I still scan comments on an article recently published because I enjoy the opportunity to have a dynamic exchange with folk of widely varying knowledge of the sea in a much less time-consuming way than would be required if responding to them individually. Comments on Part 8 were no exception so here goes.

I like precision combined with brevity but don’t always have time to achieve that myself. “Chimp Monkey” seems to have mastered the art and I humbly thank him for getting me to “Heave-to” over my misuse of the word “Hoist”.

I also hope he will develop his idea of writing an article or series about the incorporation in ordinary speech of Naval sayings. I’ve come across a few myself like “A good square meal” but would be delighted to read a more comprehensive treatment of the subject.

I also found interesting his remarks about the use of electrical power for maritime propulsion. I suspect the same drawbacks will become apparent in a similar way over its use in road transport, despite the Government policy of enforcing its introduction due to claimed environmental benefits. Unless of course there’s a real breakthrough in electrical generation and battery technology that’s not dependent on the exploitation of children mining “rare earth” minerals in remote places.

I enthusiastically endorse DJ’s remark that Greenwich Observatory is a fascinating place to visit, and not only for the Harrison Rooms display.

“Cephalopod” rightly draws attention to the dangers of the sea near Ushant – tidal currents there can reach 8-9 knots or more and that means a small yacht such as mine would be moving backwards in space whilst going at maximum speed through the water – or alternatively at more then twice its normal forward speed if the current is carrying it along – such behaviour close to rocks presents very serious problems normally solved by transiting the area at slack water. I may illustrate this in later articles with examples of places where I had to be very careful for this reason.

I must also answer “Cromwell’s Unmentionables” question about the use of degrees, minutes and seconds instead of a decimal notation. A nautical mile is defined as “the distance on the earth’s surface subtended by one minute of latitude along any line of longitude”. All standard British Admiralty Charts and equivalent US ones used that notation and Marine, Air and Space ones still do. (Incidentally, the speed unit of knots is a rate of one nautical mile/hour and if Chimp Monkey gets round to writing his article(s) perhaps he will tell us the very practical reason the word “knot” was used).

Decimal presentation is a relatively recent innovation introduced as electronic computers were developed – for example, Google Maps didn’t really get going until the early 2,000’s but if you use it these days by right clicking and look at the position revealed you will see it is in a decimal form with 5 digits behind the decimal point. In the adjectival notation 0 degrees, 0 minutes, 1 second is easier for the human brain to cope with than .00027.7 recurring degrees. That may be why the traditional notation is still in use.

GOING FOREIGN

I have been vividly reminded of the exhilaration I experienced during the next couple of months when leafing through my log sheets for July and August. I spent nearly all that period using Falmouth as a base and going off sailing with anyone and everyone who would come with me – family, colleagues from my last days at work, people met at sailing school, people who had advertised their services as crew in the yachting press, and so on. I went up the coast and down from Falmouth to Fowey and Helford, back to the Scilly Isles as my own skipper and navigator with one other companion, and to Plymouth and back to extend my range and experience of England’s south western coast.

But two voyages stand out from the rest because they were respectively across the Celtic Sea to Southern Ireland and the English Channel to Brittany. This article describes the first and the next will do the same for my first trip across the English Channel.

FALMOUTH TO SOUTHERN IRELAND

The new owner of the Yacht Sales and Charter business managing Pacific Seacraft’s Agency was a young man who had made enough money in what I took to be the financial services field to buy the business from its original owner. Like me he was a newcomer to sailing and as keen as I was to enjoy it as a practitioner.

Together we evolved a plan to sail Alchemi and a larger sister to Southern Ireland (a Crealock 37 built by Pacific Seacraft). The new owner had three or four permanent employees and one or two casual ones including an experienced sailor from South Africa. We had enough hands to form crews for both yachts and the South African and an employee who specialised in fibreglass and gelcoat repairs were assigned as crew on Alchemi.

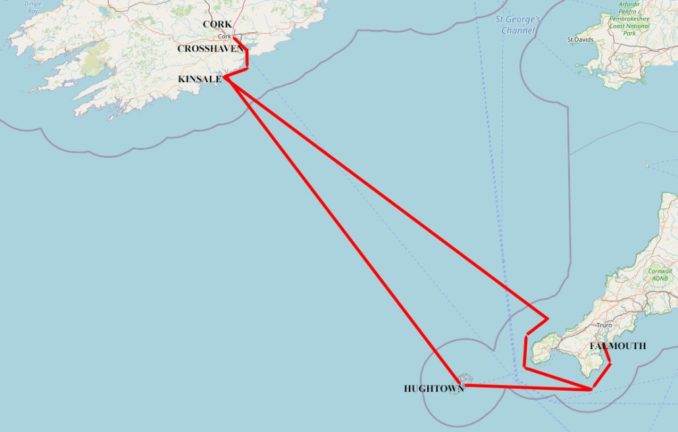

It is just under 200 nautical miles from Falmouth to Kinsale and we knew that was going to take us more than 24 hours so this was my first experience of planning a Watch System for an overnight passage on my own yacht. I had made cross-channel trips at sailing school but there had been lots of crew on those and the school’s instructors had been responsible. So the trip to Kinsale as skipper on my own yacht was a big step for me.

