The call connected and was picked up. “Hello, oh it’s you. I was expecting you a while ago. Yes, I was there. They’re pretty bereft really. Whoever was responsible is unknown to them all, no leads other than to go through his associates step by step. They think it’s probably foreign, possibly Israelis, less possibly something domestic. They’ve no idea how he was identified. A leak inside probably, but no one’s found any trace and they’re looking hard. That was unwise of the Chief Constable. Luckily, she’s on the side of the angels, even if she doesn’t know it. We can’t afford this to leak out, got to keep a lid on things. Steady as she goes has brought us a long way. We can get it cleaned up later if required, but only when it’s died a death, but probably don’t need to, these things have a habit of fading away, just being forgotten. But we have to find out who was responsible, they could be a problem. Okay.”

The line went dead. Better tell some of the others.

She had come downstairs wearing Martha’s dressing gown when Josey woke in the afternoon. He was full of it, Martha had a young puppy, some sort of collie, and that was sufficient distraction for now. Sally could see Martha had a way with young children. They sat by the sitting room wood-burner drinking tea while Josey ran inside and out with the puppy who was clearly delighted to have a new young play-mate.

It was astounding, a hidden enclave in rural England, big enough to have its own steam railway line, a small harbour, a population running into the many thousands with a language descended from sub-Roman Brythonic, loosely related to Welsh and Cornish. Hidden for over 1,500 years, protected by a barrier that allowed no one to leave other than a chosen few, keeping out almost everybody without their being aware of it, just a few finding the gateways which closed and opened to those from the outside quite unpredictably. Governed by a High Steward on behalf of a reclusive Duke, with a Council of largely hereditary Seigneurs and elected parish based Stewards. No internal combustion, electricity or electronics of any kind, so still running on horse and steam power, illicitly importing certain benefits of the twenty first century such as medicines and insulation, but otherwise self-sufficient in its network of one principal and several subsidiary valleys, surrounding moorland, forest and hills, about the size of one of the smaller English counties. She had to pinch herself. There was so much to see and learn, her intellectual curiosity, which had lasted beyond her university days studying Classics and Italian, but had been ground down by the realities of working for the Foreign Office and then motherhood, was sparked into renewed vigour. How? Why? What were the drawbacks; it can’t be a utopia, which after all means ‘no place’?

Josey fell over the dog and started crying. “That’s enough questions for now,” smiled Martha, “I need to prepare some dinner as Iltud will be back by six I should think. Perhaps he will be able to help you find some more answers, but don’t worry, there’s no rush and you need to recuperate.”

Sally went to the front window after stilling her son and looked out. It was on the lower slope of a long valley looking south-west. In the far distance she could just make out the sea beyond a bay holding what seemed to be one large and several small mist-shrouded islands, the cold clear air aiding visibility. The sun was heading west glinting on the waves, such was the clarity of view on this fine day. The village, really a hamlet, was all around them, pretty stone and cob built white washed cottages, chimneyed, tiled roofs, gardens front and back which were clearly used for fruit and vegetables, often fringed by adjoining farm buildings, with the dirt and stone road between them descending the valley in a thick fringe of wild flowers.

It was idyllic, and then the memories of the previous day came rushing back, the fear so over-powering, her abandonment of her husband without having the courage to explain to him. Her shame, her deep shame. She heard the church clock strike six, out of sight to the right. She would go there first thing tomorrow and offer her penitence and thanks, but she needed more answers, perhaps Iltud would be receptive.

She heard the kitchen door close behind her and a man’s voice speaking quietly in the unfamiliar language, punctuated repeatedly by Martha‘s softer tones. “When’s dinner Mummy? When will we see Grandma and Grandpa?” Josey’s time clock had clearly gone off despite the puppy’s distractions.

“Not long now sweetie. Why don’t you go and wash your hands, you can’t eat with doggy hands.”

I’ve just told him another lie, another promise to myself broken, another selfish failing.

Evidently satisfied by this little bit of their own domestic routine, he toddled off to the water closet. At least they had some, albeit primitive, plumbing, and hot water for baths. Cleanliness seemed to be highly valued; thank heavens it wasn’t medieval in that respect at least.

The kitchen door opened, it was Martha’s husband. He smiled, somewhat stiffly she thought: he clearly wasn’t a natural extrovert and seemed to find the presence of complete strangers in his home something of a challenge, but he seemed to be trying to put her at ease.

