It takes a week to cycle from Penzance to Berwick. It took me 40 years. Because on the way, I wanted to include every town in England, in what amounted to some two years of day-rides. Most of these rides were point-to-point, but some were loops, and some looked on the map like a dropped noodle. It wasn’t a continuous line, but many separate lines, and all rides included towns I had not visited before. I used trains to get to starting points. Each ride had to be at least 20 miles, and in each new town, I had to touch a central feature, ideally the market cross or town hall. This is just one of hundreds of rides on this lifetime’s journey. A few more journey writeups can be found at my “Riding the Shires” website, from which this was taken, at Riding the Shires. Half a century of cycle-touring.

September 2024, Holsworthy: Before setting off for Barnstaple, this day’s destination, I had a good look around Holsworthy by daylight. It was a hilltop town; roads leading off the marketplace and its knot of Victorian streets sloped pleasingly down into stream valleys on every side. Small and nondescript it may have been, but Holsworthy was unusual for one thing, the size of its hinterland. For a great swathe of empty country, this was “the town.” That gave it a slightly more bustling centre than you might have expected, with at least half-a-dozen cafes, and a faintly detectable aura of local importance. With a population of just a few thousand, it even had its own drama group, the Holsworthy Amateur Theatrical Society.

An endless procession of agricultural haulage lorries and at least three large-animal vets showed clearly enough what underpinned its economy, though I did wonder where the model railway shop found its clientele. Did Devon farmers spend their Sundays in the attic recreating the lost Okehampton–Bude line, which in addition to the aforementioned bridge has left two intact viaducts nearby? It was thriving enough for some new housing to be under development on the edge of town; 30 units in one estate, which, in contrast to what’s being done to the rural Southeast, seemed a manageable addition to the local population. But Holsworthy hadn’t escaped the decline that now blights most English country towns. There were a number of recently closed-down premises in the centre.

On the way out, I passed the plant which is actually its main claim to fame these days, though I didn’t realise it at the time. This town is home to the only “centralised anaerobic digestion facility” in the UK. Which, in layman’s terms, is a plant that turns cowshit into biogas.

I left Holsworthy with a slight pang of regret, for I am fond of these out-of-the-way market towns where I like to imagine my England — the old England of conkers and train-sets, cycling proficiency tests, bob-a-jobbing, Green Shield stamps, Sunday roasts and penny-for-the-guy, shops with tinkling door bells, peas sold in the pod, dusty jars of gobstoppers, front doors you didn’t need to lock — somehow lives quietly on. There are, let’s face it, few other outposts left.

But it was good to be properly on the road again, carefree and without pockets full of wet pulp and a horrible clingy damp feeling all over my body.

It was nice too to meet some fellow cyclists. The first encounter was with a dawdling middle-aged trio, who drew up for a stand-in-the-saddle chat. They told me that Holsworthy is locally called “Olzery,”roughly rhyming to my ear with “hosiery.” My informant went red as a beetroot when I used that pronunciation myself while explaining my route; it was as if she had given away a secret code word. The two gents just laughed: “Much easier to say, isn’t it?” It was. One pointed at a place on my map called Woolfardisworthy.

“How do you reckon people round here say that?”

Probably not Wool-Fardis-Worthy, I ventured.

“Woolzery.”

There were a number of –worthies round these parts on my map, and also of places ending in –acott. Another local peculiarity was “Fore Street,” found in larger Devon towns, but not the same as High Street. I never did find out exactly what it meant.

The weather wasn’t great today either. Overcast and still, making for another rather lifeless landscape, without shadow or motion, seemingly frozen in the brief intermezzo between the full-leafed end of summer and the onset of autumn. The lanes were empty. Here and there, stilled windmills, those mammoth replicas of plastic fairground toys, emphasised the deadness of the scene and continually reminded me of a modernity I was keen to escape. My bike rides are always, in part, flights into the past.

