You may remember some months back I related a story of my first fire exercise sailing under the Red Duster. I was somewhat unimpressed having come from a different seafaring outfit where these things were taken very seriously, almost fervently so. So I thought I might tell the tale of another time I didn’t put the fire out the correct way.

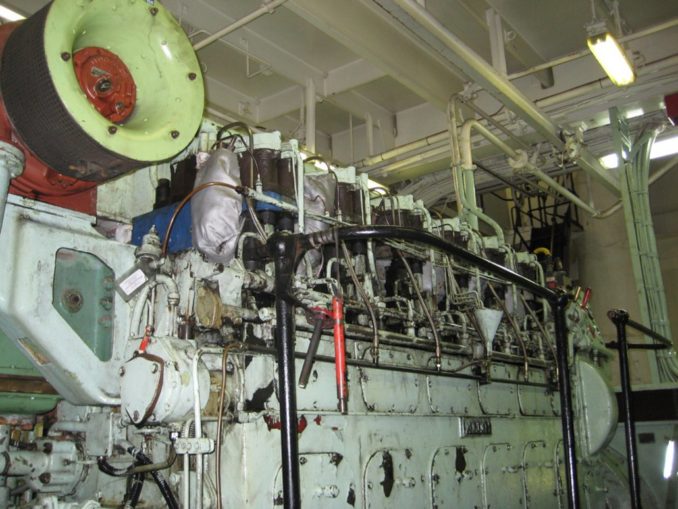

In Spring 2009 I joined the fleet tanker RFA Bayleaf in Cammel Laird’s shipyard in Birkenhead. Bayleaf was undergoing what would turn out to be her final refit. She was one of the “Leaf” class tankers, originally built as a commercial tanker but after her original owner fell upon hard times she was siezed by creditors and eventually acquired along with her three sister ships by the Royal Fleet Auxiliary. Bayleaf was always known as a real workhorse, which is a euphemism to say by 2009 she was totally shagged, and no refit was going to get around that. I joined her as a Third Officer, I was three years out of my cadetship and this was my third appointment as a qualified Engineer Officer of the Watch. The particular billet I had saw me as the 12-4 watchkeeper and I was also directly responsible for the maintenance of fresh water production and the domestic fresh water system, the oily water separator and bilge system, air compressors and compressed air systems, and crucially for this tale, boilers and steam systems.

It would have been sometime in late spring or early summer that we left Cammel Laird and embarked upon sea trials, which if memory serves were every bit as eventful as I expected. I remember the Chief Engineer, well known in the service, a man of immense experience and perhaps the best marine engineer I ever sailed with, remarked to me one day with a wry grin that “Leaf boats are character building.” Well Bayleaf was the most character building of the lot. She certainly knew how to show the engineers a good time.

After sea trials we ended up at the NATO fuel jetty in Loch Striven. A wild and lonely place…. Our purpose there was to load a cargo of diesel oil (aka NATO F76) and aviation jet fuel (aka Avcat or NATO F44). Once we had filled our cathedral like cargo tanks with the stuff we would head off into the wild blue yonder and be a giant floating petrol station for steely eyed men on their sleek, grey war canoes.

However, before loading the cargo there’s something quite important we have to do first. Clean the cargo tanks. The Leaf tankers were fitted with what was called a Butterworth tank cleaning system. This is a rotary nozzle which sprays high pressure water which washes down the interior of the cargo tanks. The water came from the ship’s fire main (which is pressurised to 10 Bar). To help things along the water is also heated to around 50 degrees Celcius. The heating occurs in the appropriately named Butterworth Heater, which is a large tube type heat exchanger in the Cargo Pump Room. The heating medium is the ship’s cargo steam system.

That’s where I come in.

Tank cleaning takes most of the day, and the loading of cargo is a major operation which could take two to three days. The programme is set, the relevant people shoreside are made available and nothing must be allowed to delay the loading of cargo. As such the tank cleaning process is very important and it’s vital that everything goes to plan so the loading of cargo can commence on time.

