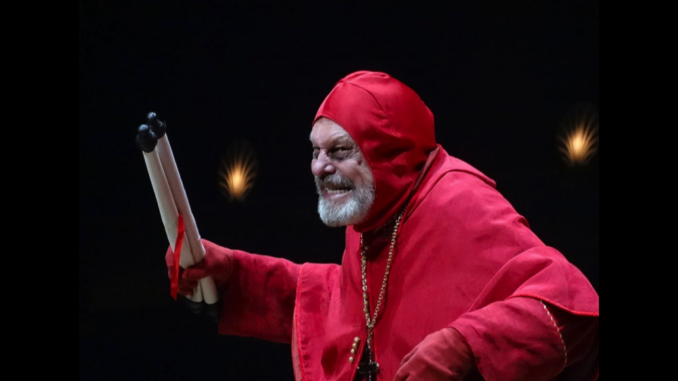

Photo 02-07-14 12 47 50, Eduardo Unda-Sanzana – Licence CC BY-SA 2.0

Twelve Monkeys (1995) is Terry Gilliam’s love child. Perhaps one of the industry’s most awkward talents, Gilliam has directed some of the most unique and compelling films of the last twenty years. He may be remembered first for Monty Python & the Holy Grail, The Fisher King, or even Fear & Loathing in Las Vegas — but the cynical, off-center, science fiction-laced atmospheres of Brazil and Twelve Monkeys are perhaps his most ambitious of all.

The latter is one of his most accessible films, but I still wouldn’t blame first-time viewers for feeling lost: this is, after all, a loopy time-travel adventure told from the perspective of a (possibly) unreliable narrator. Nonetheless, it shares top honors with Brazil as being Gilliam’s most rewarding production. Featuring a terrific cast, an engaging plot, and enough mind-bending moments to warrant multiple viewings, Twelve Monkeys has a little something for everyone and still holds up 25 years after its first release. It is a masterful work of dystopian science fiction, with a highly imaginative plot, a tight and literate script, fantastic steampunkish sets and props.

The lead performances are remarkable. Bruce Willis turns in one of the best performances of his career, compelling as a man who is heroic despite all his doubts, fears, and failings. So too does Brad Pitt (who’d just come off another terrific performance in Se7en). But Madeline Stowe steals the film. She not only has great chemistry with Willis, but walks the delicate line of gradual insanity quite well. Did I mention I would? The ultimate mystery of exactly who Cole’s up against also works to the film’s advantage: a villain isn’t fully revealed until its final minutes, and (there’s more than one) if you’re paying close attention. But these characters are just the tip of the iceberg: 12 Monkeys offers a dense atmosphere in addition to other strengths and, as a whole, is one of those films that feels like more than the sum of its parts.

To divulge the entire plot and pathway of 12 Monkeys would ruin the experience for those new to the film — and besides, it probably couldn’t be done very well in less than 1,000 words. Here’s something to get you started: we’re put inside the life of one James Cole (Bruce Willis), a prisoner from the mid-21st century who “volunteers” to return to 1996 and find out how a mysterious virus wiped out practically the whole human race in 1997. The survivors live underground, in totalitarian lockdown, under a Permanent Emergency Code, ruled by a politburo of scientists, a whole committee of Dr. Strangeloves. In 2035, the scientists somehow invent a way to travel back in time. They wish to send someone to the past, just before the outbreak of the plague, in order to . . . No, they don’t want to prevent it. If the plague never happened, none of them would be ruling over the pitiful remnants of the human race. Instead, they simply want a pure sample of the virus, before it mutated. Their motives are never made clear. Is it for pure research?………. Would an earlier strain of the virus allow them to create a cure ?………………Would (Maddy Stowe ???, yes)

The problem is, Cole’s mistakenly sent to 1990, where no-one believes his story & he ends up being incarcerated in a mental institution – because that’s what one does with people who claim to have come from the future to prevent the human race from dying in a pandemic. There Cole meets up with the stuttering, mildly psychotic, mental patient Jeffrey Goines (Brad Pitt), a radical environmentalist and animal rights advocate, who may or may not be involved with The Army of the Twelve Monkeys, a group supposedly responsible for the virus. Along the way, he also meets the empathetic Dr. Kathryn Railly (Madeleine Stowe), who turns out to be Goines’ ex-psychiatrist and one of Cole’s only real supporters. Cole tries to escape to complete his mission, but he is captured and locked in a cell, from which he mysteriously disappears. Apparently, the scientists have put implants in his molars that allow them to pull him back into the future, where he is debriefed and then returned to the past, first ending up in the trenches of WWI, where he is shot in the leg, then finally ending up in 1996.