It felt odd to be into the second day of a linear ride and still be in the same county. West Devon sounds so idyllic, doesn’t it, the place, you imagine, where the clotted cream is most clotted and the cottages most heavily bedecked in primroses. But inland I found it largely devoid of attractions. The granite-and-slate villages were nice but not ravishingly lovely; they were for farmers, not tourists or retirees, and were often dotted with rusting old tractors, rotavators and Yang Ming freight containers. (Just about wherever you go in rural England, no matter how pretty, you can count on finding a scrap-filled yard with a battered Yang Ming container at the back). There were no grand country houses, no castles, no ancient monuments, no dramatic outlooks and, for my money, surprisingly few enticing pubs or churches. It was just a rolling expanse of quiet pastureland, dotted by lonely farms and chapels.

I stopped at one of the latter, now a home, for a snack and a ponder. These old Methodist chapels were once the social centres of entire communities, the places where you went not so much to worship as to mix with other villagers and so find a job or a spouse. Historically, these parts must have been quite poor as well as isolated. Prices today were comparable with the South Yorkshire coalfield: a coffee was £1.50, a good breakfast five or six pounds. It seemed curious that rural Devon votes Conservative or Liberal Democrat, even though most of the population is solidly working class, engaged in farming, the trades, tourism and light industry. The difference with the Labour-voting north, I supposed, was the lack of large-scale unionised industry, though that’s just a guess.

Even in high summer, this area was quiet, I was told by a local cyclist who gave me directions. He was about my age, and was cycling mainly, he said, on doctor’s orders. He didn’t go into details, but he had to exercise his heart a little every day. When he asked me where I’d ridden from, I knowingly replied, with perhaps a hint of a West Country brogue, “Olzery.”

“Where?”

“Olzery. Written Hols-worthy. Pronounced Olzery.”

“Oh, Holsworthy. I’ve never called it Olzery. And I’m as local as you can get.”

“Oh …. Lucky you,” I rallied. “growing up amidst all this.”

“You know, I took the countryside for granted.” He paused reflectively. “It’s so empty. So much woodland around here, isn’t there, and nobody doing anything with it.”What’s wrong with it just standing there looking lovely? I thought. Isn’t that a contribution? Why does it have to be productive? Instead, I told him he should stay away from my old home, the Chilterns, as the acreage of useless trees there dwarfed West Devon’s. As a matter of fact, except in the steep, lush river gulleys, large woods had been few and far between on my route. Generally, this was copse and glade country.

But it certainly was empty. For fully five miles, I had no hamlets at all. I was aiming for a junction called Stibb Cross; my lodestar for an hour. Who, I wondered, had Stibb been – some highwayman gibbeted there perhaps? – and looked it up later. Of the various etymologies Mr Internet came up with, the likeliest seemed an Old English word for “tree stump or a place cleared of trees,” probably cognate with stub and/or stump. It was a suitably lonely spot.

Soon after came the village of Langtree and the day’s first church visit. All Saints stood squarely on a hillside, a Perpendicular church of granite with the grey hues of flint. Inside were old stall pews through which a fine arcade of arches marched, under a white barrel-vault ceiling criss-crossed by black lines, creating a fishnet effect; a fine late 17th-century carved pulpit and an intriguingly off-centre chancel arch set in a red-painted dividing wall. Altogether an unusual and striking interior.

And if all that’s a bit dry for you, let me refer you to the church’s own website for a more down-with-the-kids interpretation: “That chancel arch is fair bonzer though, plumply curving to the point, and that arcade is a beaut too. I have met many a worse, and not a lot better when we are talking granite.” That’s a direct quote, and there are paragraphs more like that on the homepage.

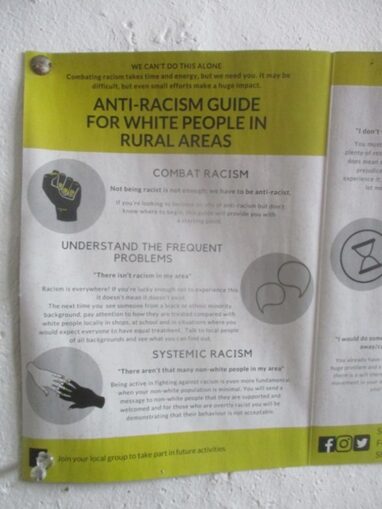

That was good for a laugh after the ride, but I left that church in anger, and, for the first time in my life, with an urge to commit an act of vandalism at a sacred site. Pinned to the porch wall was a notice that read, and I quote: “Anti-racism guide for white people in rural areas.” It went on: “The next time you see someone from a black or ethnic minority background, pay attention to how they are treated compared with white people locally in shops, at school ..” It wasn’t enough to not be racist. White Devonians needed to be actively “anti-racist.”