“Martha says dinner won’t be long. You do eat fish? It’s Lent and we are quite traditional about it. Fortunately, the waters off the coast are rich here and it compensates for the ‘hungry time’ as we used to call it. A diet of salted meat and cheese would be so boring otherwise, and we try to minimise what we bring in from Logres.”

“Where’s Logres? And what do you mean by the ‘hungry time’?”

“Sorry, England, the rest of the mainland really. The ‘hungry time’ is the old expression for the time at the end of the winter and before the new season’s crops and animals are ready for harvesting, when we have to live off preserved foods from the previous year, salted meats, cheeses, winter vegetables, fish when the boats can put out. We don’t go hungry, probably never did given our local climate and the sea, but it was never easy and pretty monotonous.”

“How’re you feeling, the boy? Martha says you are making a good recovery, but never stop asking questions, but can I ask some? Where’s your husband? Why do you think you ended up with us? Tell me about your life? You may as well rehearse it because you will have to tell your story many times now that you’re here.”

To her own surprise, she just dived in, wasn’t even derailed by her returning son who was beckoned into the kitchen by Martha and clearly distracted with slices of buttered bread. Her family and upbringing which, by how the crow flies, could only be a handful of miles away, but now seemed almost in another world, her parents, her education, her job, her husband and child, his profession. She hesitated, not knowing how to go on into deeply personal matters which, now that she had to explain them, seemed so small, so petty and so selfish. How to explain why she had left home? Had she really left him?

“Go on Sally.” He smiled at her. “There must be more, otherwise you couldn’t have found us, wouldn’t have made it through the barrier.”

She looked at him. His blue eyes, wrinkled brown skin at the corners. He might have the manner of a naturally shy, old fashioned rustic but she could see the keenness of perception there, perhaps a wisdom. How to open her heart to a stranger, even one who had rescued her and taken her into his own home and treated her only with kindness? Her loneliness had made it impossible to speak to anyone about these things, even her parents or so-called friends, let alone Andy.

“If you tell him the rest we might be able to help you know.” Martha had re-entered the room, bearing what looked like a bottle of cider and three glasses. She filled them, offering one each to her husband and guest, “To your safe arrival, your health and happiness and for the gift of childish laughter in my home again.”

She went back into the kitchen, shooing Sally’s son with her. Sally took a deep breath: there was more tenderness in this house of strangers than she had experienced for a long time; it was a matter of faith, of trust and she, almost heedless, chose to trust. Out it spilled, disjointed, discursive. Her husband’s growing pre-occupation with his career, his hardening in response to the things he had to cope with, her increasing loneliness and isolation in a huge city which became ever more alien, her retreat to her childhood faith and the wedge it drove between her husband and herself, the pouring of her energies and emotion into her son, her growing sense of being adrift, what she had thought she was doing when she had left home only the previous day. She stopped, surprised at her almost complete unburdening, ashamed of how trivial it must sound to a stranger. And he had just sat there, quiet, attentive, just soaking it up, not questioning, not commenting, just looking at her gravely as if trying to convey sympathy through his stillness.

“Do you still love him?”

“He’s my husband and I don’t want a divorce, there’s Josey to think of…”

The question had been gently put, but puncturing in its directness.

“That’s a legal and spiritual state. Do you want to be with him again?”

“I don’t know, I suppose…”

“Well there’s no rush, I’m blessed never to have experienced what you have, but it might matter a lot… to the shape of your future. You say he’s in the Counter-Terrorism Command, a senior officer? And you were in the Foreign Office and speak fluent Italian and know Latin? Yes? You also know some other languages, not so well, but French and Spanish? Greek?”

“GCSE Ancient, a bit at University, but not since and that was a long while ago now.”

“Mmm, could be helpful.”

Martha called them through. He relaxed. “Very few come here entirely by chance and even fewer bring children. We are truly fortunate today. It’s your turn to ask the questions over dinner, after you.”

The two vans came off the M42 and pulled up the slip road signed for the NEC; despite the loss of the missing Badr and their martyred brother their alternate target was almost as glorious as their primary one. A convention for the senior officers of the world’s largest spirits multinational, nearly 500 in all, was taking place at one of the hotels on the site. Even better, their wives and husbands, politicians including a Cabinet Minister, an Opposition would-be minister, bankers, diplomats and major customers would be there for the dinner and entertainment, after a hard day’s planning how to corrupt the youth of the world. Well over a thousand people in all. Abdul Patel and his seven fellow martyrs were going to put Mumbai in the shade. One of them was already working in the kitchen. Security would be tight but discreet, and certainly not prepared for what was coming.

