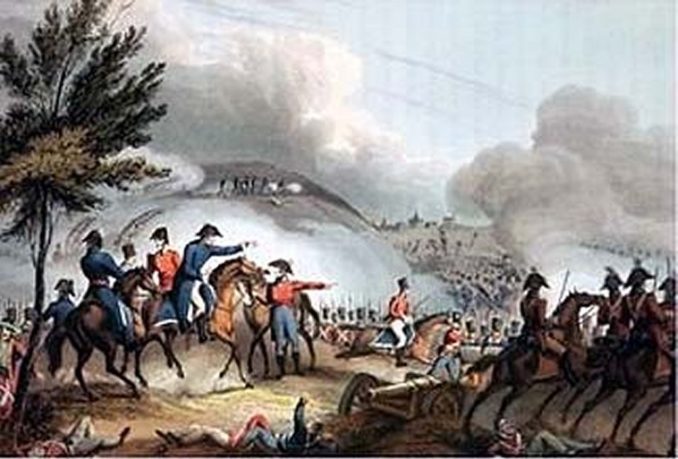

Illustration von J. Clarke, Koloriert von M. Dubourg / Public domain

As any Puffin knows, I’m a card-carrying member of the ‘First Duke of Wellington Fan Club’. No, not because of his good looks, how very dare you! He’s dead, he is, more’s the pity – he had an excellent way of dealing with the then civil servants and his temper was feared. Mind you, in the face or real danger he was genuinely unflappable. More on that below.

Since today is the anniversary of the Battle of Salamanca it’s a very good opportunity to look at the man and at what he did that day. Rest assured – I’ll not bore you with what division went where when, me not being a specialist in military matters. There’s an excellent video which does just that and which you might like to watch, but be aware that the actual battle report only starts at about 7.45 mins in.

So – it is the summer of 1812. Other events were taking place in these summer months. First and foremost is Napoleon’s invasion of Russia. He crossed the Niemen with his 600,000 Grande Armee on June 24th. We remember what happened next.

Meanwhile, at the other end of the continent, in Portugal and Spain, Wellington, created Viscount Wellington after the battle of Talavera in 1809, had made Portugal and Spain into a huge thorn in Napoleon’s flesh. The names of the French generals and marshals Wellington defeated, never mind those who actually died in those battles, read like an excerpt from Napoleon’s honours list: Junot, Marmont, Masséna, Ney, Soult … leading to the famous outburst of Napoleon at breakfast on June 18th 1815, before battle commenced at Waterloo:

“When Soult suggested that Grouchy should be recalled to join the main force, Napoleon said, “Just because you have all been beaten by Wellington, you think he’s a good general. I tell you Wellington is a bad general, the English are bad troops, and this affair is nothing more than eating breakfast” (link)

Well, we all know how that little encounter between the Duke and the Emperor ended. Napoleon had always looked down on Wellington with disrespect, labelling him ‘just a Sepoy general’. It was in India, as Sepoy general, that Wellington learned the lessons he applied throughout the Peninsular war.

There’s another huge miscalculation made not just by Napoleon but also by his generals in Spain, especially by Marmont who faced him at Salamanca. They all thought that Wellington was ‘only good at defensive battles’ but incapable to go on the attack.

India was too far away, the Royal Navy stood in the way of French communications and France under Napoleon was concerned with conquering Europe, so the important Battle of Assaye was unknown to them. This battle had taken place in 1803 and Wellington always thought it was one of his best:

“Assaye was 34-year-old Wellesley’s first major success and despite his anguish over the heavy losses, it was a battle he always held in the highest estimation. After his retirement from active military service, the Duke of Wellington considered Assaye the finest thing he ever did in the way of fighting even when compared to his later military career.” (link)

That reference to the huge losses is a clue: Wellington was always sparing with the lives of his men. He never sacrificed them when he could avoid it. Thus he only gave battle when he was sure he could win with the least losses – and win he did.

There’s one other point needed to fill in the background to the Battle of Salamanca: on the 11th May 1812 the PM, Spencer Perceval, was assassinated in the lobby of the HoC. The (lefty, of course) wiki entry reflects the general attitude of the whigs then, the Left now, towards the Peninsular War:

“Wellington’s force in Portugal was Britain’s only military presence on the continent of Europe. Perceval insisted that it remain there, against the advice of most of his ministers and at great cost to the British exchequer.” (link)

Yes – the Napoleon admirers always wanted an end to Wellington’s Peninsular war! There was one great moan by the ‘croakers’, the armchair generals in his own army. It was that Wellington had failed to attack Marmont earlier, in June. One explanation is that Wellington, who was aware of the situation in London after Perceval’s assasination, believed it better to see what new government would emerge. If that new government was prepared to recall him and end the British engagement in Portugal and Spain, then starting an attack which he might not have won would have been a disastrous move. The other explanation was the eternal difficulty with supply:

“Wellington made his plans on the assumption that he would be ready to advance in the second or third week of June. The six week delay from his arrival in northern Portugal was not primarily to give his troops a rest, valuable though that would prove. The time was needed to re-supply Ciudad Rodrigo and Almeida – he had been furious that neither fortress had had sufficient stockpiles to sustain them in the face of a long blockade when Marmont advanced in April – and to build up large forward magazines to support the army in its advance.” (link)

