THURSDAY

Alan Dare watched Mohammed Badr wake slowly from his drugged stupor; the man must be dying of thirst, he thought. They were in a large barn, bare and devoid of content other than some animal stalls, all occupied except for the one in which Badr was bound and chained. A door was ajar, letting in some of the limp early morning light, joining that which filtered through the dirty high-level windows.

Alan knew the floor was freezing, softened only by animal litter, but could read the prisoner’s face sufficiently to see that the man’s feelings were colder than his body as he realised that he was surrounded by three men, all masked and in grey overalls. One, Art, would seem a virtual giant, another, Georgy, almost Arabic in appearance from the look of the uncovered patch around his eyes, but clearly no brother from their expression, and Alan himself, blondish haired.

“Good, you’ve re-joined us. You must have been tired; you were out for almost twenty-four hours. Let me tell you how it’s going to be. You will tell us all we want to know, every last detail without hesitation, just the truth. If you don’t, you will not survive the consequences. Clear?”

Art removed the gag in Badr’s mouth.

“I’ve rights…”

The kick slammed him into the left-hand stall. Art picked him up and lifted him over the stall and held him seemingly without effort. Badr could see the pigs, unclean pigs, in the stalls beyond. Alan sighed. “Wrong answer, I see you’ve noticed our evidence disposal team. Good. Here’s proof of our intent.”

Badr tried to scream as the fingers of his left hand were laid flat on top of the stall partition while Alan pulled out a small cleaver. Art pushed the gag into Badr’s gaping mouth, the man was shaking and trying to flail himself free until the moment white hot pain coursed through him and his appalled eyes saw Alan drop his digit into the neighbouring stall where it was welcomed with happy squeals; with that Badr slumped back into unconsciousness.

Alan stepped back. “Lord help us, I’m not sure I can take too much more of this.”

“He’s done worse to others, innocent women and children. There should be no pity, nor guilt.”

Alan looked at his companion with mixed emotion. Georgios Tredare was carrying something personal, an ancestral loathing of the Muslim Turk passed on from his Greek mother, despite his birth and upbringing in Britannia. How different from his own privileged Australian childhood, a culture without ancient hatreds. He had left aged eighteen for a year’s tour of the old world, arrived in England and never gone back. And now, some nineteen years later, life had transpired to make him a killer, a torturer, in a bleak old barn on a remote god-forsaken farm, with his wife and children blithely unaware of what he was now doing. Jesus forgive me, he thought. He couldn’t though let his companions see his lack of strength of will or courage lest they doubt him; he was already confirmed in his belief that moral courage is more precious, more easily eroded, than the physical: he felt his draining away with every second in this place of horrors. Focus, remember why, pull yourself together; the prisoner was already showing signs of stirring. He nodded to Art, the giant.

“Wake him.” A pail of icy cold water slammed the prisoner back into consciousness.

“Now Mr Badr, time is short and so is our patience and, if you continue to defy us, so will be your anatomy.”

When he came to Badr found himself trussed to a plain wooden chair, with one arm tied behind his back to the chair and the other, his left swathed in a rough cloth and tied across his chest. His mouth was free of the gag again, but he felt the presence of one man, surely the giant, behind him with a hand clasping the nape of his neck. Another, the Aussie seemingly, sat on an identical chair two yards in front of him. To his left there was a table with several metallic implements which he struggled to make out in the dim light, fainter now that the barn door was closed. The third man stood just to one side and behind his companion, directing a video camera on a tripod.

Must be some kaffir black operations team Badr thought, but even they had limits, especially as he must still be in the UK. His spirits rose, only to be dashed as the pain from his hand finally intruded into his mind. How had they traced him, who was the betrayer?

“What you have done to me? Who are you? What d’you want? Why am I here”?

“We ask the questions.”

The presumed Australian nodded to the one behind him. The agony in his neck was stunning in its speed and severity, he felt sick, faint, on the verge of collapse. The pressure was released, but he knew that it was only a second away. He was frozen, hungry, thirsty, racked with pain, and almost totally disorientated.

“We understand that this situation is familiar to you from your past in Iraq and elsewhere, only this time from the other side of the camera. Firstly, you will make a full confession of your activities in spreading terror to the innocent. If you do not, or attempt to mislead us in anyway, then each time you lie another part of you will go the way of the first, until there is nothing left to follow, am I clear?”

“I’ll never betray my holy trust to you damned crusaders. All you do is offer me welcome martyr…”

Before he could protest further the pain in his neck returned, followed by the gag. The cameraman switched off the video recorder, removed the prisoner’s right running shoe and sock and pressed the foot flat to the floor. Alan came forward holding the cleaver, just as the combined pressure on his neck and his struggle to breathe through the gag sucked him into brief unconsciousness, only to re-emerge once more into pain-wracked awareness.

