To these gloomy pandemic-filled days, I’d like to bring a little cheer. For months I have, of course, not ‘read the comments’ posted by this assortment of scoundrel and rapscallion Fraterculae. Without having viewed such conversations, it’s occurred to me that a fair number of you good Puffins take pleasure in a drop of the old amber nectar (a.k.a. laughing water).

© Going Postal 2020

But have you ever gazed into the golden depths of your glass and wondered about the folks who supped the first sherbets?

As I’m sure you’ll know, and be thankful for, beers are widespread and local brews can be found in almost all parts of the world. Some say that beer takes third place among the world’s most consumed and appreciated drinks (with only water and tea knocking it into bronze position).

But were you aware that by raising a glass of a decent barley pop you are continuing to honour an ancient tradition? In fact, this tradition is especially long-standing. As it happens, beer is one of the oldest alcoholic drinks in the world. Yes, your brewski, that most precious of liquids, dates back a very long time, well pre-dating wine.

You might ask ‘how long?’

Well, quite astonishingly the roots of beer and brewing begin with the ‘Neolithic Revolution’ around 12,000 years ago. This was a period of tremendous change, as humans began to transition (note: proper use of ‘that’ word!) from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a more settled, agrarian way of life. The change was marked by the beginnings of the domestication of a variety of plants. This led on to crop cultivation and the birth of agriculture. This shift happened at separate times, quite independently, in different parts of the world.

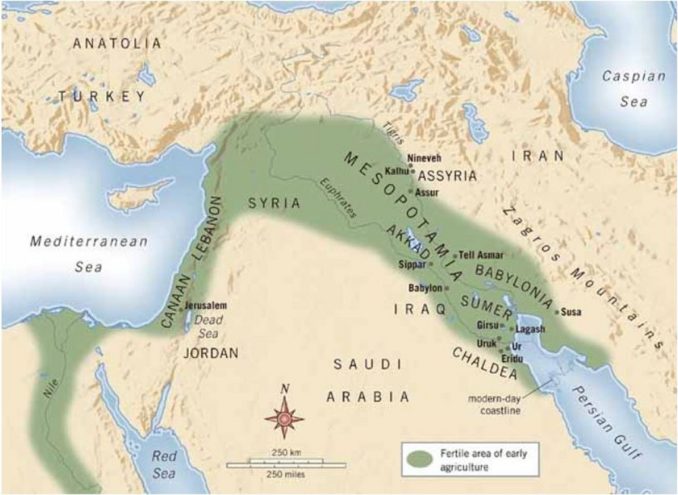

One of the regions in which life was transformed in this manner was the Fertile Crescent, a swathe of land covering modern-day Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, Jordan, north-eastern Egypt and the Nile valley, south-eastern Turkey and the western edges of Iran.

© Ted Mitchell (Public Domain)

Barley, one of the main ingredients of modern beers, was one of the first crops to be cultivated in the Fertile Crescent, along with emmer wheat, einkorn wheat, bitter vetch, peas, lentils, chickpeas, and flax. Rye was also cultivated. Oats were less common, this being more of a northern crop. With a wealth of grains available, because they naturally contain sugars and/or starches, just about any grains or cereals can undergo fermentation (including spontaneous fermentation). This means it is possible, perhaps even likely, that beer or beer-like consumables would have swiftly arrived on the scene.

We know that beer was important to ancient people. There are a good number of reasons why this would have been the case. Consuming a brewed beverage might have been a healthier option, as many local water sources were unlikely to be of a particularly good quality. The fermentation process is both an effective method of killing bacteria and waterborne disease and it increases the grains’ nutritional value, so beer would be valued as a food source as well as a beverage. The process of ‘malting’ also helps to preserve grains.

There is, of course, the added bonus of a noticeable psychotropic effect (affecting behaviour, perception, emotion), or ‘buzz’, from the alcohol content. This could explain, perhaps, why it may have been adopted for ritual uses, including to honour the dead. Indeed, to this day we still do the same when we raise a glass to salute lost friends.

