Helena struck him once more as being really quite remarkable, just when you thought you might have seen all she had to offer, she revealed another new facet, maybe one unknown even to her, almost a lifetime’s study in her own right. He asked her to turn the music on, not full, but loud enough. Bach, Brandenburg Concertos, she knew he liked them, kept them at hand. The kitchen extractor was going, whirring away. He started the microwave under the oak counter and dimmed the lights as if planning to seduce a lover. The blinds were down. “Just habit, almost nothing to worry about.”

He pulled something out of the bag that had contained the flowers. A small folded freezer bag, wrapped in a rubber band containing some smaller items shielded from her sight by his hands. “They recovered these from a house in Birmingham. You’ve probably not picked it up on the news: they thought it a gas explosion at first, that’s what the press reported, but now they know better and it will be public domain shortly, I’m sure. That’s why they had to go back, take a massive risk to recover these.”

He was holding a number of memory sticks. “They could be essential, we need to know what they contain but don’t have the resources, skills ourselves. I’m amazed he had them in his house, it was complacent of him. You might… your line of work… decryption? But if you can help; we can’t read them, there could be two, three, maybe more levels of cipher; not straight forward.”

“How soon?”

“As soon as… If there’s anything there its value could fade faster than those daffodils I bought you. You know how it is better than I do. But one thing, security is absolutely paramount… Don’t take it on if there is the slightest risk of compromise. Please?”

He looked at her straight in the eyes, as if pleading with her to refuse it, but impelled to ask to satisfy someone else. Yes: there was a touch of emotion there, moisture behind the eyes she thought. Yes: the crack into which she had inserted her crowbar earlier was still there, had not resealed this time.