Two hours later, after several more sessions, Mohammed Badr’s will to resist collapsed. Nothing in his training and experience had prepared him for this. Western agencies weren’t supposed to behave like this; they had rules, limits and weaknesses to be exploited by the certain and death seeking.

After three further hours he was done. He was allowed a little water, but remained tied and gagged. The Australian, the apparent leader, disappeared taking the camera and notes he had transcribed as they went and made for the farmhouse, saying to the others, “I’ll send a couple of guys over to replace you. We need to start following up what he’s given us. Hose him down, put him in the bunker, give him a little water but keep him wet, hungry and cold.”

Semi-conscious, Badr felt himself pulled across the barn floor into an occupied stall where the straw and litter covering had been scraped aside and a concrete hatch pulled out. Hunger, cold and loss of blood meant that he was only dimly aware of being lowered, none too gently, into a black void. The hatch above him was replaced and he could hear faint scraping as the litter and straw covering was re-laid. He lay shivering in absolute darkness as the swine shuffled about just seven feet above him. The darkness about him though was as nothing compared to the blackness within as total despair and the realisation of failure gripped him: if he could have ended it all by mere thought he would have. A last flicker of resistance ebbed away as he felt his way around his new refuge to realise there was nothing but bare concrete surrounding him and the hatch appeared to be immovable from below. Despair surged through him once more and this time there wasn’t even a spasm of resistance as he felt his chance of entering the place for martyrs fading away. He had failed. They had broken and brutalised him, treated him as he had done others. He saw for the first time the realisation of his actions, the consequences: it was as if this dark room was brightly lit and mirror-walled, there was nowhere to hide from himself, his abjection was total.

The sound of nearby soft, almost furtive, movement prompted Sally Bowson into wakefulness. Lord, her head hurt. Reflexively she tried to open her eyes, her right one she was barely able to open at all such was the pain and swelling, but the grey-blue left one’s emergence caught the attention of the source of the nearby movement in the room. In the half-light of the curtained room the shadowy figure settled down on the end of the bed by her feet. Sally realised that she was in a bed under layers of sheets, blankets and a quilt. The room appeared to be quite small, with whitewashed rough plaster walls, a simple dark wood door, and similar cupboard and chest of drawers. Her vision was still unclear, vague and surely not to be explained just by the lack of any form of internal light.

“Welcome back. How d’you feel? That’s quite a knock on the head you’ve had. By the way, my name’s Martha, Martha Penwarden.”

The voice was rich in a thick, slightly stilted West Country way, almost as if English were not her first language. She was tanned and weather-beaten in complexion, with lightish eyes, and dark, slightly greying hair tied back. Late forties perhaps? She was wearing a plain grey woollen top.

Something was nagging at the back of Sally’s mind. “Where am I, what’s happened to me?”

“You’re safe in my home, the boys found you out on the moor; you must have had a nasty fall so they brought you here. Would you like some light?”

The speaker got up from her place on the bed and went to the window, pulling back the plain blue curtains and letting in the rapidly brightening Spring morning light.

“Would you like some tea, water, something else? Tea? Ah, good, I’ll go and get some. My husband would like to have a word with you.”

As she went to the door and on to what was clearly a landing beyond Sally took in more details of her host and her surroundings. A simple rustically furnished bedroom, thick cotton sheets, plain blue quilt above, her hostess of medium height, slim, whose grey top was revealed to be a knee length jersey dress; a simple unassuming elegance combined with practical comfort and lots of pockets. The room was cool with no source of heating other than that ebbing in from the landing. She tried to sit up, but the pain in her head was reignited by the attempted movement and she retreated under the covers once more, a slumbering lethargy overcoming her despite the feeling of that nagging unarticulated question vying for her mind’s attention.

The woman who called herself Martha was speaking to someone downstairs in an unknown language, to which there came a similarly incomprehensible reply, and then the sound of footsteps climbing the stairs. Martha turned to face her, “Sorry, force of habit. My husband, Iltud, will try to answer any questions you have.”

‘Iltud, what kind of name was that, was she in Wales’?

A dark haired tall man of middle age let Martha, his apparent wife, pass on the landing and came into the room. Worn tweed trousers, grey shirt, green pull-over, he was dressed like a well-to-do but working farmer. He too was weather-beaten, obviously a man who spent most of his life outside.

“How’re you feeling? Your son is fine, and he’s sleeping. We didn’t want him to wake you. Martha trained as a nurse and while she’s cleaned and bandaged your head wound; she thinks you have concussion. We’ve sent for the doctor again just in case.”

“Where am I, what happened? I must see Josey.”

She asked the questions by instinct, but partly to mask the guilt about forgetting her son in her confusion.

“Of course you must, but it is best he sleeps. Have something to eat and drink and get looked at by the doctor while he rests.”

