“Necessity is the mother of invention” is a proverb which, though not in those precise words, dates back to at least 6BC, featuring in one of Aesop’s fables (“The Crow and the Pitcher” if you want to explore further).

The guitar emerged, it is thought, in Spain in around 1200 (AD this time), likely as the offspring of the oud and the lute. It became a staple of many types of music, including jazz. As jazz and swing gained in popularity in the 1930’s the bands and venues grew in size, to the point where the guitar was no longer viable as an acoustic instrument.

Early attempts to amplify the guitar sound by sticking a microphone in front of it met with mixed results – often it worked but there was a fundamental problem (which was later to become a “feature” rather than a “bug”, but we’ll get to that). The problem was feedback – when the amplified sound of the guitar string vibrating fed back into the guitar, making the string vibrate more, which then fed back into the guitar until it (quickly) became a howl. We’ve all heard it when people speak into a microphone whilst standing in front of the line of the speakers. For some reason this is nearly always followed by the culprit adopting a puzzled look, taking a step back and then tapping the microphone as though taking part in some kind of arcane folk club indoctrination ritual.

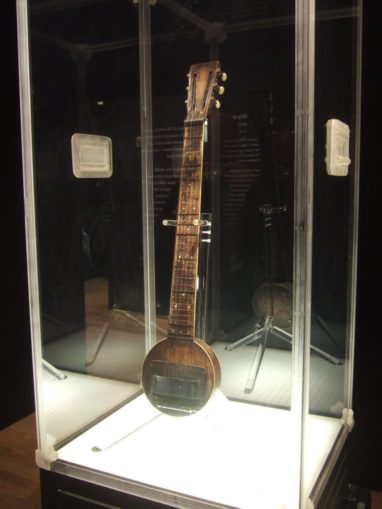

As a side note, another invention to make the guitar louder was to make part or all of the guitar from metal and to place cone-shaped “resonators” (typically of aluminium) inside the body. These resonator guitars lived on in blues and bluegrass music until becoming an icon of the CD era

CC BY 2.0

Let’s get loud(er)

The obvious solution was to somehow get the sound out of the guitar then into an amplifier and speaker without the use of a microphone. Electrical amplification was invented in the early 1920’s and by as early as 1924 an engineer for the Gibson instrument-making company called Lloyd Loar (a fascinating chap who deserves his own article. He signed up in WWI to entertain the Allied troops, shipping out to France from the USA and reporting for duty on 9th November 1918 – pretty good timing really) developed an electrical pickup for the viola. In his design the vibration of the strings was transmitted from the wooden bridge (the bit the strings rest on at the opposite end to the one with the big tuning pegs on it) to make a metal coil pass over a magnet, therby creating a small electric current which could be sent down a cable to an amplifier. This worked, but the signal was quite weak and the amplifiers of the day were quite noisy so the result wasn’t practical at volume.

Given the pace of innovation and invention during the late 1920’s/early 1930’s it isn’t possible to say who first realised that metal strings passing over a magnet would also create a small electric current. Winding thin wire around the magnet (or multiple magnets – one for each string) increased the signal strength to a far more usable level.

Initially the “pickup” (so called because it “picked up” the sound from the string) was popularised as something to be added to a hollow-bodied guitar, with the jazz guitarist Charlie Christian being seen as one of the earliest, if not the first, high-profile adopters of this approach.

English: Published by DownBeat magazine. Photographed by Charles B. Nadell (per this scan)., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Because the pickup was mounted on an acoustic instrument, feedback was still a problem. The obvious solution to this was actually being developed for a different type of guitar – the “lap-steel” guitar, which was played horizontally using a metal slide in the left hand and plucking the strings with the right hand. Think of the music in any scene set on a tropical island in any 1950’s film when a shapely young thing walks into shot wearing a grass skirt and dancing – that’s what it sounds like.

The first lap-steel guitars to use an electric pickup were made of solid metal, cast as a single lump of aluminium, with the Rickenbacker Electro A-22 considered to be the first commercially successful electric guitar (albeit not what most of us think of when we think of the electric guitar). One interesting design feature of this guitar is that the pickups are actually a flat horseshoe shape and they pass over the strings rather than under them, as can be seen in the image below.

wetwebwork, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

While the A-22 went on sale in 1932 it wasn’t patented until 1937, leaving the field open for others to experiment with different designs and products. A number of people started building prototype solid-bodied guitars, with the pickups from the electro-acoustic guitars then available mounted to, surpise, surprise, a solid body. The most well-known of these innovators was an American guitarist called Les Paul, who was a popular recording artist with his wife, Mary Ford.

Paul built a prototype solid-body guitar called “The Log”, from a 4″ by 4″ Douglas Fir fence post. To make it look a bit more normal he cut the body of a hollow-bodied guitar in half lengthways and stuck the two halves on each side of the solid middle. He took this idea to the Gibson Guitar Corporation in 1941 but they weren’t interested (which was very nearly the equivalent of turning down The Beatles). Throughout the 1940s a number of solid body guitars were built and marketed, but none of these had any significant success.

While all of this was going on another all-round clever chap called Leo Fender had patented both a pickup and a lap steel guitar in 1944 and starting selling this as a package with an amplifier which was built by the company he co-founded. This company became the Fender Electrical Instrument Co in 1947 when the other founder dropped out. In 1948 Fender produced a prototype for a thin-bodied guitar, launched in 1950 as the Fender Esquire, with a twin-pickup version being launched in 1951 (originally called the Broadcaster but quickly renamed as the Telecaster after a trademark issue).

Fender’s success caused Gibson to have a quick rethink and they issued the Gibson Les Paul in 1952. With Fender bringing out the three-pickup Stratocaster in 1953 the Holy Trinity of electric guitars (Strat, Tele and Les Paul) was complete, with all three being sold in huge volumes over 70 years later.

To this day the fundamentals of the electric guitar remain the same – metal strings, pickups, a switch to choose different combinations of pickup, volume controls and tone controls to modify the sound of the pickups.

This hasn’t stifled innovation though – off the top of my head and backed up by no research whatsoever, since the earliest days of the electric guitar we have seen:

- the electric bass guitar (fretted and fretless)

- headless guitars (very popular in the 80s – I have one myself, which I have played on stage at the O2 in front of 14,000 people, but that’s a story for another day)

- guitars with up to five necks (fun fact – if you buy a twin-neck guitar with a 12-string and six-string neck you are required by law to play Stairway to Heaven on it at least once)

- a broad range of body shapes (Dave Hill from Slade was particularly well known for his penchant for strange guitars)

- guitars which generate the digital output required to control synthesisers (more on this in another article)

- guitars with synthesisers built in

- guitars made from carbon fibre, cardboard, pencils and even, famously, a mantelpiece (Brian May’s “Red Special”)

Modern guitar amplifiers also produce a wide range of sounds, with recent “modelling” amps being able to replicate the sound of pretty much any amp, speaker and venue mix.

Back in the early days the objective of the amp was to accurately reduce the lovely clean tone of the guitar, but one British chap was instrumental in changing all of that – more on him next time.

© Northern Man 2025