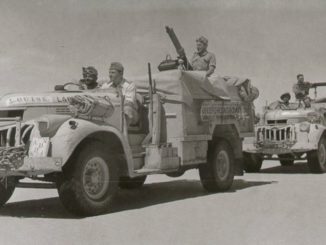

No 1 Army Film & Photographic Unit, Keating G (Capt), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

When you hear the name Fitzroy Maclean, what comes to mind? For many, it’s his role as a founding member of the SAS, those daring desert raiders of World War II. Others might recall his pivotal influence in Yugoslavia, where historians credit him with altering the course of a nation’s history.

But Maclean was more than a soldier or a diplomat. He was a 6-foot-4 polyglot who spoke seven languages, a Member of Parliament for 34 years, an author of 20 books, a BBC producer, and a man who seemed to live 19 lives in one.

If you enjoy tales of adventure, character, and a life well-lived, pull up a chair. This is the story of Fitzroy Maclean, a man who strode through the 20th century in a kilt, with a grin and a glass in hand.

A Noble Lineage and a Wandering Childhood

Fitzroy Maclean’s story begins with a proud Scottish heritage. The Maclean clan, with roots stretching back centuries, carried two mottos: “Thank God I am a Maclean” and “Though poor, I am noble.” The latter certainly applied to Fitzroy’s father, Charles, a World War I veteran who, after being wounded and pensioned off, moved the family to Italy to stretch their modest income.

Fitzroy was born in 1911 in Egypt, but his childhood was a whirlwind of movement, two years in Scotland, two in India, two in England, before settling in Italy at age eight. Even as a boy, he showed a knack for languages, picking up English, French, and Italian with ease.

By 13, he was off to Eton, suited up and ready to make his mark. There, he excelled, winning prizes and, as was the custom of the time, enduring the occasional flogging. Eton led to Cambridge, followed by a year studying in Germany. His mother, spotting his potential, nudged him toward the Diplomatic Service, where his diligence earned him a reputation as “one to watch.” His first posting? Paris, where he was at just the right age to savour the city’s glittering social life.

Moscow and the Soviet Adventures

After three years in Paris, Fitzroy, ever restless, requested a transfer to Moscow. It was the 1930s, and the Soviet Union was a cauldron of intrigue. He quickly mastered Russian, including the patois of the peasants, and spent his leave exploring remote corners of Soviet Central Asia. These clandestine adventures, often in forbidden regions, drew the attention of the KGB who were less than amused.

Fitzroy’s diplomatic credentials landed him a front-row seat at one of Stalin’s infamous show trials where he witnessed the brutal machinery of Soviet justice first hand. Related in his memoir Eastern Approaches his contemporaneous account of the trial is still the most objective ever written.

His time in Moscow wasn’t just about adventure. It sharpened his understanding of geopolitics and human nature, skills that would prove invaluable later. He had limited success in getting to know the leading Soviet officials because they avoided western diplomats like the plague. However through a close friendship with his opposite number in the German embassy, he was able to give advance warning of the likelihood of a Nazi-Soviet pact, events that shaped the prelude to World War II. But as war broke out Fitzroy found himself back in London itching to do more than shuffle papers.

From Diplomat to Desert Rogue

The Diplomatic Service had strict rules against joining the military, but Fitzroy, at 30, found a loophole. If he became an MP he automatically had to leave the diplomatic service. And so he did – he won the 1941 by-election for Lancaster. Churchill joked in Parliament that Fitzroy had used that institution as a “public convenience”.

Immediately after he enlisted as a private in his father’s old regiment, the Cameron Highlanders. There he was surrounded by 19-year-olds from Glasgow’s tough Gorbals district but he settled in to army life better than them due his experience at Eton. “They may have been handy with a razor”, he quipped, “but they were soft really”. His leadership and grit saw him quickly rise to captain, and soon he was posted to Egypt, where he joined the fledgling Special Air Service (SAS).

The SAS was a new kind of unit, small, mobile, and audacious. In the North African desert, Fitzroy thrived. He led hit-and-run raids on Axis fuel dumps, drove Long Range Desert Group jeeps across 500-mile stretches of sand, and struck fear into Rommel’s Afrika Korps. The Benghazi Raid of June 1942 saw him dodge Italian guards to torch vital supplies. In September, his platoon stormed Barce airfield, destroying over 30 Italian planes. These operations weren’t just daring, they disrupted Rommel’s supply lines and communications giving the Allies a critical edge.

But the desert was unforgiving. Fitzroy survived six risky parachute jumps, two close calls in combat, and a jeep accident that landed him in hospital for three months. If a cat has nine lives, Fitzroy burned through nine in the desert alone. His exploits inspired scenes in the TV series Rogue Heroes, though no public photos of him from this time survive. Still, his legend grew.

