June 25th, 1809.

We are returned to London. Our journey from Portsmouth was necessarily a slow one, as no stagecoach driver will countenance adding eight bears to his passengers. In any case, Fred deemed it prudent to conserve our little fortune from the sale of contraband, for our future in uncertain. So we walked the long road, alternately dusty and muddy, spending the nights in barns and subsisting on what Fred and Jem could shoot and we could catch. Once our day’s bag included a sheep brought in by Bruin. No questions were asked.

We were not troubled by footpads. One evening there a sound of scuffling in the bushes beside the road, and we saw several men running away. Eight bears sometimes do have that effect on people.

We halted near towns on our route – Petersfield, Hindhead. Guildford, Cobham, Chessington, Mitcham – and found inn yards where we could perform. Fred, the consummate showman, has worked up an act in which we recreate our adventures in the Peninsula through a series of dances, which we perform to the music of his flute while Jem tells the tale of our battles. By the time we reached the outskirts of London this had grown into a species of ballet which took over an hour to enact in its entirety and, to judge by our reception, was much liked by the audience. We arrived with an additional £64 16s 8½d in our purse. We do not know who gave us that halfpenny, but bless this economically charitable soul anyway.

On our return we visited our old quarters in the malodorous market gardens of Kensington, and discovered that no new tenants had been found, so we rented them again, for less this time after Jem had pointed out to the landlord that his premises had remained empty because ‘Nobody’d want to live in a place what stinks of shit.’ To be fair, you hardly notice after a day or two.

Fred visited London to enquire at the Admiralty about the progress of our prize claim. Not surprisingly, nothing had happened. He deposited our little fortune with Cox’s military agency at Craig’s Court in Whitehall, which often sees money from doubtful sources and does not enquire too closely into its provenance. As Vespasian remarked about the receipts from the public lavatories he established in Rome, pecunia non olet, money does not stink. Besides, it is a convenient place to receive any rewards that their naval Lordships might be kind enough to grant us.

Fred also took the opportunity to deliver Wellesley’s letter exonerating Jem from blame to the chief magistrate of the Runners. We trust that this should be the end of the affair.

Our old stable was not without a tenant. A ragged boy was asleep in a corner beside a cage containing a few bedraggled chaffinches. When he woke to find himself surrounded by bears he was seized with panic, but after he had calmed down he told us in broken English that his name was Giulio, and that he was an Italian orphan who sustained a miserable living by exhibiting his birds in the streets.

Many of us bears have seen the misery of captivity – the chains, the painful nose rings, the heavy sticks. We could not leave those birds imprisoned. We told Giulio that we would look after him as well as we could, but the birds must go free. To this he agreed, and we opened the cage and our hearts were lightened as they flew out.

June 27th, 1809.

The chaffinches did not go far. Accustomed to captivity, they are hopping around our quarters, and a pair has started building a nest in a bush outside the stable door. We constantly hear their simple song, a succession of quick notes accelerating into a trill and turn. Jem can imitate this admirably on his flute but, having perfected it, no longer plays it, as it sends the male birds into a frenzy of emulation.

We have included Giulio and three of his ragged friends in our ballet, playing the part of Portuguese irregulars. They are quick to learn and delighted to have a purpose for the first time in their brief lives.

July 5th, 1809.

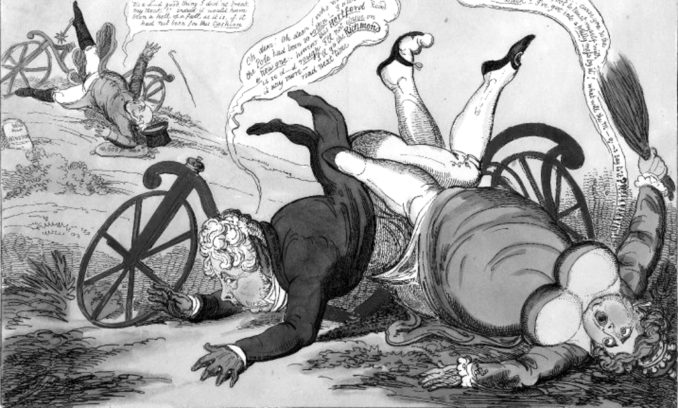

We were practising our dances in Hyde Park on Buck Hill, a slight eminence whose northern end overlooks the royal gardens. Whom should we see but His Highness the Prince of Wales, taking his morning exercise on one of the newly fashionable Velocipedes with his paramour the Marchioness of Hertford, and accompanied by the Duke of York?

No sooner had we noticed him than there occurred one of those accidents that sadly often attend the riding of these machines.

But, nothing daunted, the royal party picked themselves up and, having heard the merry music of Jem’s flute, recognised us and waved cordially. A hastily dispatched equerry conducted us into the royal precinct through a gate in the bastion, and we took His Highness’s mind off his bruises with a spirited rendition of our new performance. He was delighted, and said that we should have a chance to entertain his friends with it.

July 7th, 1809.

While it may be unwise to trust the word of princes, when it is in their interest to respond they do so with alacrity. This morning a messenger delivered a Royal Command in a beautiful cream-colourd envelope bearing a wax seal impressed with the royal coat of arms. We are to attend a ball at Carlton House in six days’ time, and perform for the guests. On the previous afternoon we are expected to rehearse our performance with the royal musicians.

