Following the outpouring of joy over the street cars of Paramaribo – complete with a trip to Kabelstation (where a rope-worked gondola spanned the Suriname River), and a railcar ride with the Queen of Holland, one’s obliged to pop next door to another esoteric iron road stretching across the north coast of South America – while we still can.

As every Puffin knows, Guyana is defined by its three great rivers, the Berbice, the Demerara and the Essequibo. Lying to the west of Suriname (capital of which is Paramaribo), the one-time British Guiana is the size of England and Scotland combined, but enjoys a population counted only in the hundreds of thousands. Why so?

Impenetrable jungle and swamp, that’s why so. However, the coast could be tamed, and was, to grow sugar. Many of the resulting plantations joined by rail for the purpose of moving the commodity, as well as rice and people.

The first railway in South America was constructed there in 1848, a mere 23 years after Locomotion made its spluttering debut between Stockton and Darlington and a decade before the slow coaches in Africa built their first railway between Alexandria and Cairo.

That first line was the Demerara Railway, which connected the capital Georgetown on the banks of the Demerara River with Rosignol, 60 or so miles eastwards along the Caribbean coast to the banks of the Berbice. However, for no reason in particular, we shall head west and follow the alignment of the Demerara to Essequibo Railway, which operated from the 1890s.

At this point of our research, we must be careful, as another Demerara to Essequibo railway up country hacked its way through tropical woodland to connect Wismar on the Demerara to Rockstone on the Essequibo. Back on the coast, we shall start from the west bank of the Demerara, a bit more than half a mile by ferry from Georgetown’s Stabroek Market on the opposite bank.

© Google Maps 2025, Google licence

Here sits Vreed-en-Hoop, where we begin our 14-mile trip to Parika on the banks of the Essequibo, the longest river in the Guianas and the mightiest waterway lying between Venezuela’s Orinoco and Brazil’s Amazon. Features up country include the Kaieteur Falls and, as it reaches the Atlantic, the Essequibo islands – more of which later.

Closed half a century ago, the permanent way is not in place, but the route can be followed via the obvious shallow curves of rail alignments. The occasional old railway bridge, canal abutment or row of telegraph poles guides us on our way.

Starting at Vreed-en-Hoop and heading west, it’s easy to see where the railway lay. If we zoom in, the alignment is next to a canal and bordered by shadows cast by telephone poles. The land is flat, allowing for residents’ strip farms and, at the bottom of image one, for sugar fields and their associated canals, running on our horizontal towards the Demerara. At the top of the picture, an ominous grey blob is being reclaimed from the sea – more of which later.

A mighty curve follows the coastline and, as it does so, it crosses the main road from where the Google Street View car can do a job of work for us. First, we look east, back towards Vreed-en-Hoop, with the railway running between two rows of electricity and telephone wires next to a canal. A rough roadway sits upon the route to the other side, in the direction of Windsor Forest.

© Google Street View 2025, Google.com

A rough roadway sits upon the route to the other side, in the direction of Windsor Forest.

© Google Street View 2025, Google.com

Below, the line nips the coastline before Windsor Forest before moving inland towards Den Amstel. Why these strange names? Because they originated from the peripatetic planters all those years ago.

© Google Maps 2025, Google licence

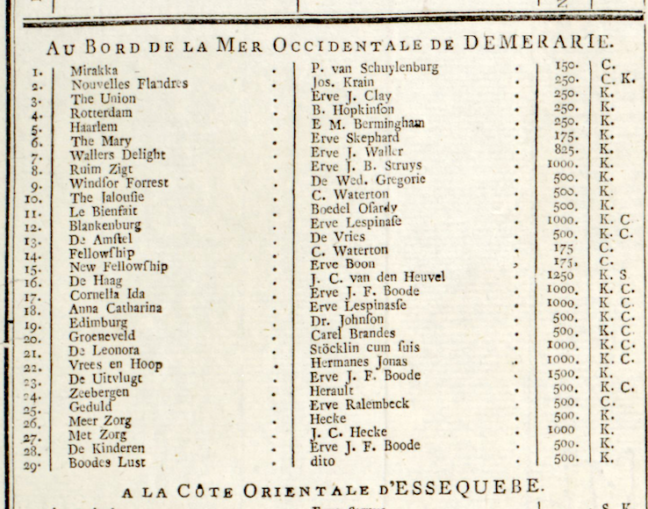

I’m indebted to Major F. von Bouchenroeder, who mapped and numbered stakes in 1798. However, being foreign, he did it upside down and the wrong way round, and used pre-metric local measurements, having made his map on behalf of the Batavian Republic.

What is that, you ask? The successor state to the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands and the predecessor of the Kingdom of Holland. In other words, this coast belonged to the Dutch, with a tug of war resulting in the territories being ceded to Britain in the Treaty of London of 1814. Von Bouchenroeder’s (rotated) map:

Carte Generale & Particuliere de la Colonie d’Essequebe & Demereraire,

Major F. von Bouchenroeder – Public domain

According to his index, Windsor Forest is number 9, is owned by Gregorie De Wed and covers an area of 500 ‘carreaux’ or ‘squares’. De Amstel is number 13, is owned by the De Vries and covers 500 carreaux. The mixture of Dutch, English and Spanish names suggests a bit of a free-for-all during the establishment of the sugar industry.