To date, no-one is certain how the process of beer-making was discovered, although it has been suggested that serendipity played a part when grain, or possibly foodstuff such as bread, accidentally got wet. There are wild yeast spores all around us, in the air and on many surfaces. Any lucky yeasts to encounter this soggy banquet would have taken full advantage of a free lunch! Saccharomyces yeasts (and some from other genera) would settle in, feed and reproduce, digesting their carbohydrate meal and fermenting it to produce alcohol.

As to who first dared taste this new-fangled oddity, we’ll never know. But squandering any food, even a peculiar-smelling mushy gloop, would have been unthinkable in the past. Quite quickly, someone would have looked for ways to make it palatable. Waste not, want not!

Once established as a (relatively) harmless substance with a flavour people enjoyed, methods to deliberately produce beer in antiquity could be developed. By testing these methods empirically (using flavour, aroma, palatability and appearance) and refining them, the resulting brew could be improved. This ensured it was enjoyed across the social hierarchy and by all ages, from labourers to the nobility, and from childhood through adulthood.

Simple as this may sound, these developments should not be underestimated. Manipulating living organisms (those yeasts) to produce and improve a valuable beverage means that beer-making could be viewed as humanity’s first foray into biotechnology.

But how do we know about this early beer and brewing?

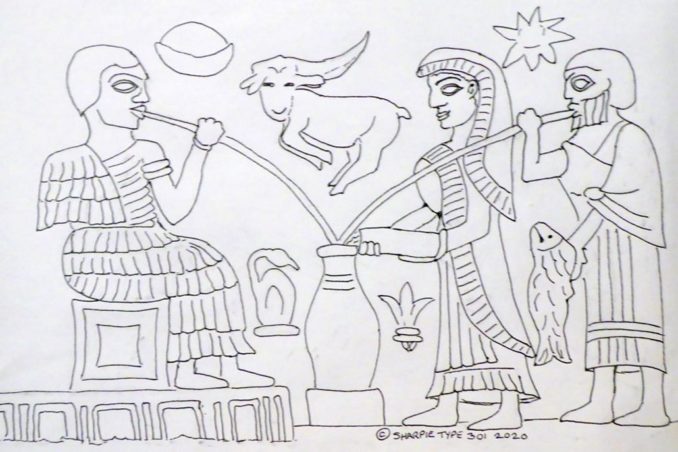

Until not long ago, the first material evidence of beer from the Fertile Crescent region was believed to be a Sumerian tablet, dating to around 4,000 BC, a sketch of which can be seen below. This depicts people using reed straws to sip beer from a communal bowl.

© SharpieType301, Going Postal 2020

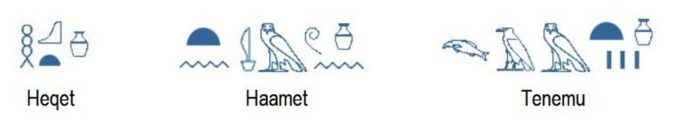

In addition, some of the world’s earliest known ‘writing’ (in the form Sumerian archaic cuneiform script and, later, Egyptian hieroglyphs) refers to the production and distribution of beer. This is a bigger deal than it may at first appear, as the earliest records were typically economic and administrative documents, so not commonplace and often only accessible to the elite. That beer is mentioned demonstrates the importance of this precious commodity to the ancient world. As an interesting aside, early writings also indicate that most brewers were in all probability female.

The Egyptian goddess of childbirth and beer was Tenenet. Associated with beer and brewing, she is often depicted wearing a cow uterus on her head. It is believed that her name stems from the word ‘tenemu’, one of the words for beer. Reference to beer in ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic records is relatively common. One nice example is an inscription from around 2200 BC, which reads: “The mouth of a perfectly contented man is filled with beer”.