Six years after her encounter with Cole, Dr. Railly has published a book on the “Cassandra complex”: people like Cole who warn society of impending disasters but are not heeded. After Railly gives a lecture on her book and signs copies, Cole kidnaps her. He needs her help. He now believes that the virus will be released by Jeffrey Goines and a radical environmentalist group called the Army of the Twelve Monkeys. Cole is afraid that during their time in the mental hospital, he actually gave Goines the idea of wiping out the human race with a plague. (If you are going to construct stories around time travel, you might as well milk it for every paradox.) Railly, of course, is terrified. But she does not go to pieces. She’s a doctor. She tries to understand Cole and convince him to let her go as he drags her through his quest for the origin of the virus. Philadelphia in 1996 turns out to be almost as dystopian as Philadelphia in 2035. After some harrowing misadventures, with Railly, Cole is pulled back into the future. When the two are apart, a delightful role reversal takes place. Railly comes to believe Cole is not a madman. He really is from the future. Cole, however, comes to think that he’s actually mad. He does hear a mysterious voice that is never explained. The scientists also, frankly, act a bit crazy. And really, doesn’t the whole story sound a bit insane?

When Cole is returned to the past, he seeks out Railly because he wants her to cure him, only to discover that she has taken up his mission with the manic intensity of a true believer. You laugh when you see it, but the real delight comes in retrospect, when you see that it was completely inevitable. After Cole and Railly get back on the same page, they go after the Army of the Twelve Monkeys, only to find . . . Well, I’m not going to say any more about the plot, save that there are many more twists and turns for you to enjoy.

Although time-travel films and psychological thrillers have grown in stature and complexity during the last two decades, 12 Monkeys felt extremely unique at the time and has outlasted most films in both genres. Different time periods are touched upon — from cluttered, disorienting future landscapes to the chaotic events of World War I — and Cole gets the privilege of being our confused, almost feral tour guide from finish to start. Naturally, he doesn’t know who to believe or trust and often acts out of sheer survival instinct. The “mental divergence” he suffers from (represented by a raspy voice and later personified by a homeless man in one of the time periods) is with him nearly every step of the way, scolding him for each mistake. It’s one head trip after another…and to make matters worse, Cole’s dreams might actually come true. Everything comes full circle, like it or not, and history is doomed to repeat itself. Or is it?

Twelve Monkeys isn’t a “deep” film. It doesn’t invite us to ponder philosophical or theological issues. It doesn’t seem to be an allegory for anything else. It doesn’t need to be. The world it creates and the story it tells are highly satisfying in themselves: by turns surreal, terrifying, funny, and moving. It is also visually striking from start to finish, with imaginative sets, beautifully constructed shots, and a gauzy glamour that bring to mind Hitchcock. (One of the settings is a Hitchcock film festival.) Set within a materialistic, scifi universe, what you see is almost never what you get, because madness and false memories systematically estrange us from reality. Gilliam methodically mirrors events in the “real world” with movies, television shows, and commercials, placing us all in the world experienced by madmen, who see portents, intelligible patterns, and hidden intentions where sane people see only chaos and coincidence. BaPH would have been at home amongst the script writers. Twelve Monkeys is also mercifully free of political correctness. (Particularly when Cole calls a wrong number in 1990.) In fact, I can’t think of a single false note in the entire film, not even the music. I was not expecting the Buckmaster score, which riffs off Astor Piazzolia’s Argentine tango music. But it works.

Even though Twelve Monkeys was released in 1995, it seems quite topical & very relevant in the age of Corona Chan. So if you are looking for more than just boxset viewing, I highly recommend it. It is a depressing vision of the future, but it will make you feel lucky. James Cole had a lot more to complain about than we do, and he bore it far more admirably.

© DJM 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player