On the day I set my alarm extra early and was down in the engine room by 0600 to flash up the cargo boiler and have the cargo steam system ready for the scheduled start for tank cleaning at 0845. At this point I’d had several unfortunate water related incidents in the previous weeks. I’d had the auxiliary boiler hotwell overflow several times due to an intermittent fault on a float switch. The first time I’d flashed up the cargo steam system to prove it I’d overflowed the cargo boiler hotwell *big time*. The problem was as the system is cold the first returns are a giant slug of condensate which the hotwell can’t cope with and overflows (any steam engineer puffins are laughing at me now, but in mitigation I’m a clanky, not a steam queen). Finally, before leaving Cammel Laird I was instructed by the Executive Officer to fill the stern peak ballast tank. When I traced out the filling line I found it had been spaded (blocked off). Nobody seemed to know why this was the case and it looked to have been done a long time ago. I erred on the side of caution and decided not to use the filling line. Instead I’d remove the manhole cover to the ballast tank, located in the steering flat. I would then use a fire hose connected to the fire main to fill the tank. I calculated it would take about two to two and a half hours to fill the tank by this method. I rigged the hose, lashed it to the access ladder for the tank making sure it was pointing down into the tank. Then I went and opened the fire hydrant a bit. Everything looked good, so I went back and opened the hydrant up fully. At this point the increase in pressure in the hose made it turn and point upwards, out of the tank and instead of filling the stern peak tank I was instead filling the steering flat.

After these water related incidents my shipmates had taken to calling me Patrick Duffy (The Man From Atlantis). The engine room petty officers were especially merciless.

However, this day I was determined would go by without any watery incidents. I planned to flash up the cargo boiler and raise steam with the boiler open to the cargo steam system. This would slowly warm the entire system up simultaneously and I wouldn’t end up with a massive slug of condensate returns from the cargo steam system overfilling the hotwell and making me look like an idiot (again). It took a couple of hours to slowly warm the boiler up and start to raise steam, but by 0800 I had the system up to the normal operating pressure of 10 Bar and everything was running very nicely indeed.

The next step was to get a fire pump running (remember the Butterworth system has its water supplied from the fire main) and check the water from the Butterworth is nice and hot. The fire pumps on a ship are usually very big and very powerful. After all, they’re meant to shift plenty of water for putting out fires. Big centrifugal pumps like these consume a lot of Amperes. The Leaf class had two diesel generators each rated at 625KW and two main engine driven shaft alternators each rated at 2.5MW. The diesel generators were normally used in port and for standby conditions at sea, and the shaft alternators were used for cargo operations in port (required for powering the very big cargo pumps), and normal underway conditions at sea. If we were running on the diesels it was normal practice to make sure we had both generators running before starting a fire pump because the load was so high. The problem was the port diesel generator had developed an oil leak overnight which was bad enough that we couldn’t ignore so had to do something about it immediately. We couldn’t delay tank cleaning either as that would have a knock on effect for cargo loading. It was decided if we carefully managed the electrical load on the ship we could carry out tank cleaning on just one diesel generator, although we wouldn’t have much spinning reserve (i.e. electrical wiggle room). The Duty Engineer Officer (not me, for once!) was instructed to monitor the electrical switchboard closely and keep an eye on the total electrical load on the one running generator. My job was to keep an eye on the cargo boiler and maintain sufficient steam pressure for the Butterworth to do its thing.

