Just a few of the umpteen songs I could have chosen!

Apparently I’m a bit of a numpty for not making the link between “The Longest Day” and Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony! So, with June being the 76th anniversary of D-Day and hubby popping downstairs to invest a few hours to watch the film, I began to have a dig around.

In January 1941, Victor de Laveleye, former Belgian Minister of Justice suggested that Belgians use a “V” sign as a gesture of defiance given that both French and Flemish speakers in German-occupied Belgium would recognise the V as the first letter of “victoire” and “vrijheid.” The campaign spread across BBC European services broadcasting to Special Operations Executives in occupied areas and was given a “sound” being the letter V in Morse code played out on the timpani. But going off on a short tangent, where did that Morse code come from?

Samuel Morse was born to an American pastor towards the end of the 18th Century. Growing up as a strong Calvinist, Morse became an established artist of his time, co-founding the National Academy of Design in New York City in 1826 and serving twice as its president (1826-1845, 1861-1862).

Archives of American Art / Public domain

However a journey by ship returning from Europe in 1832 set Morse on his quest to develop the single-wire telegraph. Setting his paintings to one side, he began his work on the electromagnetic telegraph. Morse fought many legal battles over subsequent decades in order to be recognised as the sole inventor and to overshadow the work of “the most unprincipled set of pirates” as he called his opposition in a letter to his brother dated April 1848.

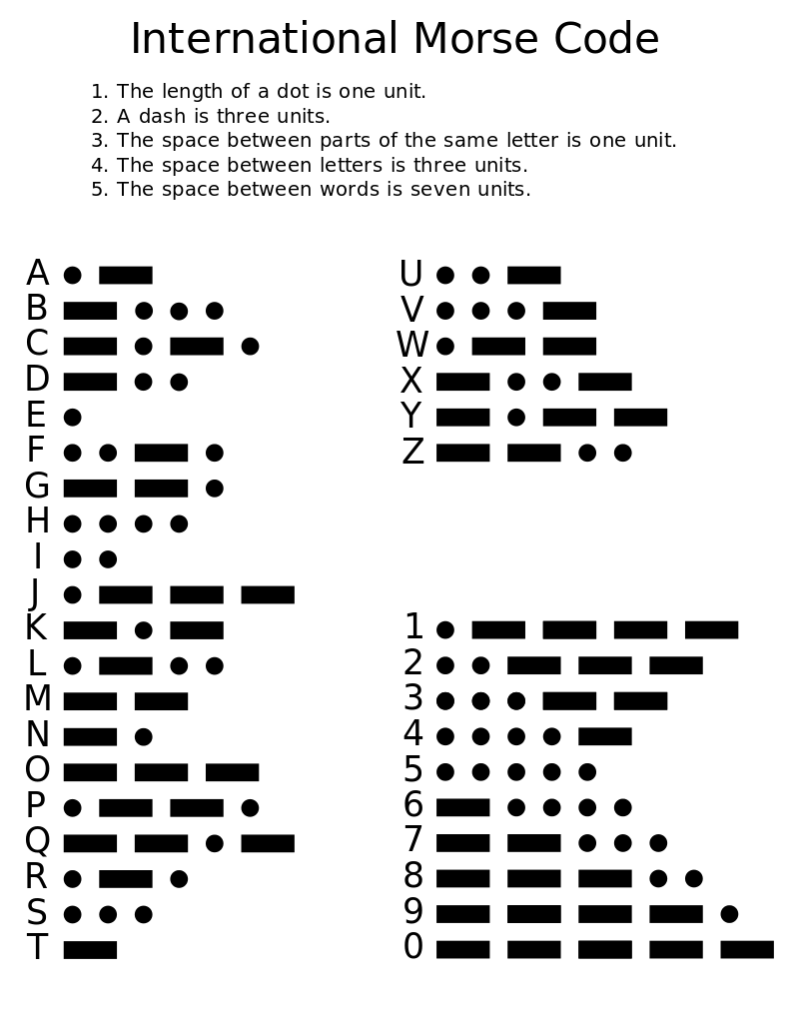

The Morse system for transmitting long-distance messages in code initially used a stylus to make indentations on a moving tape. The code was to be based on numerals which could be translated into words using a code book. However, Morse’s original thinking was developed by Alfred Vail in 1840 to include letters and special characters. The unique code for each letter was assigned by Vail depending on the frequency of use of that letter.