So – no attack in June, and the ballet of two armies marching parallel to each other started a month later, culminating in the Battle of Salamanca. Marmont and Wellington observed each other like hawks, the one getting it right, the other – not:

“On the morning of July 22, the frenzy of manoeuvre reached a climax and was brought to an end. Wellington had actually been ready to give Marmont best and beat a retreat to Portugal when, watching their outposts and his own skirmishing around the high ground beyond Salamanca, he was heard suddenly to exclaim […] to his Spanish liaison officer that the French were ‘lost’.” (From John Keegan, “The Mask of Command”)

This is how other contemporaries remember that moment:

“Eating lunch in a farmyard, Wellington watched the French through his telescope. Seeing their lines over-extended and vulnerable, he flung away the chicken leg he had been eating. “By God, that will do!” he exclaimed.” (link)

The next Wellington quote has also been handed down by eyewitnesses, again it’s typical for the way he conducted his battles. This is what happened: he rode off at full speed to the division hidden behind a hill on his right. This division was commanded by his brother-in-law, Edward Pakenham. John Keegan writes in ‘The Mask of Command’:

“Riding up, Wellington – who had outdistanced his staff – tapped him on the shoulder and said, ‘Ned, d’ye see those fellows on the hill? Throw your division into column; at them! and drive them off the hill.’ A bystander recalled that his orders came ‘like the incantations of a wizard’.”

Well, Pakenham did as ordered and the French were driven back and beaten, Marmont himself was wounded, other generals died. Rory Muir in his Wellington Biography ‘The Path to Victory 1769-1814’ writes:

“No one was more delighted by the victory than Wellington himself. He told Pole [his brother William Wellesley-Pole]: ‘I never saw an Army get such a beating in so short a time. I am afraid to state the extent of the Enemy’s loss; it is said to be between 17,000 & 20,000 Men … What havoc in little more than 4 hours!’”

It was a decisive victory which opened the way to Madrid. It was a victory gained by attacking, not by defending, in contrast to the victories over Masséna and Ney in Portugal at Busaco and at the Lines of Torres Vedras. Btw, Wellington managed to keep the construction of the Lines of Torres Vedras so secret that even his army of croakers had no idea they existed – an existence which took Masséna totally by surprise.

The assessment of the Battle of Salamanca by the French general Foy is interesting. Foy commanded the division on Marmont’s right wing and was the only one able to retreat in order. I bet Napoleon didn’t read it:

“The battle of Salamanca is the most masterly, the most considerable … and the most important in its results, battle that the English have gained in modern times. It raises Wellington almost to the height of the Duke of Marlborough. Previously one recognized his prudence, his choice of positions, his ability in using them; at Salamanca he showed himself a great and able manoeuvrer; he kept his dispositions hidden almost all day; he watched our movements in order to determine his own; he fought in oblique order; it was like one of Frederick the Great’s battles.” (from Rory Muir: “Wellington: The Path to Victory 1769-1814”)

That’s quite an accolade for a mere Sepoy general!

Looking at the battle of Salamanca, there are striking similarities with the Battle of Waterloo. At Salamanca Wellington’s tactics from the masterly use of the landscape to hide troops, the use of the reserve slope, the flank attacks, the timely use of the reserves, are all present. So is his constant movement from one place to the other – unlike Marmont who sat stationary on that hill where he got wounded and had to be carried off the field.

Wellington was always keen to see for himself what was going on rather than rely on reports. At Assaye, according to contemporaries, he was riding along the front when one of his aides told him that he was going towards enemy cannons which were already firing at him. ‘So they are’, said Wellesley (not ennobled at that time) and coolly rode off. Thus at Waterloo where he had to get into the squares when Ney’s cavalry attacked. Thus at Salamanca, with the recurring theme that his aides were unable to keep up with him:

“There was some fighting and at one point Wellington and his staff were caught up in a cavalry melee. According to John Cooke of the 43rd: ‘The Earl of Wellington was in the thick of it, and escaped with difficulty. His straight sword drawn, he also crossed the ford at full speed, smiling. I did not see his lordship when the charge first took place. When he passed us, he had none of this staff near him; he was quite alone, with a ravine in his rear.’ (from Rory Muir: “Wellington: The Path to Victory 1769-1814”)

Napoleon had other, Russian things on his mind though. Despising Wellington as mere Sepoy general, he hadn’t realised that Wellington had learned how to win in India, from tactics to the importance of logistics and supply.

When Wellington said after Waterloo: “They came on in the same old way and we defeated them in the same old way.” – that doesn’t just refer to the French addiction to columns as opposed to the British lines, it refers to their not using the landscape of the battlefield properly.

Now you know some reasons why I’m a card-carrying ‘1st D of W Fan Club’ girlie! Perhaps some Puffins will join that club – else I’ll not hesitate to serve up some more instances of Wellingtonia for your instruction!

© colliemum 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file