During Egypt’s Old Kingdom period between c. 2686–2181 BC, (the ‘Age of the Pyramids’), grave goods in Egyptian tombs included wooden models representing important things from life. Small wooden boats, tableaux depicting the production of food and drink, craftsmen and workshops, and statuettes portraying professions such as scribes or soldiers have been found.

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain Dedication. Licensed under CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0).

Indeed, even the Egyptian pyramids might not have been built without beer. The Pyramids of Giza were constructed between around 2580 and 2560 BC, and wages were often paid in beer (and other supplies). Each worker was ‘paid’ a daily allotment of four to five litres of beer. Not particularly intoxicating, some beers were thick and sweet so provided both nutrition and refreshment. The Egyptians also modified Sumerian brewing techniques to produce a smoother, lighter beer. This was consumed at festivals and had the great advantage that, to drink it, straws were not needed as it could be poured into a cup or glass to drink.

Egyptian brewers made several different types of beer, classified according to alcoholic strength, colour and flavour and had “beers of different colours and strengths for different occasions: beers for high days, feast days, medicinal beers – one for toothache, made with rhubarb, and one injected as an enema if you had piles”, each with its own name.

© SharpieType301 2020

The Epic of Gilgamesh, dating to c. 2100 BC, is a Mesopotamian epic poem considered to be the earliest surviving great work of literature. Recorded on a series of stone tablets, in one of them the priestess Shamkatum tames the ‘wild man’ Enkidu by giving him beer to drink. The poem records that “… he ate until he was full, drank seven pitchers of beer, his heart grew light, his face glowed and he sang out with joy.”

The earliest recipe for brewing beer recorded in a written form comes from around 1800 BC. It is part of a Sumerian poem which honours the guardian, patron, and protector of brewers and beer, the goddess Ninkasi. Recorded on clay tablets, and called the Hymn to Ninkasi, the ‘brewing song’ praises Ninkasi for soaking malt in a jar and spreading mash on reed mats, among other things. Although the written record dates to 1800 BC, the poem is unquestionably older, in all probability harking back to an oral tradition.

With the kind permission of Kolenda Art Glass. © www.kolendaartglass.com 2013

Beer also features in the Babylonian legal framework, the Code of Hammurabi, which dates to about 1754 BC. This is mankind’s oldest existing set of laws, and not only does it set fair prices for beer, but it includes laws regulating beer and beer parlours. Harsh penalties are laid out for non-compliant brewers and bars. A brewer who diluted his beer could be drowned in his own vat, and a tavern owner who overcharged patrons could be put to death!

To this point, all evidence for beer and brewing comes from material evidence (artefacts made by people) or from documentary evidence (records, inscriptions, legal texts).

The first scientific evidence of a barley-based beer was discovered at Godin Tepe in the central Zagros Mountains of what is now Iran. Godin Tepe dates to at least the 5th millennium BC (5000-4001 BC) and the evidence came from analysis of a yellowish deposit inside a large, wide-mouthed jug. This was identified as calcium oxalate, a major component of ‘beerstone’ which settles out on surfaces of vessels in which barley beer is fermented and stored. These analytical results support the material evidence provided by the tablet shown in Figure 2. Until recently, the Godin Tepe brew was believed to be the oldest evidence of beer and brewing.

What was ancient beer like?

Ancient beer was quite unlike modern brews. You may have heard beer being described as ‘liquid bread’—well that would be a pretty accurate definition of some ancient brews. Hops were unknown in the Fertile Crescent region, so the beverage would not have kept well and was made for almost immediate consumption. Multiple ingredients produced a cloudy, low-alcohol beverage, often sweetened (brews were often fortified with dates and honey and flavoured with herbs and spices). The consistency was more like a thin porridge or gruel, with a lot of sediment which needed to be strained before drinking.