This was presumably written or endorsed by a local vicar, the same enlightened soul who commissioned or perhaps himself (or herself, or theirself) penned the fair bonzer website text. Stupidly, I forgot to get the name of the issuing organisation in my photo. But what an effing insult to the parishioners of Langtree, whose community, I suspect, contains almost zero immigrants. No wonder the church is dying when it’s full of sanctimonious wankers in dog-collars who think their own congregations are a bunch of bigots.

Still fuming, I picked up the main road to Great Torrington, which led down a hill and crossed the trackbed of the old line to Bideford, which I joined. It took me to Torrington in a broad loop along the floor of the steep valley of the River Torridge as it tumbled through the woods and ferns. My mood had brightened by the time I reached Torrington’s old station, at the western end of the town. Now serving as a cafe and information centre, it told me that I’d joined the big inland attraction of northwest Devon, the Tarka Trail. It looked like I could use it to Bideford.

But first I needed to get off it briefly to bag Torrington. This was another hilltop place, and it meant the day’s first steep climb and also its first really busy road. At this large, handsome old market town built on wool and farming, I had a splendid pasty at Sandfords, a long-established family-run bakery, before pottering around the streets a bit. A cramped, irregular but lively centre, with a fine Georgian town hall on pillars and a Gothic pinnacle of a market cross, where I placed my foot. Torrington was on the list.

Torrington occupied a strategic point above the Torridge and became a castle town at an early date. The castle was destroyed in the Civil War, when Fairfax took it, ending Royalist resistance in the West Country. Its most notable inhabitant was perhaps Thomas Fowler, a pioneer of radiator-type central heating, which most English people schooled in those bleak Victorian barrack rooms of the 1970s will remember with gratitude. His role in this art is little-known because his patent was so flawed it allowed others to steal and develop his “thermosiphon” idea, and he lacked the resources for legal recourse. Fowler, a fellmonger by trade, seems to have been a true rustic genius. “After a hard day’s work among sheepskins,” his son wrote, “he would spend half the night poring over his mathematics” until he had independently mastered differential calculus. He’s also considered a pioneer of computing.

But what most tourists come to Torrington for is the above-mentioned Tarka Trail, which just goes to show how much mileage you can get out of a fictional otter if you do the marketing right. Henry Williamson’s 1927 creation dominates the large tract between Barnstaple and Okehampton and beyond, giving name to 180 miles of biking and walking trails and even an active railway line. A prolific and painstaking nature writer, Williamson rewrote Tarka 17 times, according to his son Richard. I read it once years ago and I have to confess I can remember nothing whatsoever about it. Weirdly, Williamson died during the death-scene of his otter in a screen version of the story he was overseeing.

The Tarka trail took me all the way to Bideford. Still the old railway trackbed, it continued to follow the Torridge closely, passing the one spot where, a plaque said, there actually were a few, rarely spotted, resident otters. It was a lovely winding, shady ride, with the glint and murmur of flowing water always at hand shifting to the right or left with each little bridge. The Torridge broadened progressively as it approached Bideford, where it left its sheaf of woodland and flowered into a full-sized river, edged by broad pool-pocked mudflats overlaid by carpets of coarse grass. Gulls patrolled the waters and waders picked at the mud; the sea was near now.

Indeed, white-fronted Bideford had a seaside air, and once was in fact a major port, though it’s somewhat inland. Like Berwick, it faces a broad river and is approached by a splendid old arched bridge, which carries you over the Torridge and dumps you onto one of the worst junctions in the county. The town is built on a steep hillside with twisting alleyways running in all directions like the roots of an old oak on a bank. It was hard enough pushing the bike up those slopes; I’d imagine black ice could bring the place to a complete halt. As it was, Bideford wasn’t exactly heaving now, despite its prettiness. I stopped to look over the pannier market, a regular feature of Devon towns (it’s an indoor market where people brought goods to sell in baskets or panniers). But the hall was empty of vendors, except for a solitary old confectioner, and some of the booths looked permanently shut. A sad sight.