Carte Generale & Particuliere de la Colonie d’Essequebe & Demereraire,

Major F. von Bouchenroeder – Public domain

Of course, in the 1790s, the lion’s share of the hard work would be carried out by another nationality – Africans held in slavery. With the slave trade being abolished in the British Empire in 1807 and slavery in 1834, such things were over by the time the railway arrived. But the database of compensation paid to slave owners upon abolition proves insightful.

The Vreed-en-Hoop plantation belonged to a Glasgow merchant by the name of John Gladstone. With 472 slaves, he received an astonishing £22,000 in compensation, the equivalent of £3,000,000 today.

Indentured labour replaced slavery, a system whereby a person was contractually bound to work without a salary for a specific time. In those days, this arrangement was often used to repay debt or to cover travel costs for a new life in a colony. This takes us back to Windsor Forest, which became the first Chinese settlement in Guiana in 1853 when 105 indentured labourers from China arrived on the Glentanner.

For the technically minded, our friends at International Steam tell us that between 1897 and 1900, the Demerara Railway Co. built a 15-mile-long 3’6” narrow-gauge line between Vreed-en-Hoop and Greenwich Park. In 1914, an extension took the railway 3.5 miles to Parika, allowing for connections by ferry.

There were six intermediate stations and numerous simple halts with, from Parika, river steamers connecting with Leguan, Wakenaam, Supenaam, Arura, Adventure and Bartica. In 1922, the Government line acquired the line, and the following year carried 269,000 passengers and 4,500 tons of mixed freight (sugar and molasses from Leonora and Uitvlugt estates and rice). In 1962, it carried 500,000 passengers. It survived the ECR by at least two years, as it was still operating in 1974.

Back in the present day at Leonora, the alignment is well south of the road, with Station Street and Line Top Road being giveaways, allowing us to plot the route. Again, to the left, are sugar fields.

© Google Maps 2025, Google licence

By now we are at De Kinderen, and according to von Bouchenroeder, we are next to the Boerasirie River. This survives, as do the place names on the map, with De Kinderen on the right of the river being 500 squares owned by Erve J. F. Boode in the 1790s.

© Google Maps 2025, Google licence

The Boerasirie necessitates a larger bridge crossing than the earlier canal abutments. A truss bridge is still in place and visible from the main road.

© Google Street View 2025, Google.com

After Tuschen, we are not following the coast, but rather the east bank of the Essequibo. As such, we must turn a page on the major’s map for the final leg to the jetties at Parika. Although away from the road, it’s easy to make out where the railway went due to its curves and two lines of foliage adjacent to a canal.

© Google Maps 2025, Google licence

At Parika, which we will assume to be the old map’s ‘Parica’, we are on the one-time property of John Daly. There is a John Daly of those times mentioned in despatches as one of the principal proprietors of land in Demerara in the late 18th century, with an annual income of between £20,000 and £30,000, a whopping six million in today’s money.

According to Mr David Alston’s research on Highland Scots, enslaved Africans, and the plantations of Guyana, in 1798, Daly presented a memorial to the government in London in which he proposed the creation of a force of ‘disciplined mulattoes’ to protect the colony. In 1799, he was living at Cobbins in Essex but returned to Demerara in 1807.

The Saturday 21st February 1807 edition of the Essequebo and Demerary Gazette reported: ‘John Daly, Esq. a considerable Planter of this Colony, and formerly a Member of the Hon. Court of Justice, with his daughter-in-law Miss St. Felix, came passengers in the Planet. Mr. T. Engels and Mr. G. Luders were also passengers.’

Just the type who would own the plantation where the ferries left from! Although the railway buildings are long gone, the existing jetties still capture the atmosphere of previous ages better travelled.

© Google Street View 2025, Google.com

© Google Street View 2025, Google.com

While we’re in the vicinity, we must venture upstream to one of those Essequibo islands. Eight miles along the river from Parika lies the slender Fort Island. Contained within is a Tentative World Heritage Site. From one side of a modest jetty, we can walk to Fort Zeelandia, a brick fort dating from 1743 built by the Dutch to replace their earlier wooden fort of 1726.

© Google Street View 2025, Google.com

In the other direction sits the Court of Policy, the highest governmental institution in the Dutch colony. This dates from 1752. What an interesting place!

© Google Street View 2025, Google.com

But hurry, that ominous blob on the top of picture one is the Vreed-en-Hoop Shorebase, needed for the new and booming offshore oil industry. A new Chinese-built suspension bridge will soon replace the Stabroek ferry. Although much of Major F. von Bouchenroeder’s mapping is still recognisable, its days may be numbered.

© Always Worth Saying 2026