Looking back on it now I remember thinking each of us being on watch for three hours at a time would be about right because it nominally provides six hours for each person to rest when off duty. In practice I learned the off-duty period is nearer five hours because it takes about half an hour at each change-over to take-off or put on wet weather gear, explain the yacht’s position, what the wind and weather conditions are, whether there’s any other shipping about and so on.

In later years I also learned the quality of rest one gets depends a lot on the wind and weather – the boat is never still and in rough weather one can get thrown about a bit. It also depends on whether one is in the uphill or downhill bunk. Under sail a yacht is always heeling and the lower bunk in which one is supported by a cushion leaning against the side of the hull is always much more restful than the uphill one in which one is stopped from falling off the bunk and onto the cabin sole by an ever-moving piece of canvas called a lee-cloth. I also learned it’s a good idea to vary the watch length according to the weather rather than stick rigidly to a pre-planned time-table. The latter may be necessary in Naval circles where routine and discipline of large numbers are important but in a small private yacht its hard to maintain concentration even for three hours if the weather is rough or foggy, but easy to go on for four or five hours or even longer if the conditions are benign.

We left Falmouth about 10:00 on Sunday 21 July 1996 having made a passage plan whose objective was to arrive at Kinsale whilst it was still light the following day. That’s not quite as easy as it sounds because there is enough commercial shipping between the English Channel and Ireland to require separate traffic lanes as they pass around southern Cornwall. Furthermore there are strong tidal currents in the same area so we had to reach certain positions at prescribed times as well as avoid big ships in narrow shipping lanes off a rocky coast. In a yacht moving at 5-6 knots through the water, the distance over the ground gained with a favourable 3 knot current over a typical 6 hour cycle is as much as 18 miles, and of course the same distance can be lost if the current is adverse. So there is potentially a 36 miles, or 6-7 hour difference in passage time between catching the current at just the right or just the wrong time. On long ocean passages that doesn’t matter very much but on short coastal ones it can make all the difference between arriving at a strange harbour in daylight or in the dark.

On this occasion there was enough wind to sail but not enough to push us along at the speed needed so we had to motor-sail for rather a long time until we were round Land’s End and headed out across the Celtic Sea. There was more of a breeze, between 10 and 15 knots, on Monday so we had a better sail and arrived at Kinsale soon after 4 pm.

Kinsale is an attractive small town about three miles inland up the river Bandon from the open sea, first established as a walled town in the 13th century when it was owned by the Anglo-Norman De Courcis family. It has a long history of involvement with Irish resistance against first the Norman’s and later the English. The Battle of Kinsale in 1601 became particularly famous, or notorious depending on one’s point of view. In that year a Spanish Armada hoping to make landfall elsewhere at the request of Irish leaders in Limerick and Galway, was driven into the harbour by bad weather and occupied the town.

That resulted in a swift response from Elizabethan England that only 13 years before had fought off the better known Armada sent up the English Channel to support an invasion by a Spanish army quartered in Flanders. Elizabeth I’s representative in Ireland, Lord Deputy Mountjoy, swiftly besieged the Spanish in Kinsale but was attacked from the north by the Irish and their forces. He eventually succeeded against all his adversaries and Kinsale remained under English rule.

This result was an historic turning point in Irish History and Spanish expansionism. The Spanish had failed to invade English Territory for a second time, and in their effort to win support from other European countries. The Pope paid lip service to Spanish ambitions but withheld real help for fear of offending France by supporting the Habsburg Royal Family who were already dominant in Spain, Portugal, Austria and the Southern Netherlands. The Irish had failed to expel the English and would not succeed in doing so for the next 321 years. Kinsale once again became a small Irish fishing town and nowadays tourism is an important industry. The town prides itself on being called the Gastronomic Capital of Eire. We certainly enjoyed a fine dinner in one of its many restaurants.

Before resuming the tale of my voyage I’d like to mention one more historic fact about Kinsale that I found interesting.

Sir William Penn was a naval adventurer who became an Admiral in Cromwell’s navy and fought for the Commonwealth in Southern Ireland but was later appointed Governor of Kinsale by Charles II after restoration of the Monarchy. He owned estates in Ireland and at one stage sent his son, also named William, to manage them. After his father’s death, the younger William accepted a large Land Grant in North America in settlement of debts Charles had owed his father for support during the Restoration. This William Penn was a Quaker and became famous as the founder of the State of Pennsylvania (Penn’s Woods) as a region where fellow Quakers could follow their religion without persecution. Thus Kinsale played an important part in the long-standing history of Irish antagonism towards the English and the development of Eire’s present day links with both American and European countries and their rulers.

Kinsale Harbour lies about 2 miles inland from the mouth of the river Bandon and is well protected from the wind and waves of the open sea.

The town has a great character with many winding streets containing colourful buildings.