All are tingling with anticipation, and our dances are well enough rehearsed, but there is the matter of clothing. Fred and Jem will need to be attired, if not in the dizzy height of fashion, at least well enough to gain admittance to a palace. The four boys will do well enough in their own ragged clothes, for the poor look much the same anywhere.

But what of us bears? After some discussion, we agreed that the males should wear waistcoats of various colours, and the females should have ruffled skirts similar to those we used for our dances in Portugal, though the original garments vanished long ago under the exigences of war.

July 8th, 1809.

One of Giulio’s sisters is a seamstress, and has agreed to make us the necessary garments for a reasonable fee. Fred has been to Whitehall to secure the necessary monies from the bank, and we have visited several pawnbrokers’ shops to find suitable garments for the men and curtains that can be transformed into costumes for the bears.

July 11th, 1809.

Our finery is ready, and we make a brave show. Perhaps the men’s evening dress is a little threadbare and patched at a close inspection, but no one expects us to pass ourselves off as aristocrats, and the effect is good enough from a moderate distance. The bears’ clothes, a riot of colour and flounces, are magnificent. Never was there such a fine ursine party.

July 12th, 1809.

We attended Carlton House for the rehearsal. It is a new and extensive building to the west of the King’s Mews at Charing Cross, and is appointed in a style of showy magnificence. A wooden stage has been set up at one end of the enormous ballroom, and it is here that we are to perform.

His Royal Highness paid a brief visit to the proceedings. He was looking a trifle jaded, perhaps having indulged himself the previous night a trifle more than is fitting for a person who, at 45, is no longer as resilient as he was in his youth. In the words of the proverb, Voluptati moeror sequitur, Sorrow follows pleasure.

I cannot speak very highly of the orchestra. Professional musicians are at best unreliable, and often arrive without having glanced at the music they are to play; then they complain that their part is too difficult. Sometimes they send substitutes to the rehearsals and arrive at the actual performance completely unrehearsed – and sometimes they do the opposite, which is worse.

It made me long to go back a hundred years to the court of King Louis the Fourteenth of France, whose renowned string orchestra, Les vingt-quatre Violons du Roi, played like no musicians before or since – probably under pain of death, but who would miss a few fiddlers?

Anyway, the players scraped their way well enough through the few popular tunes we use in our performance. The English audience are used to such things, and it will do. As Euripides wisely remarked, Δεὶ τοῖσι πολλοῖς τὸν τύραννον ἁνδάνειν, It is necessary for a prince to please the many. But Jem’s lively flute is more agreeable to my ears.

July 14th, 1809.

Last night’s performance was a triumph, and we are all glowing with pride. Our ballet was the principal act of the evening, as it deserved, and the account of our exploits in the war was received rapturously by the audience, who applauded us for minutes on end as we repeatedly took our bows.

Afterwards, the floor was given to general dancing and we mingled with the guests, whom we surprised with our agility in the latest dances. There was a great deal of food and drink to be had, and we availed ourselves of this as only bears can.

During the performance we had observed that a distinguished-looking man in the audience seemed to be stifling laughter. Fred chanced to meet him as they were waiting to be served at a side table. He was the Italian ambassador, and he told us that the war cries uttered by the four boys playing the role of Portuguese irregulars were in fact foul slanders against the Prince Regent uttered in the thickest Calabrian dialect, which even he had struggled to understand. The substance of their remarks, as he reported them, makes me blush. Let it suffice to say that certain transactions between His Royal Highness and the Marchioness of Hertford were the principal subject. How fortunate that His Excellency was the only person present who could understand them, and that, being a diplomat, he preserved a discreet silence about what he had heard.

Little Henry had rather too much to eat and drink, and was sick into a silver épergne filled with roses. Luckily this passed unnoticed in the general mêlée.As we left, I observed that the boys were clanking slightly as they walked. Fred and Jem halted and searched them, and relieved the four of them of what I estimate as eight pounds of silverware, to their disappointment. As you would expect, Jem is now slightly sensitive about such petty larceny, and handed the haul back to the major domo. ‘Lord bless you,’ was the response. ‘But there’s no need. You’d never guess how much the nobs snaffle at these affairs. Why, I reckon as how we lose near five hundredweight of silver a year.’

It seems that the Prince Regent simply orders more from Messrs Mappin & Webb, and that they are the real losers because he has not paid their bills for the past twenty years and more. The price of a Royal Warrant is a high one.

Jem now regrets his honesty, though not as much as the boys do. Still, we have profited by 50 guineas from the evening’s entertainment, and (unlike the unfortunate royal cutlers) we were paid on the spot, in gold. The money will be fairly distributed among us, and the lads’ share is probably more than they could have raised from their petty larceny.

We have mingled with the highest in the land, and have achieved what is probably a mere moment of fame. As Fred said to me as we settled down on the straw in our none too fragrant quarters, ‘Daisy, me dear ole bear, we done all right tonight. But what’re we agoin’ a do for an encore?’

Copyright © Tachybaptus 2019

The Goodnight Vienna Audio file