more than three minutes to slip out of the hotel. No one saw him. The corridors were empty, the whole building eerily silent. As promised a black car was waiting, its engine idling. A dark, muscular man was at the wheel. He drove off as soon as our friend was safely in.

Simon asked no questions and the driver offered no explanation. He drove to a modern building about twenty-five minutes away and delivered Simon into the hands of what appeared to be a clergyman. When he was shown into a library displaying a huge Israeli flag on the wall, Simon realised that he was in fact in a synagogue and therefore the gentleman must be a rabbi.

“You can rest here,” said the rabbi, “the bathroom is through that door at the back. I have to leave you now.”

“I’ve been abducted by Israelis,” thought Simon, “and now I’m being held hostage in a synagogue!”

“It could be worse,” a voice inside his head chided. “You could have been abducted by Muslims and be held hostage in a mosque.”

For the first time in days, Simon burst out laughing.

“As soon as I get home, I’ll write a long letter to Tilly and Caddie. They’ll love this!”

Simon examined the books on the shelves along the walls. They were all in Hebrew, so would not help pass the time. A colourful tome which turned out to be a children’s Hebrew alphabet sat on one of the tables. As pencils and paper were also provided, Simon sat on one of the benches and started teaching himself the Hebrew letters. He was in fact rather enjoying himself when, about an hour later, the rabbi returned followed by another man. They both smiled indulgently when they beheld their guest painstakingly tracing letters on a piece of paper.

The newcomer shook Simon’s hand and introduced himself as Yair. He was young, or at least looked that way, of medium height, stocky with coarse black hair and bright blue eyes.

“Let’s get going,” he said in strong accented English.

Again the car was black although it was a different one this time. They drove out of London and, Simon noticed with relief, headed West. Yair was not any more loquacious than his previous driver, but for some uncanny reason, Simon felt that this was a man one could trust, who somehow exuded solidity and stability. The night-time motorway traffic was light so they rode smoothly for nearly three hours until Yair turned into a service area.

“Do we need petrol?” asked Simon with more alarm in his voice than he actually felt.

“No,” replied Yair. “You and I part company here.”

He parked the car alongside a red vintage Mini. A small brown dog Simon would have recognised in a thousand sat on the front passenger seat. As soon as he caught sight of Simon he stood at the window and started wagging his tail madly. It was then that Dasia appeared seemingly out of nowhere.

“Get in, Si,” she said. “Put your bag on the backseat and take Pavlov on your lap.”

The Israeli hugged Dasia and gazed at her adoringly long after they had driven off.

“Your friend Yair seems pretty smitten with you, Dasia,” said Simon cheerfully.

“Does he?” asked Dasia genuinely surprised. “I never noticed.”

“I thought we’d agreed we’d only involve your Israeli contacts in case of emergency,” said Simon.

“What do you call a dissident being put in solitary confinement by a tyrannical regime?” retorted Dasia. “Besides, Roger and Galta’s wedding is the day after tomorrow. I don’t like dissidents’ weddings being held up by despots.”

“May I ask who called you?” said Simon with a smirk.

“Everyone called me,” answered Dasia. “Even Ida called me. She got in a right state when Roger told her about your letter. In fact, the whole campsite was in a state.”

“Have you been in touch with Sonya?” inquired Simon anxiously.

“She’s at the campsite with her family,” answered Dasia. “They’re all waiting for you.”

“What about Cesariot?” asked Simon. “Did they leave him behind in Exeter?”

“No,” said Dasia, “they brought him with them. Rosie and Ida are fitting all canine wedding guests with black ties this afternoon. After we get to the campsite, I’ll have to prepare Pavlov psychologically.”

As my beloved readers probably remember from previous instalments, Dasia was not a big conversationalist, so Simon dozed the rest of the way. When he opened his eyes the tall, white Andrei Sakharov campsite gate was in sight. As Dasia stopped the car in front, Sonya and Roger burst out to greet them.

“We made it, Dasia!” shouted Simon before jumping out.

“We were always going to make it,” replied Dasia. “We have right on our side.”

© text & images Doxie 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player