By late morning things were going well. Tank cleaning was progressing at a satisfactory pace and “my” boiler was keeping up. The load on the starboard diesel generator was about as close to the bloodline on the gauge as I’d ever want to see. The cargo boiler, however, was starting to run a bit low on fuel so I thought I’d better transfer some fuel from the bunker tanks up to the boiler fuel tank. This involves lining up the system (i.e. configuring the correct valves), starting the transfer pump and stopping it when the boiler fuel tank reaches 90% capacity. Normally I’d line up the valves, start the pump, check the fuel is going to the right place and there’s no leaks then I’d retire to the Control Room and monitor the level in the boiler fuel tank on a remote readout from the tank gauging system. Now a golden rule I was taught as a cadet is when you’re transferring fuel you do NOTHING else. You sit there and watch the numbers slowly creep up until you’re done then you go and shut the system down. Getting involved in or distracted by anything else risks you overflowing the fuel tank and causing a fuel spill, which is very bad news. On this day the remote readout wasn’t working in the Control Room, there was no signal being received from the master gauging system which was located in the engine room. In which case I’d have to use that instead. After lining up the system and getting the transfer going I went and stood next to the master tank gauging unit. This was located on the engine room middle plates forward. The transfer would take about twenty to twenty five minutes. I started pacing back and forth across the middle plates by the cargo pump motors. Occasionally I looked up and across the tops of the main engines to the generator flat which was in the after part of the engine room. I could see one of the other engineers diligently working away swinging spanners on the generator with the oil leak, his ear defenders clamped firmly over his lugholes whilst the other generator behind him was screaming its mammary glands off. Back and forth I went, watching the number indicating the volume of fuel in the boiler fuel tank slowly creep up. I glanced up again across the main engine tops towards the generator flat. The other engineer was still there, still swinging his spanners working on the oil leak. He was totally oblivious to the fact the starboard diesel generator behind him was on fire. Bright orange flames licking out of the top of the prime mover.

A thought entered by head. Can you guess what it was?

FFFFFFFFFFFFF…….!

It’s something of a cliched joke among marine engineers that when asked what steps one would take upon discovering a fire in the engine room the answer given is “fucking big ones”.

Suffice to say in this moment the veracity of this advice suddenly gripped me and I started taking lots of fucking big steps.

The training given in the RFA (and the RN for that matter) is the priority is to raise the alarm. Let the rest of the ship know. Then you grab the nearest firefighting appliance and maintain a “continous aggressive attack” on the fire until relieved by either the Duty Watch (in port) or the Sea Standing Emergency Party (SSEP) at sea. I hit the emergency stop on the fuel transfer pump and started running down the starboard side of the engine room to the generator flat, hitting a fire call point on the way. This will start the bells ringing all over the ship and result in an immediate emergency stations muster. As I rounded the corner and the fire came back into sight I saw the other engineer had noticed the fire burning about 5ft behind him and was powering up the ladder to the Control Room (to raise the alarm). However, by this point the bells were ringing everywhere and as I glanced up the ladder to the Control Room door I saw the face of the Duty Engineer Officer looking back down at me with eyes as big and round as saucers. Now, if you’re in the machinery spaces on an RFA (or HMS) you’re never more than a few paces from some kind of firefighting equipment. I grabbed an AFFF (Aqueous Film Forming Foam) extinguisher, dropped to one knee (just as FOST tell you) and started putting foam onto the fire. Those puffins who have had the pleasure of FOST will know that a 19L AFFF extinguisher gives you 38 seconds of foam. Just as those 38 seconds passed and my jet of foam turned into a dribble a hand grasped my shoulder. I turned around and the MEO (my boss) was stood there and handed me the branch and nozzle for the 150L portable AFFF appliance (basically a giant AFFF extinguisher). I glanced past him and saw every single engineering officer and petty officer on the ship pouring down the two ladders from the top of the engine room like someone had told them there was free beer on offer. Even the Chief Engineer appeared rapidly descending the ladder. Every one of them had brought some kind of extinguisher or firefighting equipment to the party… just as FOST tell you to do. The Duty Engineer Officer had appeared on the port diesel generator and was frantically working the controls to get it fired up and on the board so we could shut down the burning generator (the other engineer had just completed his work on the oil leak when he noticed the fire behind him). All of this within a minute of me hitting the call point to raise the alarm.

Fortunately the one AFFF extinguisher was enough to put the fire out but I was left to act as a fire sentry for another 15-20 minutes or so, with what appeared to be every fire extinguisher on the ship to keep me company. At this point one of the engine room petty officers, a piss-taker and wind up merchant of some renown popped down to ask Patrick Duffy if he was fed up with getting water everywhere and had moved on to foam instead.

Damage to the starboard diesel generator was minimal. It was determined the exhaust cover, which was fitted with lagging pads had been removed from the generator during the refit and left on the deck next to it, where oil and fuel had spilt onto it and soaked into the lagging pads. With the generator running at such high loads the exhaust had got hot enough that it had ignited the impregnated fuel and oil.