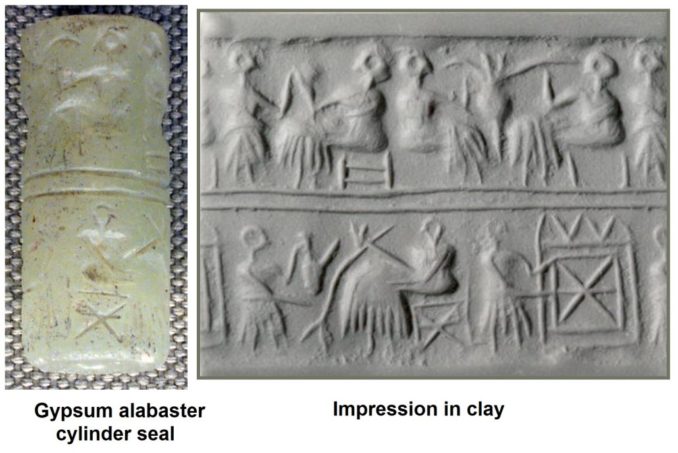

This was why Mesopotamian drinkers used reed straws, which had filters at the bottom to allow them to sup the liquid and avoid the slightly bitter, semi-solid sediment. This practice can be seen in banqueting scenes from cylinder seals. Possibly the clearest image to date is from a Lapis lazuli seal in the British Museum’s collections, however a similar image from a Gypsum alabaster cylinder seal below is shown.

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain Dedication. Licensed under CC0 1.0 Universal (CC0 1.0)

Interestingly, there has long been a slightly ‘controversial’ theory that it was ancient peoples’ appetite for beer (rather than a fondness for bread) that first started them on the road to domesticating cereal grains, permanent settlement and the development of the earliest civilizations.

Could this be true?

It appears so. Recent research, from analysis of material from Raqefet Cave in Israel, seems to support this theory. In fact, the evidence from Raqefet Cave has pushed back the date for ancient beer and beer-making in the Fertile Crescent quite considerably.

Raqefet Cave is a Natufian site near what is now Haifa. The Natufians were a semi-nomadic, foraging people, pre-dating settled, crop-producing agricultural societies. The fact that beer was important to them gives a strong indication that the origins of beer are not irrefutably related to ‘agricultural’ surplus. Because the cave is unlikely to have been inhabited year-round, and part of it was used as a burial site, it is thought that the beer made there could have been for use for ritual purposes, perhaps meeting spiritual needs as part of funerary feasts to venerate the dead,

To date, at a staggering 13,000 years old, this is the oldest evidence of man-made alcohol in the world. Contrast this with the oldest evidence of beer and brewing discovered in Britain, from Cambridgeshire, which dates to the Iron Age, around 400 BC – yep, that Fertile Crescent beer is pretty old!

Wait!… that Natufian stuff is really old – how do we know this?

Well, there are no written records, no pictograms to interpret so, until quite recent times, archaeologists inferred whether an object or vessel might have served a special purpose from factors like shape and the context in which it was found. Indeed, approximately 99.9 % of the human past falls before historical records of any form. Luckily, that’s where one of my interests, you might say my area of expertise (as my husband calls it ‘my career in ruins’), comes in rather handy.

I am not a traditional archaeologist. You know the ones—those scruffy, long-haired, beer-guzzling types in holey sweaters, bum up, head down, digging holes in the ground or raiding tombs as a pastime. Nope, I trained as one of the back-room boys and gals—the ones in white coats in a laboratory trying to figure out what the heck is in that ancient lump of muck those pesky diggers have brought us this time. When material is sent to us straight from excavations to investigate, it’s usually called post-excavation analysis.

More commonly though, the application of scientific techniques to ancient material is referred to as archaeological science. This broader term is more appropriate because analysis is also carried out on objects which may have been in museum collections for decades (sometimes half-forgotten in dusty old boxes!). This has potential to revise our understanding of the past, sometimes quite contentiously, something of which I have first-hand experience.

Archaeological scientists are a bit like jack-of-all-trades—our remit is to apply scientific techniques to the study of the past. Archaeological science is an interdisciplinary area, incorporating biology, chemistry, physics, materials science, anthropology and it can sometimes even draw knowledge from other subjects, geology, sociology, psychology or economics. This allows us to find out more about ancient objects. Not just their identity and purpose, but what they are made of, how they were made, how they were used or altered, where they came from, were they local or traded from afar, when they date to… and much more besides.