Rauantiques / CC BY-SA

With Morse’s original telegraph, the receiver’s mechanism made clicking sounds as it marked the paper. The operators were able to translate these sounds into the dots and dashes we know today in time reading the dots as “di” or “dit” and the dashes as “dah.”

Morse code could so easily have been known as “Vail Code” or “Gerke Code” recognising the refinements made along the way by Alfred Vail and Friedrich Clemens Gerke however the name has stuck.

Rhey T. Snodgrass & Victor F. Camp, 1922 / Public domain

Since the Second World War, Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony (written between 1804-1808) has sometimes been referred to as the “Victory Symphony” given that the rhythm of the opening bars mirrors the Morse “di-di-di-dah” of the letter V. However the piece was written 30 years before the development of the Morse / Veil / Gerke code so the symphony was not an intentional use of Morse code embedded within music. However there are plenty of examples (umpteen in fact)!

Starting off with a missed opportunity – S.O.S by Abba. I have looked through the score and listened as many times as I can bear but I can’t find a “di-di-dit / dah-dah-dah / di-di-dit” anywhere. Dohhhh! Did they really miss the obvious opportunity? The opening bars might vaguely spell out 44HU but I’m sure that’s not Swedish for any sort of cry of alarm!

So who did manage to get S.O.S. right? A couple examples in fact. Let’s start with London’s Burning by The Clash (1977, CBS Records). The lyrics tell the frustrations and anger of being a young person in London in the late 1970s. Some also suggest the lyrics are about nuclear meltdown and London calling for help. Guitarist Mick Jones spells out S.O.S. as the song fades.

Six years later, and Duran Duran released the Union of the Snake (1983, EMI). Simon LeBon has always been reticent to explain his lyrics however Nick Rhodes admitted to making the last minute addition of S.O.S. on the keyboard.

But how about something a bit more original? As Canadian rock band Rush were flying into Toronto Pearson International Airport they heard the call sign for the airport come over the pilots’ radio in Morse – dah-di-dah-dah / dah-di-dah-dah / dah-dah-di-dit – being YYZ. Geddy Lee and Neil Peart picked up the rhythm from that call sign and incorporated it into the introduction based on a 5/4 time signature.

More ambitious were German group Kraftwerk who stretched themselves to more than three letters in the title song from their Radio-Activity album (1975 Kling Klang). The song features the themes of radioactivity and activity on the radio. The inclusion of the hyphen is thought to be a reference to Kraftwerk’s sense of humour! At around 3:00 minutes into the composition, the letters R-A-D-I-O-A-C-T-I-V-I-T-Y are played out on the keyboard.

Some artists have taken the opportunity to use Morse code to hide messages within their works. Mike Oldfield, getting increasingly frustrated with his relationship with Virgin Records, sent Richard Branson a personal comment on Amarok (1990; Virgin). His missive to Branson starts at 48 minutes in. It’s not clear but apparently it starts “di / di / dah / dit, dah / dah / dah, di / di / dah / dit, di / di / dah / dit.” Not surprisingly this was one of his last albums with the label!

And to the final and perhaps most familiar theme tune containing the code – Inspector Morse (and the prequel Endeavour). Australian-born composer Barrington Pheloung used a Morse code motif to open the theme tune in which (using a very heavy dollop of artistic licence when it comes to consistency of speed of each di and dah) we get the M-O-R-S-E spelled out. Rumour has it that Pheloung would sometimes hide other clues in the sound track – sometimes spelling out the killer’s identity.

Tejvan Pettinger / CC BY

So as The Longest Day has now finished I’ll just flick back to the title and why I used the word “umpteen.” Apparently the word “umpty” is from Morse code slang for “dash” and was first attested from the turn of the 20th century. It means “of an indefinite number” or a number that’s not worth the effort of trying to work out exactly.

© Hamster Wheel 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player