Abdul smiled to himself as they paused outside the car park. A couple of guards on the barrier, one police and the barrier operator, a couple more police patrolling outside the dining room and ballroom where the main event was in full swing, others inside by the lobbies, just as they expected. The explosives were to be primed for contact detonation when the two suicide drivers hit the main entrance and the dining room side fire exit, the brother on the inside would blow the back lobby, and then he and the other brothers, having dismounted as the vans came through the barrier, would get into the remains of the hotel and cause mayhem with their AK47’s and knapsacks stuffed full of ammunition and grenades. They were not coming out, but would take hundreds more infidels with them.

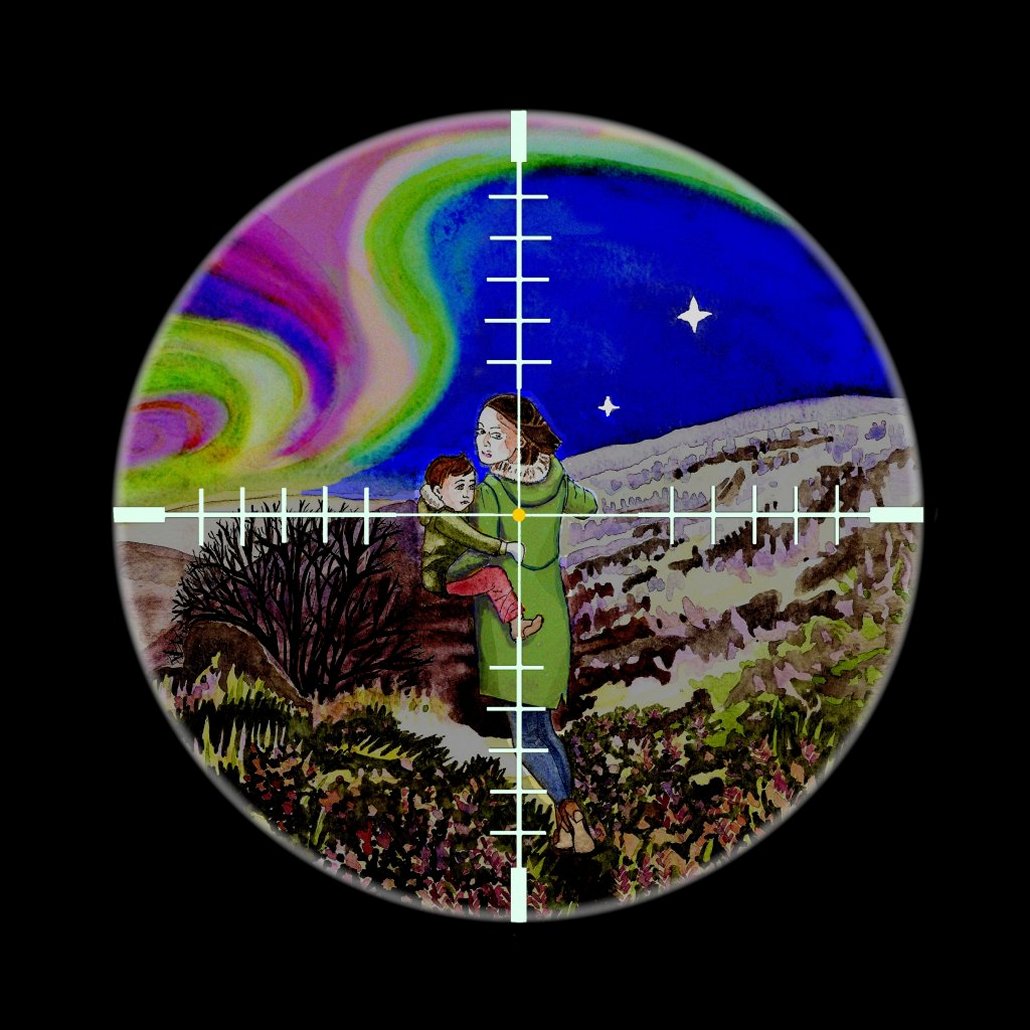

Their vans came on again, slowing just before the last but one roundabout before the car park entrance. Suddenly, without warning, the windscreen shattered with a scream as he and the driver beside him were riddled with bullets. Can see nothing, feel little, can’t move, ambush… Just fire behind, those in the compartment and van behind, dozens of rounds impacting, the shooters must be in the car-park on the other side of the entrance road… Then nothing at all, at least nothing earthl

© 1642again 2018