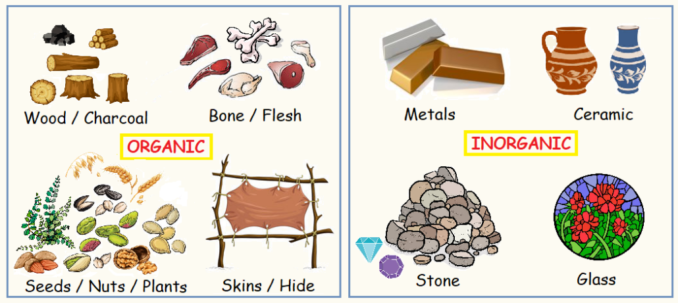

Although microscopy is often a suitable first step for examining many types of material, chemical and physical scientific techniques, often high-tech, can be used to examine organic and inorganic material, and also composite materials such as bone, which is classified as organic, but contains a high percentage of inorganic mineral (hydroxyapatite).

© SharpieType301 2020

But, let’s get back to the beer!

At Raqefet Cave, traces of plant residues were found inside stone mortars cut into the bedrock in the floor of the cave. Physical evidence (wear patterns in the stone) and analysis of these residues showed some mortars were used to store cereals, including wheat/barley malts. However, one of the mortars stood out. This was used for food-processing—to pound, cook and brew beer. From the interior, the analysts discovered starch residues and phytoliths (microscopic silica or mineral particles taken up from soil and deposited in some plant tissues) which were typical of the transformation of barley and wheat to beer.

To quote Li Liu, the Stanford University archaeologist who led the Raqefet Cave research team: “Alcohol making and food storage were among the major technological innovations that eventually led to the development of civilizations in the world, and archaeological science is a powerful means to help reveal their origins and decode their contents“.

Beer and beer-making usually falls into the organic category because beer is produced from grain (usually barley, but also other grains) by yeast fermentation. However, as we’ve seen earlier beerstone is for the most part inorganic. Scientifically, it’s a composite, a mixture of calcium oxalate (the hard substance found in kidney stones) and proteins from the grain, so evidence for brewing has a foot in both the organic and inorganic camps. The other major component of beer is, of course, water, which accounts for about 90 to 95 percent of today’s brews. This organic-inorganic combination is rather helpful as it means that a range of different techniques can help us identify evidence of beer production and use.

One of the world experts in this field is the ‘Indiana Jones of Ancient Ales, Wines, and Extreme Beverages’. This bearded superhero is, in truth, Dr. Patrick E. McGovern, Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum. A man with a background worthy of an article in his own right, he is one of the pioneers of the relatively recent field of molecular archaeology, one component of archaeological science.

Molecular archaeology can be split into two main strands, one relating to analysis of organic archaeological materials, the other to analysis of inorganic materials. The techniques that can be employed range from the simple, not needing any sophisticated instruments (e.g. Feigl Spot Test to detect calcium oxalate, which could indicate beerstone) to more complex analysis of ancient residues, whether these are visible on the surface, or absorbed inside pores in the walls of pottery vessels.

Pat McGovern and researchers with similar interests (including yours truly) have developed expertise in organic residue analysis, a branch of organic or biomolecular archaeology. To identify particular products of archaeological interest, what we look for are ‘biomarkers’. These are molecules, archetypally biological, or a collection of molecules which make up the ‘chemical fingerprint’ of materials exploited by humans in the past. Extracting and chemically identifying unique biomarkers is essential for successful and accurate residue analysis.

However, a significant challenge is that many compounds of archaeological interest are not unique to only one natural product. So how can we be sure what we’ve found is what we think it is not something completely different? For example, the Feigl spot test for oxalate may show evidence of beerstone, but oxalates also occur naturally in relatively large amounts in spinach and rhubarb. To hone-in on the origin of what you are analysing, you would look to identify a range (or suite) of biomarkers, including ones that don’t occur in the vegetables above, so you could rule them out.