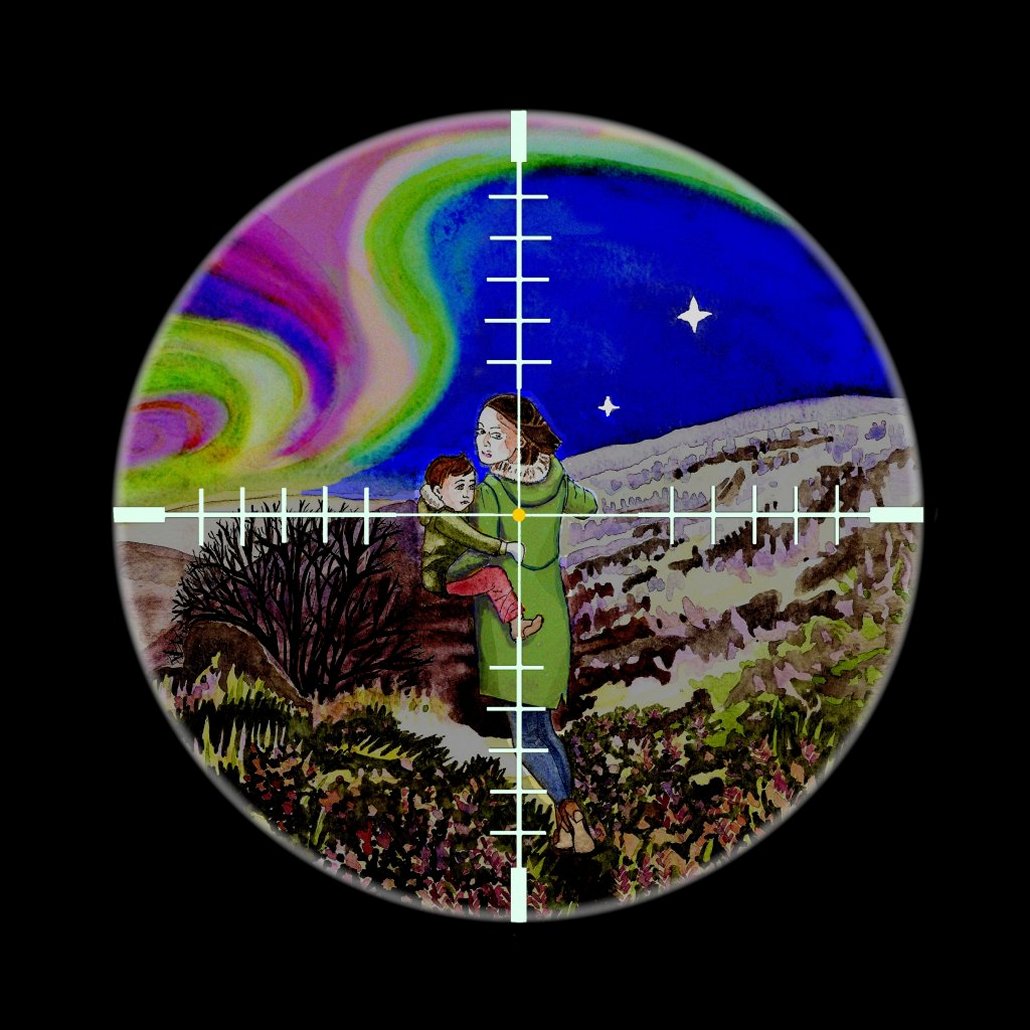

She sipped her drink and thought. Her world was full of secrets, confidences, all challenges to be mastered, learnt. Discovering others’ secrets was one of the ways you stayed ahead, usually by cultivating indiscreet sources, nice dinner, few drinks, unspoken promises of favours to be repaid in future, that was the currency. But sometimes, perhaps when the quarry was openly fleeing, when the competing wolf-packs were chasing it through the woods seeking to find it first, perhaps then higher risk approaches could be justified. Certainly illegal, but hard to discover if you were careful, knew the right people and could trust them. Most of the best players did it; it was an unspoken consensus, never look a gift horse in the mouth, especially if you could steal it away at night leaving no one the wiser.

There was someone she used from time to time. Cash only, expensive, eccentric, but hadn’t let her down yet. She had known him, them, for five years, they saw things like this as a technical challenge of expertise, not really interested at all in what they uncovered. It’s why she liked them. And they were flexible and understood the need for immediacy.

“There’s someone. They can be trusted, very good at what they do. I wouldn’t use most of them for this; you know the ex GCHQ and NSA ones who realise they can make far more money outside and not have to call people sir?” He grinned; it wasn’t quite like that, he knew, but he could see what she meant. “These are a bit more like the ones who stay in, almost a bit autistic, eccentric, out-of-their-depth in the real world. I believe that sort tend to be the best at this line of work? Well he’s self-taught, a bit of a loner, lives in a remote cottage in the wilds of the Lincolnshire fens, so he won’t be on the official register; at least he’s says he isn’t and he hacks in regularly to check. He’s got a daughter, just lives with her I think. He wouldn’t send her to school, said he distrusts official education as brainwashing. He seems to leave his tinfoil hat at home though and is not obviously nuts, just eccentric. She’s a nice girl, bit different, but that’s hardly surprising. Must be seventeen now. He says she’s as good as he is and will be better.”

“Are you sure you can trust them?”

“I’m certain I can. They bring two customised laptops, no external wifi or other connections. Just cd’s and sticks. No smart phones, just simple old-fashioned pay-as-you-go phones which they constantly change. They will work here as long for as it takes, don’t trust offices apparently, finish the task, give me the results on a stick with another copy, wipe and smash the hard drives, and leave everything, computers, the rest, for me to dispose of. They take nothing back, other than the payment, obviously. Very thorough and they don’t ask questions: he sees it as undermining the system. If we can trust anyone, it’s them.”

“Sounds expensive, that sort of thoroughness, how much?”

She wasn’t sure, but gave a range. He winced. “They’ll be worth it; they could get more if they could be bothered to negotiate. It’ll be half in cash, Sterling and Swiss Francs, and half in gold coins, Sovereigns, Britannia’, Krugerrands, that sort of thing. He says he plans to buy an island somewhere in the South Pacific off the map, sail there in his own yacht and disappear; she never says what she wants, but seems to adore him. As I said, a bit eccentric but reliable, trustworthy and very good.”

“When could they start, sometime next week?”

She smiled at him. “That’s the best bit, if they take the job I should think they’ll be here tomorrow morning knowing them, for me and for a bonus of course. And don’t worry; I have that sort of funds in the safe here. You never know, he may just be right about the banking system as well.”

His face was beaming at her now with the glow of admiration. She basked, it was nice to surprise him occasionally. He came up and stood before her, and gripped her elbows in his hands. “I just don’t know what I would do without you.”

She went to make the call; he insisted she use one of his own disposable ones, while he prepared the salad and laid the kitchen table. She seemed to prefer entertaining him in here, as if it helped her complete the making of a dwelling into her home. By the time she returned he had even got the cottage pie out of the oven and begun serving, “Sorry, I’m famished, been out all day, and besides you’ve done the hard work.”

She smiled. The man and daughter would be here at ten thirty tomorrow, that’s all, hadn’t asked any other questions other than agree the fee. He seemed so at rest here. She asked him the news, how they had fared, what they had done. He owed her the truth he decided. So out it spilled, the risks, the complications of the girl and arriving policemen, she had shuddered at the passing mention of the killings, the getaway. “Are they safe now?”

“Pretty much, should be at the final staging ground tonight, then the last step when clear to go. They won’t take any risks now. The policemen are ok; bit battered and deafened, but will know they were very lucky. The girl they’re taking with them, we have no idea what to do with her. No, don’t worry, they’re not like that. It’s a distraction I don’t need, we’ll try to find a way to get her home safely, but it won’t be quick or easy.”