There was assertiveness in this man’s manner, a gentle authority. Before she could argue he went on, “You travelled further than you realise last night, a woman walking alone across the moor at night with a young child, you must have known better? What were you thinking?”

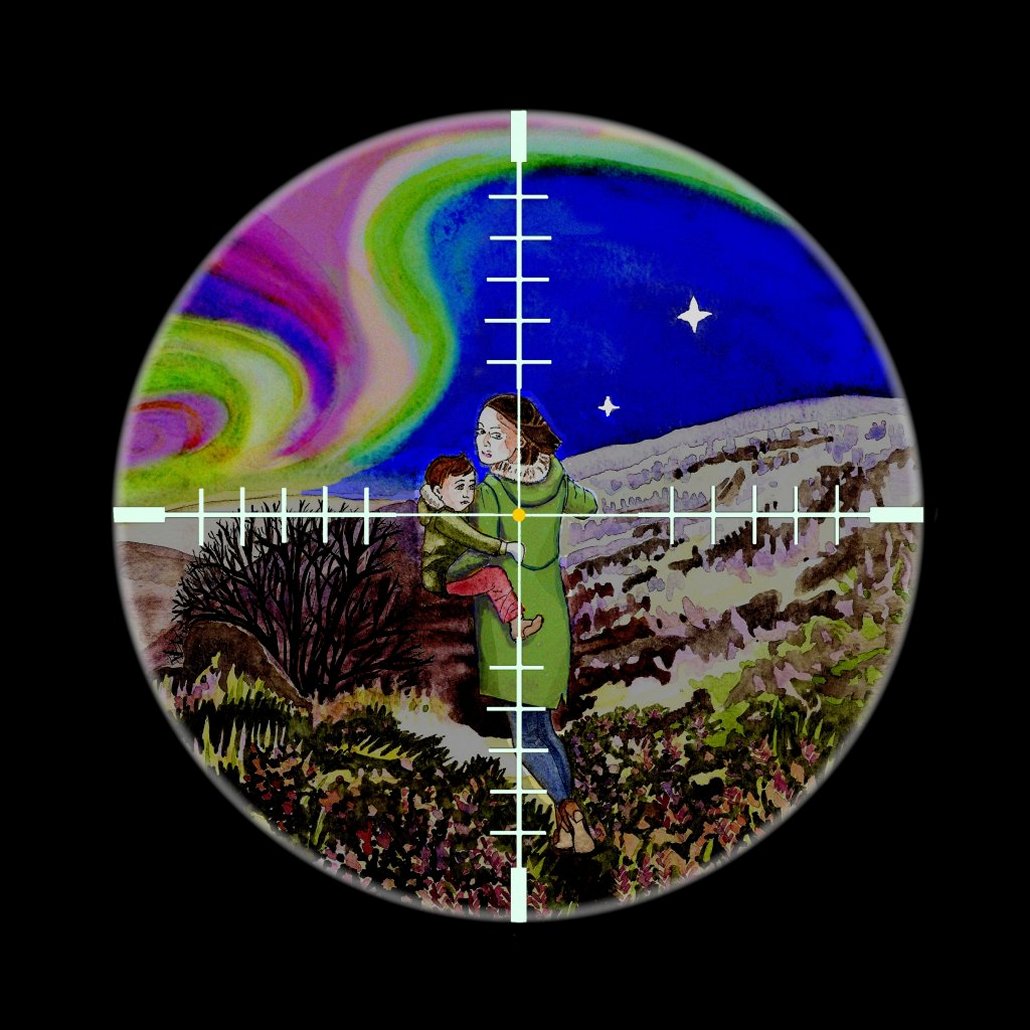

Words poured out of her in a torrent. “My car broke down, no phone signal. I grew up by the moor. What were those things chasing us? Where am I? I need to call my mum and dad, and my husband to let them know…” The panic of last night started creeping back as questions flooded her mind, “I want my son, you’ve no right…”

She hadn’t been aware of more footsteps climbing the stairs carrying another chair. Similarly dressed to Iltud except for green military style trousers and boots; a taller and younger man ducked through the low doorway, placed his chair by the window, sat down and looked at her from keen grey eyes.

Iltud cleared his throat. “This is Mark the Seigneur for this parish, of which I am Steward. After what you went through last night I don’t want to give you another shock, but we have to, our laws…”

He paused uncertainly, looking back at his younger companion, who nodded. “I’m sorry, I wish you had more time to recover, but… You’re in what we call “The Pocket” and you won’t find it on any map. I don’t know how you found your way here, but it’s not unknown for strangers to stumble upon us, runaways, the lost, those guided by greater forces if you like. However, once here you will have to make a new life with us and there are no means for you to communicate with the outside world, or to leave. You’re not our prisoner, but one ‘of the land’, as are we all.”

Her jaw dropped. She could barely register what he was saying, he was making no sense, and it must be the concussion…

© 1642again 2018