Of the high-tech analytical techniques available, particularly useful ones have included diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS), high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), gas chromatography (GC) and gas chromatography mass spectrometry (GC/MS). For those of you interested, Wiki has a lot of fascinating articles on analytical techniques.

But before I wrap up, there are a few more beery facts that you might not be aware of. These relate to several attempts to recreate and revive ancient beers.

Patrick McGovern, who identified the beer from Godin Tepe, went on to collaborate with the Delaware-based Dogfish Head Brewery to create several modern interpretations of ancient beers, recipes for which have been reconstructed using residue analysis.

- Midas Touch – http://bitly.ws/8j6U

- Chateau Jiahu – http://bitly.ws/8iZo

- Theobroma – http://bitly.ws/8iZ5

- Birra Etrusca Bronze – http://bitly.ws/8iZu

- Ta Henket – http://bitly.ws/8iZs

- Sah’Tea – http://bitly.ws/8j7B

All images licensed under CC BY 2.0

The first of these was their ‘Midas Touch’. This recipe, first marketed in June 2001, was brewed with honey, white Muscat grapes, and saffron, and is based on molecular evidence found in a 750 BC tomb believed to have belonged to King Midas in Gordion, the capital city of ancient Phrygia.

They worked together again in 2006 to create a second beer, ‘Chateau Jiahu’. Although confirmed by residue analysis, its ingredient list was discovered in a 7,000 BC tomb in China and included hawthorn fruit, sake rice, barley, and honey.

A further collaboration in 2008 gave rise to ‘Theobroma’, based on chemical analysis of pottery fragments found in Honduras. This replicates the earliest known alcoholic chocolate drink, which was thought to have been used on special occasions. It includes honey, ancho chilies, ground annatto seeds, cocoa nibs, and cocoa powder.

Their ‘Birra Etrusca Bronze’, recreating an 800 BC recipe, was based on analyses of drinking vessels found in Etruscan tombs. Fermented in bronze vessels, it contains hazelnut flour, pomegranates, Italian chestnut and other honeys. Although hops were added, the bitter flavour largely comes from gentian root and Ethiopian myrrh. It’s then fermented in bronze vessels, traditionally used in Italian brewing.

Dogfish Head take ancient ales seriously and have developed several others. Their ‘Ta Henket’ is unique. Not a re-interpretation, it carefully re-created an ancient Egyptian recipe recorded in hieroglyphics. The yeast for this beer has been carefully cultivated using traps to track and isolate wild yeast strains from the night air in Cairo, Egypt. Quite an endeavour. Their ‘Sah’tea’ is a modern take on a 9th-century Finnish beer. For this brew, the wort is caramelised over white-hot river rocks. The beer is fermented with German weizen yeast (a wheat beer yeast) and flavoured with juniper berries and black tea. Perhaps one of their strangest yet is ‘Kavsir’ (which Pat McGovern calls Nordic grog). This is a curious hybrid of beer, fruit wine, and mead and is flavoured with yarrow, lingonberries, cranberries, bog myrtle, and birch syrup. Some fascinating videos can be seen at: http://bitly.ws/8b7Q

Somewhat further back, in 1988, the owner of San Francisco’s Anchor Brewing, Fritz Maytag, began working on the Sumerian Beer Project with Prof. Solomon Katz (from University of Pennsylvania’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, where Pat McGovern is now Scientific Director). The aim was to produce a beer made to the Hymn to Ninkasi recipe. They succeeded, and the original batch of ‘Ninkasi’ beer was presented at the 1989 conference of the American Association of Micro-Brewers, in large pottery jars the way the Sumerians would have served it. Anchor Brewing went on to create a second batch in 1992. This version, which was offered in a public tasting, used a greater quantity of ‘bappir’ (a hard, twice-baked, honey and barley flour Sumerian bread). This was created from a recipe which included an ancient strain of wheat called emmer. Sadly, however, Anchor has no plans to market their ‘Ninkasi’ beer commercially.