I left the rail trail at Bideford and followed a long, rolling lane calling itself the “old Barnstaple road” to its end. A pleasant run, punctuated by frequent stops to pick and scoff blackberries from the abundant hedges — this was a very good year for the only wild fruit in England you can eat with relish and without worry.

Though evening was coming on now, I wasn’t quite ready to stop at Barnstaple, and instead of going into town, rejoined the excellent rail trail heading along the other side of the river to Braunton. This town proved to be the disappointment of the tour. There was nothing there at all really, just a large old airbase, now evidently serving as a Marines centre, commanding a marshy shore. I’ve yet to see an English rural town with a military presence that isn’t a dump.

I took a bus back to Barnstaple in the dusk, where I spent the night in a pre-booked guesthouse. Wandering around the town in the evening, I wondered how I could best express my anti-racist empathy with the small army of swarthy migrants enlivening the streets by riding on the pavements at 30 mph on their souped-up, light-less electric bikes. I settled for leaving a proper tip, for once, after a curry at a Sri Lankan restaurant. The waitress’ English wasn’t great — nor was the curry, for that matter — but my virtue had been signalled. I went to bed and slept the sleep of the morally superior.

Early the following morning, I wandered along the riverbank and up and down the handsome old main streets, which had many buildings of character and historical interest. One of them was St Anne’s Chapel, a small stone chapel in the church cemetery. The door was open, so I got off and had a look.

In fact, it wasn’t open to the public after all; I’d caught a volunteer team doing restoration work. Instead of kicking me out, one of them kindly explained that the building was originally fourteenth century, and had served as a chantry chapel and charnel house before becoming a school from the mid-1600s to mid-1800s. He showed me was what were believed to be little paper planes thrown around by pupils, found lying in the dust of the ceiling rafters. They were formed like butterflies, and tipped by shivers of flint from pens to weight them. I was charmed. How much more evocative were these playthings than old schoolbooks, inkwells and scratched desks.

My informant, a local historian, also had things to say about the tract of Devon I’d just ridden through. There was indeed a lot of “dead” land now, he said, as farmers were pulling out of the beef and dairying businesses. A family in his village outside Barnstaple had just sold up to a construction company, because they had no sons to carry on the farm. There was a lot of “probably necessary” house-building going on across the county, he added, without sounding very enthusiastic about it. (If this was so, I saw very little of it.) Still thriving, he said, was the fruit- and vegetable-growing in coastal areas. Two big customers were the military and cruise ships, for which pallets were delivered to Southampton fresh.

I have to confess I didn’t know what either a chantry chapel or charnel house were. The former were endowed institutions for daily masses for their founders, and the latter a kind of temporary storage area for bones unearthed for one reason or another. Also en route to the station was the shell of an old Telephone Exchange. Remember them? Seeing those words brought back deeply buried memories, of laboriously dialling — not pressing — numbers, asking the operator for help with area codes — dial zero, wasn’t it? — and calling the Speaking Clock. It was jarring to reflect that probably half the British population today have never dialled a phone number.

Barnstaple station served a major junction 50 years ago, but now it’s a small branch-line terminus, buried away at the back of an ugly slew of industrial and retail sheds of the kind that disfigure so many rural towns now. The woman in front of me in the ticketing hall queue was quoted, if I heard correctly, £240 for a single to Norwich. That was more than Moscow to Ulaanbaatar. I was pretty glad I only needed to pay for the stretch down the Tarka line to Exeter, having bought a return from there.

A last thought: if I’d been able to see the flood on the first morning of these rides, I’d have probably turned back, as there was no way round the water. I’d already toyed with the idea of aborting it at my very departure. It was only because I was already thoroughly soaked that I decided to just plough on.

More like this can be found at my website Riding the Shires. Half a century of cycle-touring.

I’m fine with being quoted (up to two paragraphs), but all rights @joeslater.

© text & images Joe Slater 2025