Persia and the Nazi Plot

In early 1942, Fitzroy was sent to the Persia-Iraq Command, tasked with scouting for a potential Nazi infiltration. The Axis threat loomed large until Stalingrad and El Alamein shifted the tide.

One of his most intrepid assignments was Operation Pongo, a stealth raid to arrest Fazlollah Zahedi, the pro-German governor of Isfahan. Fitzroy and the Seaforth Highlanders swooped in, nabbed Zahedi and flew him to Palestine. Zahedi’s stash of German guns and incriminating correspondence confirmed his Nazi ties. Thus was a dangerous plot averted.

Yugoslavia: Changing History

In 1943, Fitzroy parachuted into Yugoslavia as Churchill’s liaison to the resistance. His mission was to assess the relative merits of the competing anti-Nazi factions, the Partisans, led by Tito, versus the rival Chetniks. Whoever got Fitzroy’s approval would change the course of history – communists versus royalists. The Partisans won his confidence and Fitzroy’s reports to Churchill ensured that the RAF delivered a huge tonnage of food, ammunition, and supplies, bolstering Tito’s forces against the Axis and sidelining the Chetniks.

Life in Yugoslavia was a gauntlet of danger. In May 1944, German paratroops stormed Tito’s headquarters in Drvar, forcing Fitzroy to flee through caves under fire. From the island of Vis, he ran raids, ferried guns, and gathered intelligence. By late 1944, he marched with Tito’s partisans and the Red Army to liberate Belgrade.

Fitzroy’s rock-solid relationship with Tito helped shape Yugoslavia’s post-war path, giving that country’s leader some confidence that it would get western support to help steer it away from Soviet domination.

Fitzroy lost several more of his “lives” in Yugoslavia, but his impact is undeniable.

A Life Beyond the War

You’d think the end of the war would slow Fitzroy down, but he was just getting started. In 1947, he married Veronica Fraser, a 26-year-old war widow with two children. Their marriage produced two more, and Veronica, a formidable figure from a political family, became his partner in every sense. Together, they embarked on exotic travels, from the Caucasus to Central Asia, living life with the same gusto Fitzroy brought to the battlefield.

Back in Britain, Fitzroy served as an MP for 34 years, from 1941 to 1974, representing Lancaster and later Bute. Known for fiercely defending the Army in Parliament, he was a popular and diligent MP, guided by Veronica’s political savvy. He became a stalwart of the British establishment, serving as godfather to Winston Churchill’s granddaughter and chairing numerous committees.

His 1949 book, Eastern Approaches, a memoir of his Soviet and wartime adventures, sold over a million copies and remains in print. He wrote 19 more books, produced BBC travel documentaries, and became a sought-after speaker on the U.S. lecture circuit. Fitzroy’s charm drew him into the orbit of the era’s giants: politicians, royalty, presidents, and even film stars.

In the mid-1960s, he and Veronica bought a house in Yugoslavia, spending two months each year there. He appeared on Desert Island Discs and This Is Your Life, cementing his status as a national treasure. In 1957, the couple purchased the Strachur estate in Scotland, including the Creggans Inn where Fitzroy could often be found chatting with locals or his manager, Jimmy McNab.

At the age of 78 he and Veronica fulfilled a long-standing ambition by travelling by truck and train from Gilgit in Pakistan along the old Silk Route to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan. His 79th birthday found him accompanying Veronica to Nepal and to the Kingdom of Lo, a walled city 12,000 feet up in the Himalayas, reachable only by ladder.

The James Bond Question

Was Fitzroy Maclean the inspiration for James Bond? The question dogged him for years, and he always laughed it off, denying any espionage. But the parallels are hard to ignore. A dashing, multilingual diplomat-turned-soldier with a knack for danger? Ian Fleming, who knew Fitzroy, likely drew some inspiration. Whether or not he was 007’s blueprint, he lived a life that rivalled Bond’s wildest adventures.

A Man of Many Lives

Fitzroy Maclean died in 1996, leaving a legacy that’s hard to sum up. He was tough as old boots, could drink most men under the table, and lived with an infectious zest. From the deserts of North Africa to the mountains of Yugoslavia, from Parliament to the pages of his books, he left his mark. He wasn’t just a soldier, diplomat, or writer, he was a man who seized every opportunity, loved deeply, and laughed often.

For those of us who admire men who live boldly, Fitzroy Maclean is a hero worth remembering. His life reminds us that adventure isn’t just for the young and nobility isn’t about wealth, it’s about character. So here’s to Fitzroy – a Maclean, a wanderer, and a man who changed history one daring step at a time.

© listerman 2025