Another brewery interested in ancient beers is the Ohio-based Great Lakes Brewing Company. Although they did not plan to sell it to the public, they also recreated Sumerian beer using the recipe from the Hymn to Ninkasi. The ingredients of the first beer they produced included coriander, cardamom, figs, dates, and pomegranates. They also followed the Sumerian process, using only a wooden spoon and clay vessels (which were modelled on artifacts excavated in modern-day Iraq). They malted the barley on the roof of the brew house and used a rich, yeasty, brick-like ‘beer bread’ (bappir) to produce a warm, slightly sour beer full of bacteria. Although this brew didn’t make it to the public, they subsequently created two beers inspired by Sumerian brewing. ‘Enkibru’ was the more traditional of the two, as it was brewed, fermented and served in clay vessels using the techniques described in the Hymn to Ninkasi. Their other beer, ‘Gilgamash’ was brewed without hops but using modern equipment. This includes traditional Sumerian ingredients of dates, coriander, cardamom, figs, dates, and pomegranates.

Taking a slightly different approach, yeast found in a bottle of 220-year-old beer has also been used to recreate an ‘old’ beer. An unopened bottle was recovered from the wreck of the Sydney Cove, a small merchant ship that ran aground and sank near Tasmania in February 1797, while heading from Calcutta to Port Jackson. Both Brettanomyces and Saccharomyces brewer’s yeasts were identified. Brettanomyces is no longer used in commercial brewing but was common in old-style brewing. A team of researchers from Australia, France, Germany, and Belgium used the yeast and followed a traditional recipe from the era to brew ‘Preservation Ale’ a mild, fresh-tasting, slightly sweet beer.

A similar story comes from Israel, where researchers extracted living yeast which survived for thousands of years in pores in the surface of ancient pottery used to make and store beer. They believe that the beers they have brewed are akin to beverages which would have been enjoyed by Biblical characters such as David and Goliath. The pots and sherds were excavated from four sites in the Holy Land. The oldest dates to the Canaanites, around 3,000 BC, while other sites were once inhabited by Philistines, Egyptians and early Hebrews. The team and some certified beer tasters all tasted the brews from all six strains of yeast. They declared them to be ‘drinkable’.

Finally, and a little closer to home, in 1996 the Scottish and Newcastle Breweries brewed an authentic recreation of ancient Egyptian beer, ‘Tutankhamun Ale’. Scottish brewer, Jim Merrington, spent six years painstakingly reconstructing this vintage beverage, in collaboration with Dr. Barry Kemp (archaeologist and Egyptologist) and Dr. Delwen Samuel (archaeobotanist) from Cambridge University.

The beer they recreated was first made in Amarna, a short-lived city built in 1346 BC by the Pharoah Akhenaten for himself and his queen, Nefertiti, in honour of the sun god Aten. The remains of Amarna lie on the east bank of the Nile, some 200 miles south of Cairo.

Marknesbitt / Public domain

The finished beer had a sweet and fruity aroma, with a touch of caramel and raw grain. It tasted rich, very malty, with a flavour reminiscent of chardonnay, sweet, heavy, and mouth-coating but with some astringency. At 6% alcohol it had a kick like a camel, but as Jim Merrington remarked, “It’s not a connoisseur brew, it’s for quaffing”.

There were only 1,000 bottles of ‘Tutankhamun Ale’ produced, which were sold at Harrods in London. The first bottle cost £5,000 and the other 999 in the numbered, limited-edition brew sold for £50 apiece, and that was back in the mid-nineties! Perhaps something to consider, LP?

I’ll finish with a final thought from George Herman ‘Babe’ Ruth Jr., one of the all-time greatest baseball players, a man famous off the field for his drinking, smoking and womanising.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, LC-F8-17004 [P&P]

© SharpieType301 2020

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file

Audio Player