We had a great sail after leaving the town with a 20 knot breeze over a calm sea and averaged a speed of 8 knots – well above Alchemi’s nominal hull speed of 6.4 knots. That took us up the narrow channels into Lough Mahon and on to Cork. It seemed very strange to tie up to a wharf in the very centre of a busy city. We didn’t stay long though and went back to stay overnight at the Royal Cork Yacht Club in Crosshaven that claims to be the oldest in the world having been founded in 1720 by the great grandson of one of Charles II’s courtiers. It is a political curiosity that Irish people are still proud of some of their historic associations with the English as exemplified by continued use of the prefix Royal in their Yacht Club names – Royal Cork (William IV in 1831), Royal Irish (Queen Victoria in 1846) and the Royal St George (Queen Victoria in1847) with the last two both being located in Dun Laoghaire Harbour in Dublin Bay.

We returned to Falmouth via Hugh Town on St Mary’s but I won’t go into any detail about that having already described our visit there in the article about Alchemi’s maiden voyage.

ANOTHER OUT OF SEQUENCE YARN

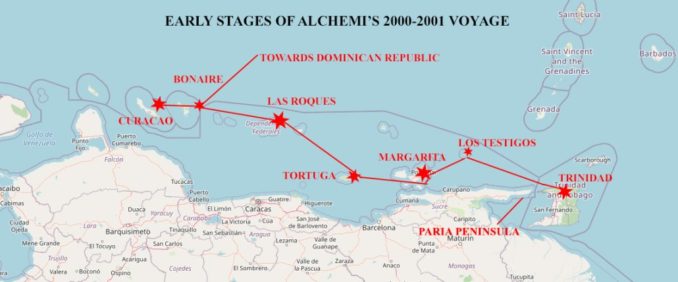

Alchemi crossed the Atlantic from Tenerife to Guadeloupe in 1999 and was left in Chaguaramas, Trinidad, during the hurricane season between April and November 2000. My plan for the rest of 2000 and early 2001 was to sail parallel to the Venezuelan coast through the offshore islands and then to Bonaire and Curacao in the Dutch Antilles before going north across the Caribbean to the Dominican Republic and beyond.

This yarn stems from one incident in the early stages of that year’s voyage.

In 2,000 and for a few years after, Venezuela had not degenerated into the “problem state” it has since become but was notorious amongst yachties for casual violence and piracy along the northern shore of the Paria Peninsula opposite Trinidad. For that reason a Swedish sailor and I had agreed we would like to accompany one another and maintain VHF contact as we progressed. The Americans call this a “Buddy Boat” arrangement and it worked well for us – we had no security problems, several enjoyable evenings with other Scandinavian sailors, including a very memorable Christmas Eve in Bonaire, and Peter and I are still friends. We passed as far north of the Paria Peninsula as possible whilst maintaining course to a small group of islands called Los Testigos whence we continued with many an adventure until arriving at Bonaire where there was a crew change on Alchemi and then on to Curacao before returning to Bonaire and heading across the Caribbean.

There is a deep inlet on Curacao’s south-western shore leading to a shallow inland lake called Spanish Water. There’s a photo of it below taken in 2011. In 2001 there were far fewer buildings but on one shore there was a Bar-Restaurant that also provided services to yachts anchored in the bay. This type of business was quite common in South America at the time because the yachties brought in very welcome foreign exchange supplementing income from locals and required very little extra capital – a short pontoon to which dinghies could be tied, a shower or two, and a weekly shopping trip to the local supermarket was all that was needed. There was one such in Spanish Water going by the upmarket sounding name of Sarifundy’s marina, near the centre of this 2011 photo. I passed through again in 2009 after completing a circumnavigation and Sarifundy’s was still there then.

Here is an account I wrote about my first visit.

At about nine in the morning Alex and I rowed off to Sarifundy’s marina in the dinghy to have a shower and so on. As we arrived I heard a man with a South African voice, accompanied by his girl-friend and a crew member, explain to Lizzie, the marina owner, that they had just arrived from Trinidad and the latest news was – “A boat with a couple on board and anchored off the Paria peninsula had been boarded by an armed gang, robbed of everything they possessed, and the boat cut adrift to float out to sea – they managed to sail her on to the beach and save themselves”. This was so similar to a story I heard before that I thought it must be the incident first reported in May and asked “When did this happen?”

In a rather off-hand voice the South African replied “Last week” and then asked “Do you come from Cape Town?” Naturally I said “no” and he then said “You must have a brother there then”. Again I said “No” and his girl friend chipped in with the remark “You certainly have a double there then”.

The South African’s next question was “Do you have a boat called Alchemi?” Quite taken aback by his knowledge I confirmed that was indeed the case whereupon he said “I sailed with you from Falmouth to Kinsale in 1996.” This was the same man and our meeting again was one of those fantastic co-incidences that only happen very occasionally. He, with his girl-friend and crew member were sailing a yacht on a “Delivery Contract” from Cape Town to San Diego in California and had put-in to Spanish Water to rest for one night only!

To be continued………………

© Ancient Mariner 2021

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file