One other thing came out of the incident. In a harbour fire the Duty Watch are to go to the scene of the incident and start taking the necessary action whilst the rest of the ship’s company muster at the gangway and await tasking. None of the engineer officers and petty officers went to the gangway, they all went straight to the scene instead to assist in tackling the fire.

Zis ist not ze correct vay!

The Executive Officer was most miffed at this. I suspect in fact he was rather jealous at how swiftly and effectively the engineering department dealt with the emergency without ever needing any input from his own department. In order to ensure everyone is made fully aware of the correct procedure, and of course to stamp his own authority on the matter, he arranged for a harbour fire exercise, featuring an MMSF (Main Machinery Space Fire) for 1645 on the day cargo loading was completed.

However, once all the inter-departmental dust had settled I did get a pat on the back and a BZ from the MEO, Chief Engineer and even the Old Man himself “for my quick and effective actions”.

And that, was my first “real” fire. Don’t worry, I did put one out the right way a few years later, but that’s a story for another article.

All told I sailed on the Leaf class five times; as a Cadet on Brambleleaf in 2005, a Third Officer on Orangeleaf in 2008, a Third Officer on Bayleaf in 2009, back to Orangeleaf as a Third Officer in 2011 and again in 2012 where I was promoted to Second Officer. The Leaf class remain my favourite ships. They were old and knackered and disaster often seemed only a few moments away a little too frequently. However, they always seemed to have an absolutely tremendous crowd on board and they hold many happy memories of much laughter and shenanigans, friendship and camaraderie.

As that Chief Engineer said….. character building.

I remain grateful I had the opportunity to sail with such excellent people and to have called them my friends, and I am both honoured and humbled that they counted me among their number.

The fate of the Leaf class?

RFA Brambleleaf (ex-Hudson Cavalier) – retired 2007, scrapped 2009

RFA Bayleaf (ex-Hudson Progress) – retired 2011, scrapped 2012

RFA Orangeleaf (ex-Balder London) – retired 2015, scrapped 2016

There was also a fourth – RFA Appleleaf, ex-Hudson Deep. Appleleaf was sold to the Royal Australian Navy in 1989 where she was renamed HMAS Westralia. In 1998 Westralia had a major engine room fire which resulted in the deaths of three crew. In 2006 Westralia was decommissioned and sold off to a commerical outfit who renamed her Shiraz and used her as an FPSO vessel until she was laid up in 2009 and finally scrapped in 2010.

In fact, speaking of the Westralia fire… a year or two before a similar fire happened in Bayleaf’s engine room when a fuel injector pipe failed and sprayed high pressure fuel on a hot exhaust pipe. The initial fuel fire was quickly extinguished but a secondary fire started when the thousands of instrumentation and control cables routed on the engine room deckhead above the main engines ignited. I’m told it took over six hours to extinguish the fire during which time fire teams were rotated into and out of the engine room to maintain the continuous, aggressive attack on the fire. When they came out of the engine room they were sent into the ship’s deep freeze (normally kept for meat provisions) to cool down, get some water and have an air bottle change and a breather before they were sent back in to relieve the other fire team. Very scary stuff to contemplate and underlines the fact when you’re at sea you can’t count on outside help and the ship’s company have to be competent and able to deal with any emergency or crisis they encounter.

Oh, and if anyone is wondering about Oakleaf, yes she was around in the same timeframe as the ships I’ve just mentioned, but she was a totally different and unrelated class. Very popular ship to sail on in the RFA by all accounts and I regret not having had the chance to sail on her before she was retired.

I’d like to dedicate this article to the memory of Third Officer S C. We were both engineer cadets at South Tyneside College at the same time 2003-2006. Our paths crossed again in 2014 when we sailed together on RFA Fort Victoria where we shared both tears and laughter. We both left the RFA in 2015 for much the same reasons. S C passed away suddenly and unexpectedly in February 2017 at far too young an age.

You’re very much missed by many pal. Finished with engines.

© Æthelberht 2018

Audio file

Audio Player