And then they had rattled on. Wait until the end of the meal, then start, gently, but don’t get distracted. He knows he’s in your debt, heavily. Ice cream out softening, main course put away…

“I’m not sure she would like me any more you know.”

Sudden, out-of-the-blue, where the hell did that come from? He was looking over her left shoulder, beyond the cupboards and wall six feet behind her. “If she knew, knows…”

He seemed to be waiting for her to fill the void. She’d been preparing, had thought it through, had already found the purchase point earlier, that little crack to open up, gently, tenderly, to get to what she craved inside: him. So seldom did he open up, so precious the moments. Yet suddenly, now, here, totally unexpected and unplanned, complete self-exposure and almost helpless vulnerability. Utterly disarming; the urge to mother, to defend him was over-powering her own plans, casting them aside like dross into the pit. “I never knew her, you know that. What do you want me to say?”

Had he ever spoken like this before? No, sometimes close, very occasionally, but no, not like this. No answer, just that continuous stare into the middle distance. “Why do you say that as if you have done things you should be ashamed of?” She was getting upset with him now. “Why do this to yourself? I’m sure she would understand, support you, and continue to feel the same way, as I do.” There, it was almost out, in the light, but still timid. “You do what you do for others, not yourself, to protect them, that’s what’s important. Sometimes we all have to do hard things, so long as the intentions are good, that’s all that matters.” Who was she talking to, him or herself now? “You know the story of the widow’s mite? That’s you. That’s one of the things I…”

Edging back into the dark of the cave now, terrified of the noonday sun’s pitiless light. “They, those men, they help you, risk everything. What for? Why? Because of you. They share the goals, the same motivations, sure,” well as far as she knew, “they wouldn’t be there unless for you. They went back twice, unprepared, volunteered because they believe in you. She’d understand, not even see a need to forgive.”

His eyes slid back gently on to her. “That’s what makes it harder; what if I… we, are wrong, arrogating things that aren’t ours to decide?”

It was like watching a fish twisting on the end of a line being reeled out of the water, struggling to-and-fro in its efforts to escape the hook, but only impaling itself all the more deeply. The irritation was rising again; she was unused to this self-pity. “There’s no easy answer, you knew it when you chose to start, but you can’t give in to self-doubt now you’ve got them to do the things they’ve done for you. I thought you might be mad at first when you told me, you know? I supported you because I believed in you, for no other reason, and now I see you were, are, right, as they do. You owe it to them, us, me… I’ve not seen the things you have, I’m pretty sure I would never want to. She saw far more of them than me, much more, more maybe than you, but from what I know of her from you, she would still love you… even more.”

He looked at her, smiled, the worries suffusing his face receding back to the very corners of his eyes, where they remained, largely sheathed, only their sharp cutting tips peeking out. “Thanks, whatever would I do without you; you’re my best friend you know, I’m not sure I’ve ever told you? Now what do you want to talk about?”

“Later, after dinner, now, pistachio or almond?” Coward, but she needed a pause to regroup.

Andy Bowson, if he had been offered ice cream, would have cheerfully thrown it at the wall of the ward which was now feeling like a prison. The frustration and waste of it. Commencing with the day that was the downer of Dager’s morale raising visit, then other visits, official and social, fellow officers, mainly locals; he had then been asked if there was anyone he needed to contact, his wife maybe or his parents. Edward had made frantic dissuasive gestures at the well-meaning nurse who put the question, but the damage was done and his ill humour magnified three-fold. His own parents were gone, his sister on the other side of the world. What about Sally’s parents? They had enough to worry about, he would call them tomorrow. What about his wife, well what about her?

He asked to call the local case officer who had given him his personal number with the offer to ring him any time. See if he was serious, call him now, Saturday dinner time. Surprisingly the phone was answered and he was asked if he were alright. He explained. Long silence followed. The man was solicitude itself, relayed his best wishes and then explained progress, or lack of which was much nearer the truth, and then tried to confer a positive and hopeful spin on things, presumably for his sake. To be fair to him, he didn’t try to get him off the phone, but explained how they were expanding the search radius on the moor, more locals were helping, and a couple of local amateur pilots were combing the ground to relieve the police helicopter. But he couldn’t disguise the fading hopes or the fact that this type of intensive search tended to have a half-life of four or five days at most. Almost as bad, given Bowson’s state of mind, the scum who had done this to him had got clean away. The duty doctor who called on his rounds later that evening with an innocent comment about being lucky to be discharged before Monday at the earliest went off duty with a much lower opinion of the manners of senior police officers.

© 1642again 2018